Involvement in forming and leading the JC Exiles Group in Kansai

Following the official apology in 1988 by the prime minister of Canada to Japanese Canadians, a delegation was sent by the Canadian government to Japan to explain the terms of redress to the Japanese Canadian exiles still living there. These explanation meetings brought together many exiles who had not seen each other since the internment. Tak says that they had some idea of others who had been deported to Japan, but many had lost contact with each other and did not know where in Japan others were located.

When Tatsuo Kage and the Canadian delegation came to Japan to explain to us regarding the redress compensation program, they first came to Tokyo and contacted Japanese Canadians there. There were probably some Japanese Canadians back in Canada who knew Japanese Canadians in Japan and provided the contact information.

Anyway, this led to word getting around that there would be an explanation meeting and all those interested should attend (ads were placed in newspapers as well). At the meeting, many ran into old friends, some of whom they thought weren’t even in Japan, and for future liaison, they probably figured they should form some sort of organization. I can’t recall how it came about exactly, but there were a number of ex-Lemon Creekers in Tokyo whom I knew and one of them was a classmate from Vancouver days.

One chap, Kaz Ide, who was my younger brother Gabby’s pal in Lemon Creek days, was very active in the organization and I think he was the first president. There was another ex-Lemon Creeker, named Lloyd Kumagai, also in Tokyo, and they both contacted us in the Kansai region and invited us to join the association. At that time, we were still waiting for more redress information and application papers, and things were being organized so more people could be more expeditiously contacted. The original organization had a membership of about 70 or 80 persons from all over Japan.

Eventually Tak and some other exiles living in the Kansai region banded together and formed a small Kansai branch, in which Tak played a leading role. He explains about its formation and the relationships of some of the leading members as follows:

We formed a Kansai chapter (about 20 members), and Tom Mizuguchi and I, together with another chap, Kiyoshi Muraki (now deceased), used to go to Tokyo to attend the meetings twice a year in the spring and autumn. We were sort of self-appointed directors. Later I had to resign due to my business commitments requiring many overseas trips which resulted in my absence from Japan when the meetings were held.

The Tokyo and Kansai groups continued as social groups after redress. Tom and I, as sort of caretakers, tried to keep the Kansai group going. We would arrange for the meeting place and would send out notices to all the members. We used to get together at hotel restaurants in Osaka and, in the later years, we used the Kobe Club quite a bit. Fuji Fujino was a member of the Kobe Club, so we could take advantage of her membership privileges. I tried to keep the group together by writing a sort of circular letter addressed to all who attended our luncheons. Later, as we got older, some could not attend, others passed away and the organization went out of existence.

I believe that Fujino-san and Hosoi-san, who were both important members and were my seniors, had been stranded in Japan when the war started. They had been brought here by their parents and the war started before they could return. My recollection is that I was introduced to Fujino-san at the now defunct Osaka Grand Hotel by a mutual friend. It turned out that her older brother, Abe Korenaga, was an Asahi baseball star and of course as a kid I had been his fan.

There were a lot of Lemon Creekers so I knew most of them and had helped put the Kansai group together but had to resign my responsibilities due to my job requiring frequent overseas trips and I was starting to miss meetings. However, I continued to be a member.

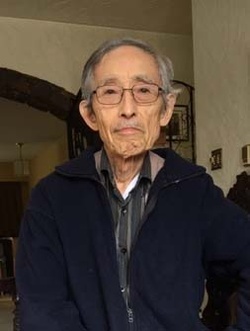

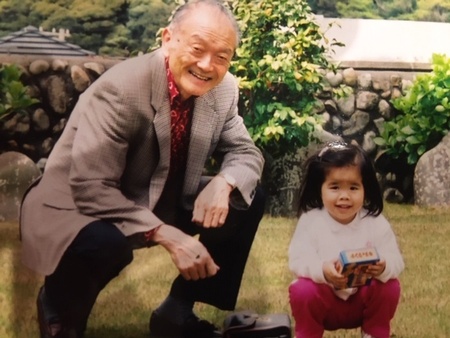

Life after Retirement and Thoughts about Canada

Tak has kept active ever since his retirement from Fujicopian, and has made several travels with his wife. She unexpectedly passed away due to complications resulting from the treatment of esophageal cancer in 2015. Now, in his early nineties, Tak still tries to stay socially active, but confesses that recently he has been feeling like he is slowing down. He especially feels socially hindered by his loss of hearing in recent years. At present he lives in Nishinomiya, a suburb of Osaka. He has three daughters, all of whom are married to Japanese nationals, and six grandchildren.

Reflecting on his internment and exile from Canada, Tak says he does not feel any bitterness towards Canada now, although his indignation sometimes surfaces when talking about the experience of being exiled. He vividly recalls attending the meeting held by a Canadian government delegation explaining that he, along with other Japanese Canadian exiles, was eligible for redress, and the subsequent process of filling out the required forms and showing proof of citizenship. He believes in putting the past behind and looking ahead, but he hopes that young Japanese Canadians will remember what happened to their community and “will work to ensure that something like that will never happen again, not only to Japanese Canadians, but to other minorities in Canada as well.”1

He still has Canadian citizenship (living in Japan under a permanent residency visa) and hence feels that he is a Canadian “because of my birthright”. He thinks he might have wished to return to Canada during the first few difficult years in Japan, but after ten or so years had passed, he came to feel quite comfortable in Japan. He says he doesn’t think he will ever feel completely Japanese, but on the other hand, thinks he would find it very difficult to ever feel completely Canadian, partly because of his lack of contact with Canadian society even while a child and teenager in Canada.

All those years we were in Lemon Creek camp, I was isolated from Canadian society, so I hardly knew what a truly Canadian society was when I was growing up, and I became an adult after I got to Japan, so it’s difficult to say. However, I guess I have to say I feel more Canadian than Japanese because when I’m thinking, I’m thinking in English. My wife used to tell me I talk in my sleep in English.2

This ambiguous sense of national identity was also reflected in an interview with Norm Ibuki in 2014 when he noted, “When forced to live in a ‘foreign country,’ the language, customs, food, etc. can make things unbelievably difficult. Even for second generation Nikkei with the advantage of racial origin, the conditions in Japan were so severe that I think many could never adapt. Although I have lived in Japan for so long, at times I get the feeling that I am not completely used to the country.”3

Notes:

1.Norm Masaji Ibuki in “Tak Matsuba’s Odyssey from Vancouver to Osaka - Part 2,” Discover Nikkei, May 20, 2014.

2.In Japanese-Canadian Stories from Japan: compiled by Nobuko Nakayama and Jean Maeda. Tokyo, 2011, p. 29.

3. Ibuki, Ibid, May 20, 2014.

* This series is an abridged version of a paper titled, “A Japanese Canadian Teenage Exile: The Life History of Takeshi (Tak) Matsuba,” published in Language and Culture: The Journal of the Institute for Language and Culture, Konan University, March 2020.

© 2020 Stanley Kirk