Arrival in Vancouver

At some point in the mid-1950s, Hyoshiro and Fujiye Hirai decided to move their family back to Canada. Miki now characterizes his life after returning to Canada as “a story of frustration, challenge and finding success in my own way. It has been a long time, starting in 1956, and is still going on.”

He describes why his family returned to Canada as follows: On his mother Fujiye’s side, two of her brothers and one sister were living in Taber (in southern Alberta), while just one sister was living in Oyabu, their hometown in Shiga prefecture. Hyoshiro and Fujiye had good relations with her side of the family, and Miki speculates that they wanted to be together with them. Perhaps they also felt their family would have a better economic future in Canada. Miki notes, “In Japan, our family just survived and we had nothing to show for a total of about eleven years.”

Shig returned to Canada first in 1954 at the age of 16, sponsored by his maternal uncle. Because he was nine when he had left Canada for Japan, English was not a problem for him after returning to Canada. At first, he lived on a sugar beet farm near Taber (in southern Alberta) with his uncle who had sponsored him. As his uncle was a bachelor, Shig had to look after the cooking using a wood-burning stove. The menu was mostly limited to canned foods and bread.

He strongly wished to go to high school in Canada, but his uncle told him this was impossible as they needed to save money in order to sponsor the rest of his family to Canada. Hence, instead of studying, he found himself laboring long hours during the summer on the sugar beet farm, often from about six o’clock in the morning till about ten in the evening, and in the winter he worked at a sawmill at Williams Lake, BC. He was never able to realize his wish to go to high school in Canada.

According to Shig’s wife Akemi, due to his good speaking skill in Japanese and his enjoyment at communicating with older people, he became quite popular among elderly Japanese Canadians. She recalls:

I heard that there were old people who could talk in Japanese and a few of them called Shig “Japan Boy!!” and wanted to have conversations with him and ask him how Japan was…they had him do extra work and told him to stay for dinner and talk more…they were happy to have him come…Maybe that’s why Shig became a talker…he enjoyed talking with many older people!

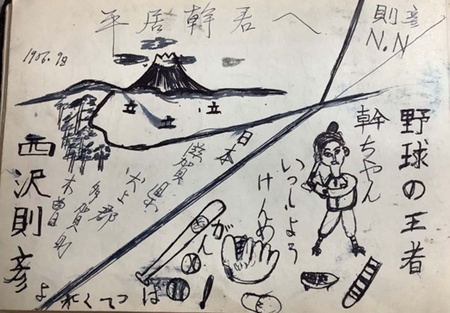

In late February of 1956, Miki and his mother, sponsored by their uncle and Shig, returned to Canada from Japan. Miki was still eleven years old and in grade five at Taga Elementary School. A week before his departure, he asked his baseball friends in Taga to write something for him, so they each wrote a farewell note in an autograph booklet. He has kept it ever since and showed it to them many years later when he visited Japan, much to their surprise. They told him that he is the only one of them who still has anything like that from their childhood.

They sailed to Canada on the Hikama Maru, arriving in March. Miki was seasick during most of the ten-day voyage. They stopped at Hawaii first, and then Seattle, and finally Vancouver. While walking in a Seattle fish market, Miki was surprised at the size of some crabs he saw — much larger than the crabs he had seen in Japan. A lady who had been a passenger on the same boat noticed his amazement and bought one for him to eat.1

Miki vividly remembers seeing the Hotel Vancouver and the Marine Building when they landed. Mrs. Kada, a friend of his mother, met them and they stayed with the Kada family during their short stay in Vancouver. Miki used to watch Western movies in Japan and really wanted a toy pistol, which Mrs. Kada bought him, much to his excitement.

During his stay in Vancouver, he also experienced his first taste of Coke. At first it seemed a little bitter, but now is his favorite drink. He also recalls meeting other family friends. He was surprised to see houses with central heating, gas stoves, refrigerators, and hot water coming out of a tap. These modern conveniences were unimaginable in postwar Japan.2

Life in Alberta

Shortly after their return to Canada, Fujiye and Miki moved to a large sugar beet farm near Taber, Alberta, near where her sisters who had stayed in Canada after the war were living. Miki explains, “My first experience of Canadian life was at Taber.”

The farm was owned by a Mormon family. As part of their contract, they were provided with a small one-floor bungalow. The nearest town, Taber, was twenty-five minutes away by car. Both the geographical surroundings and the way of life there were a big surprise to Miki. “In Taber, the first thing we saw was the massive land, as far as you could see, 360 degrees, no matter where you looked.” He was amazed to be able to see the sun rise from the eastern horizon and set on the western horizon.3 Miki recalls:

So, we got to the house. It was a small bungalow, one floor, with two or three bedrooms, and a kitchen in the middle, and an outhouse about a hundred meters away. There was no electricity and no water. Even in Japan after the war we’d had electricity. There we’d had a radio, but here we had nothing. There was just a kerosene lamp in the house.

It reminded Miki of the cowboy movies he used to watch in Japan.

Although treated well, the Hirai family was very isolated. The boss’s house was about five hundred meters away, and the nearest neighbor lived five miles away. The post office was about twenty miles away. They didn’t have a car so couldn’t go anywhere and had to wait for a bus to go to town. When they wanted to go shopping, they had to ask a neighbor for a ride to town. “We had no telephone, and just felt cut off from everything. It was so quiet, but you could hear the coyotes at night.”

The next chapter will be about the process of adjusting to life in Canada.

Notes:

1. Nikkei National Museum and Cultural Centre (2023, September 23) Okaeri-Miki Hirai [YouTube].

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid.

© 2024 Stanley Kirk