A rather unsuspected but significant force in Japanese American life has been the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (whose members are commonly known as Latter-day Saints or Mormons—the latter name derives from the Book of Mormon, the Church’s key scriptural text).

Throughout the first half of the 20th century, LDS congregations and missionaries interacted with Japanese communities in different locations, even as thousands of Japanese Americans subjected to official confinement in Utah and Idaho during World War II came into close contact with LDS church members. While relatively few Japanese Americans took up the faith during this period, Nisei Mormons ultimately played a disproportionate part in shaping Japanese communities.

To begin with, the LDS church conducted missionary work in Japan, through which it encountered Japanese people. The first Japanese mission opened in 1901. Among the group of pioneering missionaries was Heber J. Grant, who was later to serve as president of the LDS church during WWII. The mission closed in 1924, a casualty of growing Japanese nationalism, anti-American sentiment, and lack of interest by Japanese. By that time, there were approximately 176 members of the church in Japan.

Meanwhile, as they came to North America in the early 1900s, Japanese immigrants came into contact with Mormons. First, a handful of Mormons baptized in Japan settled in the United States. Takeo Fujiwara, who had been baptized by missionaries in his native Hokkaido, Japan, accompanied a missionary returning to Utah, and enrolled at the Brigham Young High School and then Brigham Young University, becoming in 1934 the first Japanese to graduate BYU. After graduation, Fujiwara returned to Japan to direct missionary efforts. Sadly, he soon contracted tuberculosis, and he died barely one year later.

Tsuneko Ishida Nachie, who had worked for 18 years as cook and housekeeper at the residence of the LDS mission president in Japan and had joined the church there, travelled to Hawaii in 1923 to see the temple there, and began work proselytizing other Japanese. She remained in Hawaii until her death in the late 1930s.

Meanwhile, numerous Japanese laborers settled in historic Mormon strongholds in Idaho and Utah. For example, according to historian Eric Walz, Japanese laborers came to Sugar City, near Rexburg, Idaho, to work for the Utah and Idaho Sugar Company, of which the Mormon Church was a principal owner. A handful of Issei accepted baptism.

For example, Tomizo Katsunuma, who came to the United States in 1889 and settled in Logan, Utah, where he studied veterinary medicine, entered the church in 1895 (and simultaneously was able to naturalize as a US citizen). Katsunuma moved to Hawaii soon after and became a Japanese community leader, immigration inspector and columnist for the Nippu Jiji newspaper.

Still, the largest number of the immigrants declined to adopt their neighbors’ religion. This refusal may have been as much cultural as theological. While Issei Christians generally set up their own congregations with Japanese-speaking ministers, no separate Japanese Mormon churches were established on the mainland—it is not clear whether this was mostly due to lack of sufficient Nikkei membership or to principled opposition to ethnic congregations among church leaders.

Nonetheless, there was significant interaction between the newcomers and their Mormon neighbors during the prewar generation. Issei in Rexburg used Mormon churches for meetings of the local Japanese Association. Even unaffiliated Issei parents sent their Nisei children to the local Primary Association (a kind of Mormon version of church school). Walz notes that the register of the Honeyville, Utah Primary lists attendance by Nisei at different times beginning in 1927. In 1941 two Nisei children are listed as having donated 13 cents to the Primary Children’s Hospital (a medical center operated by the LDS church). Mike Ota was invited to speak to the Ogden, Utah branch of Junior Christian Endeavor in 1937 on « Mormonism as I see it. »

Outside of the intermountain West, there was more sporadic contact between Nikkei and Mormons, During the 1930s, the Church Division of Sacramento’s Twilight League featured the Mormon Templars, a club representing the local Latter Day Saints Church.

Some Nisei converted as a result of attending Primaries with their Mormon friends. In 1930, thirteen year-old Wuta Terazara of Sugar City wrote in Nichi Bei Shimbun about the fun of attending cooking demonstrations and going on hikes with her friends at the Primary, and added, “I’m a Mormon and I’m proud to be one too.”

Some years later, Frank and Ralph Nishiguchi secured their father’s consent to be baptized. Kenji Shiozawa, a teenager in Pocatello, Idaho in the 1930s, served as Boy Scout leader, and was later elected president of the Japanese Missionary Re-Union Association, comprised of returned LDS missionaries who had served in Japan and Hawaii. Hiroshi Yasukochi, a Nisei Mormon from Murray, Utah, starred on the Salt Lake Nippons baseball team and contributed articles to the West Coast Nisei press.

In Hawaii, where the LDS Church became renowned for its missionary efforts among native Hawaiians, efforts at winning Japanese converts were less concentrated, though there were a handful of Nikkei church members, including Tomizo Katsunuma, as mentioned, and Tokujiro Sato, a Japanese laborer.

In 1934, the Kalihi (Honolulu) LDS church opened a Japanese school. Three years later, Church officials created a Japanese mission under the direction of Elder Hilton A. Robertson, with 42 missionaries serving in the various islands. (The Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints [today known as the Community of Christ] a separate LDS Church group, had already opened a Japanese Branch in Kalihi in 1929).

When Dr. John Widtsoe, a noted scientist and Mormon leader, arrived in Honolulu in 1938 on a monthlong visit to review Church work in Hawaii, he was escorted by Kay Kichitaro Ikegami, manager of the Japanese department of the State Building & Loan Association, who was listed as a local Japanese Mormon leader. In terms of converts, the Hawaii LDS mission proved to be much more fruitful than the 1901-1924 mission in Japan.

By the end of 1942, there were around 300 Nikkei members of the church (mostly US-born) in Hawaii. Some of those converted during this time went on to become influential church leaders, including Chieko Okazaki, who became a counselor in the Relief Society General Presidency in 1990.

The most significant connections between the LDS Church and the Nikkei were forged by Dr. Elbert Thomas. In 1907, six years after the LDS Church established its first mission in Japan, Thomas and his wife moved to Japan as Mormon missionaries. Once in Japan, Thomas learned to speak and read Japanese language so well that in 1911 he wrote a book in Japanese, Sukai no Michi. Thomas and his wife named their daughter, born in Japan, Chiyo.

The Thomases left Japan in the early 1920s (before the mission finally closed in 1924). After returning to the US, Dr. Thomas served as professor of international law and politics at the University of Utah. He served as a mentor to numerous Nikkei students at Utah, not only because of his command of Japanese language but his attachment to Japan and its culture. In 1934, he was elected to the U.S. Senate as a liberal Democrat.

One of Thomas’s main protégés was Mike Masaru Masaoka. Masaoka, a colorful and controversial figure, was the most famous Nikkei Mormon. However, he clearly separated his religious faith from his public life, and did not generally speak publicly about his religion.

Born in Fresno, Masaoka moved with his family to Salt Lake City as a child. His father died when he was just nine years old, and he was taken up afterwards by white sponsors. Sometime during his childhood, Masaoka was baptized as a Mormon, and joined a Mormon Boy Scout troup. He attended University of Utah, where he distinguished himself as a varsity debater and staffer on the campus newspaper. After graduation, he returned to coach the university debating squad, as well as working in the civic field. He was described in newspaper stories of the time as a “priest” in the Mormon church.

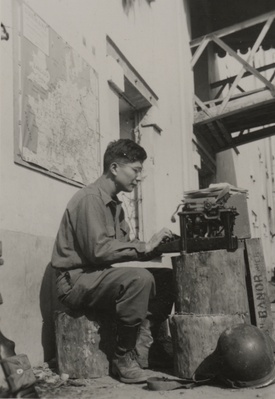

In 1940, at age 24, Masaoka became director of the Utah Conference of Human Relations, an interracial committee. Meanwhile, he served as English editor of the Utah Nippo and became active in the Japanese American Citizens League--as we will see, Masaoka’s actions in founding new chapters later bore fruit for the organization). For the JACL’s biannual convention in 1940, Masaoka penned the “Japanese American Creed,” a manifesto that would guide the organization in future years.

Throughout this period, Masaoka retained a close relationship with Elbert Thomas. While in college, he volunteered for work on Thomas’s successful senate campaign. Thomas offered support and political contacts to the young Masaoka, which were an invaluable aid for in his rise to leadership in the JACL. Notably, as a member of the Senate Education and Labor Committee, Senator Thomas invited Masaoka to a hearing held by the Presidential Commission on Equal Employment Opportunities in Los Angeles in fall 1941, which provided him his first nationwide exposure.

© 2018 Greg Robinson; Christian Heimburger