Grand niece of Farewell to Manzanar author has ‘dream job’ at Minidoka site.

The Wakatsuki name is inextricably linked with the World War II incarceration of Japanese Americans.

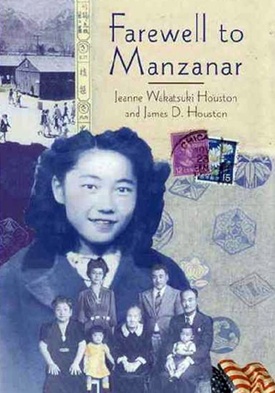

In her 1973 memoir, Farewell to Manzanar, co-written with her husband James, Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston recounts her family’s life on Terminal Island and how it came to an abrupt end with the attack on Pearl Harbor. Her Issei father, Ko, was immediately arrested by the FBI and the rest of the family was incarcerated at Manzanar.

The book and the 1976 TV movie of the same name have been distributed to schools and libraries throughout California and beyond, educating generations of students.

Another of the War Relocation Authority camps was Minidoka in Idaho, where many Japanese Americans from the Pacific Northwest were held. The chief of interpretation and education at Minidoka National Historic Site is Hanako Wakatsuki.

“She is my great aunt on my paternal side, youngest sister of my grandfather,” Wakatsuki said of the author.

One of the many cover illustrations for Farewell to Manzanar over the years features Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston as a young girl and a family photo with Hanako Wakatsuki’s grandparents, Chizu and Woody; great-grandmother, Riku; aunt, Patty; great-great-grandmother, Sugai; great-grandfather, Ko; and uncle, George.

Family History

“My grandfather passed before I was born and my grandmother did not talk about it at all,” Wakatsuki said of her immediate family’s wartime experience. “There was some definite PTSD there. I remember asking her about camp in high school and she would deflect and talk about her childhood instead. At first, I thought that she was going senile, but as I got older and understood the psychological impact that this had on the community, I realized that she was still traumatized by it and did not want to talk about it.

“What I can gather is that my grandfather stepped in as head of household after my great-grandfather was taken by the FBI. My grandparents were a young couple with an infant daughter, my aunt Patty, and that was a lot to assume when you were in your mid-20s. My grandfather managed to keep most of the family intact and registered most of my extended family under one household. My great aunts, who were married, registered under their husband’s family.

“My grandmother ended up giving birth to three children in camp: my uncle George, uncle Woody, and aunt JoAnn … My grandfather wanted to prove loyalty by enlisting into the segregated unit of the Army, but my great-grandfather asked him to wait until he gets drafted, so he did. When my grandfather was drafted, he essentially left my grandmother to be a single mother of four imprisoned. I am sure that took a toll on my grandmother.

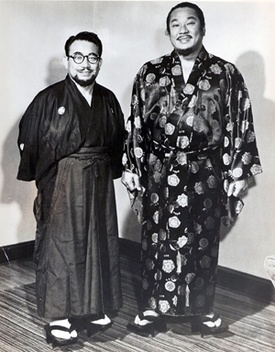

“My grandfather was first assigned to the 522nd Field Artillery Battalion and he trained at Fort Knox. He was then pulled to the Military Intelligence Service and served in Japan. After his service, he came back to California and could not find a job as a returning veteran due to the anti-Japanese sentiment that still existed. My grandfather tried to be a door-to-door salesman, but people did not want to buy from a JA. He ended up becoming a Nisei wrestler because white wrestlers needed an enemy to fight.”

Wakatsuki’s father was the family’s first baby born after camp.

Born in the Bay Area, Wakatsuki moved to Boise as a child, was raised in West Boise and went through primary and secondary schools there. “I was usually the only Asian in my class,” she recalled. “There was another Asian American in my grade that I remember.”

From Manzanar to Minidoka

As long as she can remember, Wakatsuki has been aware of the camps. “Growing up, it was part of our coming-of-age journey to read Farewell to Manzanar in my immediate family. Also, when we were living in California, the movie would come on once a year on TV and we would watch it as a family. So I knew about my family’s history, but we never learned about in school, so I assumed it was some obscure thing that did not impact many people.

“I did not think much of this history until I went to college [Boise State University]. While in college, I was introduced to Minidoka by a retired faculty member, Dr. Bob Sims. I was appalled to learn that Idaho had an incarceration site and we never learned about it in school. That was when I started to re-engage with the JA incarceration history and started to actually understand the impact that it had on the JA and local communities.

“I began focusing my energy to the preservation of Minidoka in college, even though my immediate family was not incarcerated there. Living in Idaho, I did not have much contact with my Aunt Jeanne. But when I began working with Bob Sims, I was able to spend more time with her through events that we invited her to and by traveling with her. I try to visit her [in Santa Cruz]when I can and call her to catch up.”

Wakatsuki earned bachelor’s degrees in history and political science with a minor in Japanese studies, with the goal of becoming a high school history teacher. Eventually she decided that teaching was not for her and planned to pursue a graduate degree in library sciences, even though that wasn’t her passion.

“I didn’t think about being a historian or even think that there was a field for historic preservation or public history,” she said. “I did the minor because as a yon/gosei in Idaho I did not have outlets to explore my cultural heritage. I did not learn about the JACL until college or that Boise had a chapter. So that minor helped me to try and connect with my heritage while living in a ‘whitopia’ that essentially told me that I should reject my culture and assimilate into white America …

“I was guided to the museum field by a classmate of mine who told me to give one last internship a chance … I interned at the Idaho State Historical Museum and loved it! That is where I learned more about public history and wanted to go into this field. I worked for the Historical Museum for about a year and moved over to the Old Idaho Penitentiary State Historic Site for about four years doing interpretive work.

“I decided to get a master’s degree in museum studies at Johns Hopkins University to continue my career in public history. I think that being trained in the field of history and political science helped me with interpreting the complex nature of the Japanese American incarceration during World War II.

“I am able to identify the government policies that led to incarceration and the civil-liberty violations that the JA community had to endure. I have done research to look at the pan-American incarceration of people of Japanese ancestry in the U.S., Canada, and Latin America … I am learning more about the Japanese Australian incarceration that occurred.

“My background allows me to look at things in both historical context and from an administrative view to accurately tell this history by dismantling the old-school narrative that this was somehow justified … The great challenge working in the public history field is to make this information accessible to the general visitor by bridging the gap between academia and the public, but that is the best part of being in this field.”

Working for the NPS

Wakatsuki joined the National Park Service in September 2013, and the timing was unfortunate. Due to an impasse between the Republican-controlled House and the Democrat-controlled Senate, the federal government shut down from Oct. 1 to 17.

As the management assistant for the Tule Lake Unit of WWII Valor in the Pacific National Monument, “I was only able to work five days and ended up driving back home for the remainder of the shutdown, discouraged. My superintendent encouraged me not to give up on my career in the Park Service and was super supportive of me in my endeavors.

“I worked for Tule Lake for a little over a year and took a job with the U.S. Navy Seabee Museum in Southern California [Port Hueneme] as the education specialist to gain my permanent status in the federal service. NPS is a sought-after agency to work at, so it is hard to get a permanent job. After talking to friends and peers at NPS, I figured that I needed a creative strategy to be able to climb the federal ladder and position myself for my dream job, to be chief of interpretation at Minidoka National Historic Site. So that is why I switched departments.

“It worked in my favor … I was recruited for this position at Minidoka when my predecessor decided to retire, because I now had the experience and credentials needed for this job. I honestly did not think that I would get my dream job so early in my career …

“No one ever makes it in life by themselves. I was lucky enough to have people looking out for me and providing sound guidance. I have been the chief of interpretation at Minidoka for a little over a year. So my NPS career is relatively short, only about 2.5 years.”

Wakatsuki’s affiliation with Minidoka includes nine years with Friends of Minidoka, during which she wrote grants to support or develop the site. She spearheaded or worked on such projects as the historic recreation of the Honor Roll (which recognizes the young men and women from the camp who served in the military) and of the guard tower, as well as the annual Minidoka Civil Liberties Symposium.

Friends of Minidoka just republished “Minidoka Interlude,” which is based on the camp’s 1943 school yearbook. Also in the works is “Minidoka National Historic Site,” a book coming out in August through Arcadia Publishing as part of the “Images of America” series.

“Since becoming chief of interpretation, I opened up a temporary visitor contact station at the site in the historic Herrmann House to have site presence for visitors for the first time,” Wakatsuki said. “We are working with our constituents on a variety of projects like … the annual pilgrimage. We are under construction to rehabilitate the historic warehouse on-site to become the permanent visitor contact station, which should be completed by summer of 2019.

“We are working on exhibits and an orientation film for the new visitor center, working on wayfinding signage from the freeway and highways, and have been continuing our educational programming and outreach to the community.”

A Unique Camp

While Tule Lake became a “segregation center” that was run like a maximum-security prison, Minidoka had a reputation of being one of the “better” camps, according to Wakatsuki.

“It was because the incarcerees had a decent relationship with the administration,” she explained. “At first when incarcerees were arriving at Minidoka, there were no guard towers or fence line. A few months later, the guard towers and fence line was constructed and the incarcerees were upset because they never tried to escape … There was nowhere to go and they were living without a fence line for months without incident.

“Also, they were perturbed by the constant reminder of being imprisoned. There was an incident where a portion of the fence line was electrified by the contractors who built it. The project administrator, Harry Stafford, pulled down most of the fence line … and decided to use the guard towers as fire lookouts instead of their intended purpose.

“Another unique thing is that Minidoka was 33,000 acres and one of three Bureau of Reclamation sites and used JA laborers to help prepare the land for the Homestead Act, where returning white veterans from World War II could receive parcels of land through a lottery.”

Pilgrimage Circuit

A self-described “pilgrimage junkie,” Wakatsuki has attended the Minidoka Pilgrimage for the last 11 years and participates in pilgrimages to other camps, including Poston, Ariz. earlier this month and Manzanar this past weekend (April 28-29). This year, there are seven pilgrimages on her itinerary, and she may add Topaz, Utah to the list.

“I love attending pilgrimages because I get to meet lifelong friends and get to enjoy the emotional highs of being part of a community,” she said. “Since I did not grow up within a JA community, nor is there a large JA community where I currently live, the pilgrimages allows me to explore my identity as a JA yon/gosei and connect with the community. It also allows me to better understand the hardships of the experience by talking with our Nisei and Sansei elders.

“All my immediate family that were incarcerated — aunts, uncles, grandparents — has passed and they did not really share their story with me, so this allows me the opportunity to grow closer to them since they are no longer here …

“There is a small group of us that regularly attends the pilgrimage circuit. It is fun to always find a familiar face in the crowd no matter if it is in the high desert of Idaho or the swamps of Arkansas. Amache [Colo.] is the last of the 10 WRA camps that I need to visit. By the end the June, I will have been to all 10 WRA camps within eight months.”

One of her most memorable experience was at the 2014 Tule Lake Pilgrimage, where she hung out with Minnijean Brown Trickey. “I did not know who she was at the time, other than she was smoking on a non-smoking campus … She would have a cigarette and we would just talk about my career goals and life. She was so down-to-earth and told me that I was doing an amazing job to help continue to tell the story of the injustices that occurred at Tule Lake.

“It wasn’t until the last day that someone pointed her out and told me that she was one of the Little Rock Nine that desegregated Central High School [in 1957]. I was floored. I still cherish this memory of just chilling and talking with this amazing woman who kicked down a wall of oppression for all Americans, especially people of color.”

For more information on Minidoka National Historic Site, write to P.O. Box 570, 221 N. State St., Hagerman, ID 83332; call (208) 539-3416; or go online to www.nps.gov/miin The Minidoka Pilgrimage will be held from July 5 to 8. For more information, visit www.minidokapilgrimage.org.

*This article was originally published in The Rafu Shimpo on May 2, 2018.

© 2018 J.K. Yamamoto / Rafu Shimpo