Nikkei Hall sold, proceeds used for community grants.

The Santa Monica Nikkei Hall, once the hub of Santa Monica’s Japanese American community, has been sold by its three remaining officers.

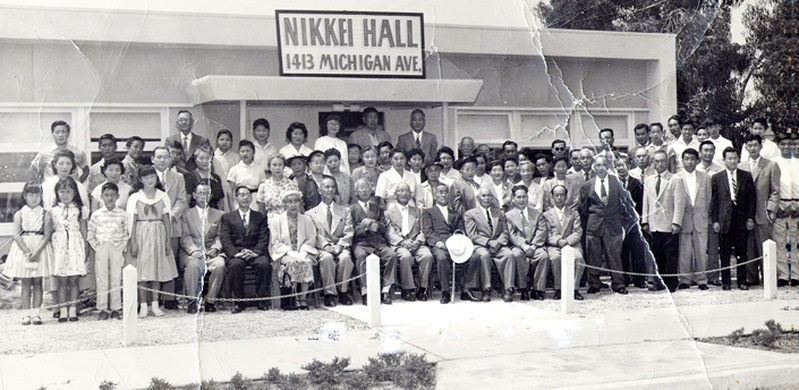

Located at 1413 Michigan Ave., the one-story building was designed in 1957 by architect Y. Tom Makino (1907-1992) and constructed by Santa Monica Nikkei Hall Inc., which was established by Issei community leaders after Japanese Americans returned from the World War II camps.

The buyer is a major television and film production company already located in Santa Monica.

The sellers did not attach any conditions about preservation of the building, but asked the new owner to place a plaque with a photograph of the hall and the following text:

“This property is the former site of Santa Monica Nikkei Hall, a Japanese community organization founded in 1950."

“Proceeds from the 2017 sale of the property were donated to local community and religious organizations, who are now entrusted to preserve and maintain the Ireito on behalf of Santa Monica Nikkei Hall. “

"The Ireito, a 15-foot-high granite memorial monument located in Woodlawn Cemetery, was originally erected to honor the first-generation Japanese (Isseis) who settled in the Bay Cities region of Southern California. The monument has now come to represent all generations of Japanese Americans, including those who served in the United States military. An annual memorial service is held at the Ireito.”

The 59th annual bilingual interfaith service will be held on Monday, May 28, at 9 a.m. at Woodlawn Cemetery on the corner of 14th Street and Pico Boulevard in Santa Monica. Six of the participating organizations are recipients of Santa Monica Nikkei Hall grants: West Los Angeles Holiness Church, West Los Angeles Buddhist Temple, West Los Angeles United Methodist Church, Venice Free Methodist Church, Venice Hongwanji Buddhist Temple, and Venice Japanese Community Center.

Future grants will be made on an annual basis to other organizations supporting the community, with the Los Angeles-based Asian Pacific Community Fund serving as administrator of the fund.

Historical Background

A study submitted to Santa Monica Senior Planner Steve Mizokami by Christine Lazzaretto and Molly Iker-Johnson of HRG regarding the hall’s importance as a historic resource gave the following background:

The Nikkei population enjoyed a higher level of integration and experienced less racial intolerance than other minorities in Santa Monica prior to World War II. Instead of being relegated to the Pico neighborhood, they lived throughout the center part of the city and Ocean Park, and attended public schools.

Katsuzo Matsumura began a Japanese language school (Gakuen) in his living room in 1924 with eight students. As more students began to attend, a school was constructed at 1824 16th St. It also served as a community center, bringing together families for such events as Obon festivals, picnics, parties, plays, and reading and writing contests.

After Pearl Harbor, many local Nikkei were sent to Manzanar. Upon their release, few returned to Santa Monica — about 161 by 1946. They faced a severe housing shortage as the city’s population had increased by about 25 percent from 1940 to 1945. The War Relocation Authority and Federal Public Housing Authority established government-funded housing in converted Army barracks on Pico between 24th and 25th streets as well as in two hostels, while the Gakuen — which had been used as a military training headquarters during the war — became a housing facility.

By 1950, Santa Monica’s Nikkei population had grown to 254. With the immediate postwar problems of resettlement and readjustment no longer as acute, they were able to focus on rebuilding and unifying the community. The newly formed Santa Monica Nikkei Hall Inc. purchased the Michigan Avenue property.

Due to the Alien Land Laws, which were still in force, the property was placed in the names of four Nisei officers: Tetsu Ando, Kozuko Asao, Masaru Matsumura and Jimmy Fukuhara. The group began to collect money from the community while meeting informally at members’ homes for six more years. It was decided to build a new community center because upgrading the Gakuen, which wasn’t up to code, would be too costly.

The directors initially planned to include a barbershop, beauty shop and dry cleaner in the center, but this was later deemed too ambitious.

By 1960, many Nikkei lived in the center portion of the city, settling near the former Gakuen. The most populous streets included Michigan and Delaware avenues and 12th, 18th and 19th streets. Located around the corner from the Gakuen, the hall was a convenient meeting place. At its inception the Nikkei Jin Kai boasted between 75 and 100 members, primarily Issei and Nisei couples.

In 1965, the community began to commemorate Japanese American history, reuniting at the hall annually to honor their predecessors. As time wore on, younger generations assimilated further into American society, and by 2000, the hall was primarily a center for senior citizens with approximately 80 members.

The study concluded, “The potential significance of the property’s historic association with the Japanese American community warrants additional investigation.”

The property also includes a two-bedroom apartment, which would not be considered part of any proposed historical landmark. The unit, which is still occupied, may be a challenge for the new owner because the city has rent control.

Looking Back

During a recent visit to The Rafu Shimpo, the three remaining members — Jimmy Fukuhara, Yutaka Jack Ohigashi and Kazuko Sue Takahashi — shared their memories of Santa Monica Nikkei Hall.

Fukuhara remembered the planning meetings held at members’ houses. “How I got involved with it is my father wasn’t driving a car, so I used to take him to the meetings. And I would just sit there … and they would be there having a meeting ’til 10, 11 o’clock at night. The Isseis [could do that]because they were retired. But … us [Nisei] felt that we had to go to work the next morning, so we were falling asleep many times.”

In discussions with the Nisei, the Issei were adamant about one thing, he said. “‘No JACL here. No Shimin Kyoukai here.’ That’s something that we never brought up again … They got the impression that we were trying to have a JACL chapter in Santa Monica … It was only less than 10 years [after the war]… I think there was a lot of misunderstanding, things were interpreted in a different way [but]they said JACL was responsible for us going into camp.”

Fukuhara noted that more members joined after the formation of the Fujinkai (women’s association). He added, “In some families the old folks would be thinking more about running that Nikkei Hall than taking care of their home and families, spending so much time there. But it’s a good thing that they did because it became a unified Japanese community because they had a place to gather.”

Takahashi recalled, “We had the rummage sale and we used to go around collecting [items]… We had a yearly picnic in July and then Bonen Kai (end-of-year party) probably in October or November. And then the Christmas party in December … We had the Shinnen Kai (New Year’s party) in the beginning of the year … At the end, we just had the Bonen Kai and the Shinnen Kai.”

Ohigashi said that right after the war, local Nikkei had difficulty getting re-established and made use of tanomoshi — a rotating credit association in which members made regular contributions to a common pot to be used for business startups and other major purchases. At the same time, he said, they got together for recreational activities like jewelry-making classes, a dancing club, and potlucks.

Later, the Santa Monica community pooled its resources with Venice and West L.A. to build the Ireito, “dedicated in memory of our pioneering Isseis.”

“Whenever event [was held]like New Year’s party, picnic, we invite each other so that this area’s Japanese groups were very close,” Ohigashi said, adding, “Every year Memorial Day comes … You have a combined Buddhist church and Christian church service … Christian group and Buddhist church group was getting pretty close … Real nice to make a Japanese community in that area.”

“We had this interchanging … You come to our New Year’s party, we go to your New Year’s party, and it still has been that way until recently,” Fukuhara said. “There’s only three or four of us. We couldn’t hold a New Year’s party and invite them, so we just dropped out of it. And now West L.A. does not have a Japanese community center … It’s only Venice.”

Takahashi noted that the communities worked together again after the monument was damaged by the January 1994 Northridge Earthquake. Repairs were finished in time for that year’s Memorial Day service.

The three board members “are looking to the other organizations that will carry on the memorial service not if, but when another earthquake happens,” said Steve Ohigashi, Yutaka’s son. “It can be reconstructed with the proceeds that they are given.”

Future of Building

In contrast to efforts to preserve the Tuna Canyon Detention Station site in Tujunga and Historic Wintersburg in Huntington Beach, the Nikkei Hall members are not standing in the way of demolition.

"We’d like to keep it, honto [really], but all Isseis are gone. Niseis too, almost 95 percent are gone,” said Yutaka Ohigashi. “So we can’t do it anymore after this. Children’s generation doesn’t want to stay in Santa Monica. Everything’s so expensive. So they move out some other places. There’s not many Japanese anymore … so we couldn’t help it, actually.”

Fukuhara said of preservation proponents, who did not show up at a meeting he attended, “They want the building to be retained and none of them live in Santa Monica. I don’t recognize any of the names, so I don’t know where this group is coming from. But … the city is listening to them.”

“We’re not sure how strong the opposition is, but the three [board members]signed a resolution, right before they resigned from being board members, saying, ‘We support the new buyers in the demolition of the building.’ So the new buyers have that ammunition. It’s not clear where all of this is going.”

Whatever happens, the sale itself will not be affected.

As a historical footnote, Fukuhara noted that Keiro was interested in the site many years ago. “They were very serious about it because they had so much demand from people from the Westside because they had to travel so far to where Keiro is … in Boyle Heights.”

Today, Steve Ohigashi said, part of the site’s appeal is its proximity to the Expo line.

Regarding the sale, he emphasized that there is “absolutely zero personal financial gain” for the board members.

When and where the plaque will be placed is impossible to know until there are firm plans for the site, Fukuhara said. “It could take a year easily, maybe two years, to develop that piece of property.”

LATE BULLETIN: The Santa Monica Landmarks Commission voted on May 14 to designate Nikkei Hall as a landmark. A more detailed report will follow.

* This article was originally published in The Rafu Shimpo on May 21, 2018.

© 2018 J.K. Yamamoto