Read “Part 4: Neighbors/Next Door” >>

Monsters 1950 Shōwa Year 25

化け物 昭和25年

From a leaflet from the U.S. armed forces made available to the occupation soldiers during the strongest period of attempting to implement the anti-fraternization policy which tried to discourage relations between Japanese women and occupation personnel:

“[Japanese women] have been taught to hate you. They do as their men tell them, and many of them have been told to kill you. Sex is one of the oldest and most effective weapons in history. The Geisha girl knows how to wield it charmingly. She may entice you only to poison you. She may slit your throat. Stay away from the women of Japan, all of them.” (Time Magazine, 27 August 1945)

What racisms and gender-constructions and violence did leaflets such as these reinforce, reproduce, construct? It soon becomes the normal and everyday because it is made so. For years. Does it just stop, cease to be alive when the leaflets disappear or when atomic bombs are dropped or when people marry? How long do these words form lives?

1950. American soldiers were all around all the time. I was still afraid of them. My friend Mieko and I would talk about how the Japanese soldiers looked so handsome and hot (kakko-ii) in their uniforms. My older brother was a soldier. He had fought in Burma and went through hardships there that he never spoke to me about. Now instead of Japanese soldiers, we see Americans. Everywhere. Jeeps all over, Walking around, usually in bunches. They looked sexy too. Even the women soldiers, they were sexy. We’d never seen women soldiers before! I wanted to be around them all. They beat our soldiers. They won the war. I was afraid of them. We were told by some people in the neighborhood that the Americans were monsters and they would rape us. I wasn’t scared but I had to believe it too.

One day Mieko and I decided we would try to get closer to the Americans. Yes we grabbed the candies and chocolates they threw from their jeeps when we were younger, but now I want to see them in a different way, closer. We knew about the U.S. military base that had been set up just a little walk from Mieko’s house. So we walked slowly with our arms linked with each other at the elbows so we wouldn’t be kidnapped so easily by the monsters.

On this day we decided to go, there must’ve been something special going on. As we reached a huge and endless wire-picket fence, we see hundreds, or thousands of American soldiers in straight lines, line after line, on the other side of the fence. There were huge airplanes there and tanks and jeeps everywhere. American soldiers were everywhere in crisp uniforms. We heard some other soldiers in different uniforms—probably officers, screaming something at them we don’t understand. There were hundreds of us Japanese girls there, leaning against the fence, peering through, staring and ogling and wondering, in awe. We were attracted. But there was something very familiar. We watched our brothers and friends and uncles in similar lines with similar people yelling orders. So it must’ve been the same with Americans.

As we got closer, Mieko and I wondered “donna kao shiteru no ka ne, Amerika-jin wa?” (wonder what kind of [true] faces Americans have?). We stayed clinging to each other as we leaned our faces through the spaces in the wiring, our noses sticking through, our eyes piercing and big. We looked to see American faces, the faces of the enemy my brothers and uncles went off to fight against and who killed my older sister in the Hiroshima bomb—the monsters.

I notice one soldier. He looks like he is my age, like 16 or something. He’s a boy! I see beads of sweat. I somehow see the look of fear in his eyes. I slowly work my stare down his body and notice that the hand holding his huge military rifle, is shaking, trembling. Why is he trembling? I turn to Mieko and ask her. She says “Kowai no yo, kitto. Amerika wa ima Chōsen de sensô shiteru no yo” he’s probably scared, you know, America’s now fighting a war in Korea.

Then we both realized…Americans were human too! This boy in his uniform was scared. I felt sorry for him. My body shook. Suddenly I felt different. I began to see all of the soldiers’ faces. They were all different now. They were boys like our soldiers who went to war and never returned. The tanks, the jeeps, the planes, the rockets, the uniforms, the faces, the shaking, the sweat, the guns, all rolling by, rolling by, more and even more, an endless parade.

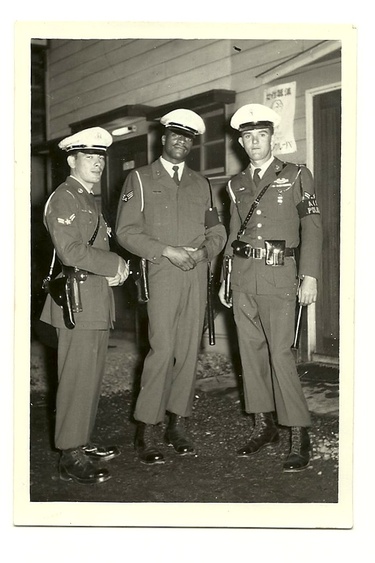

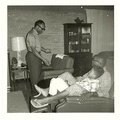

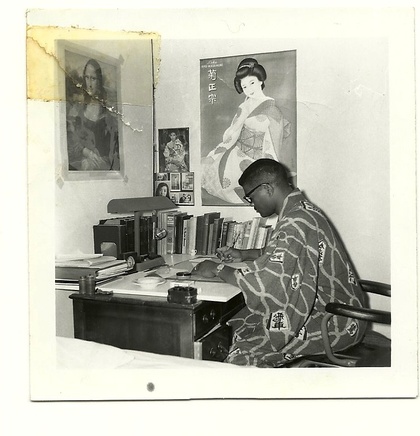

Dad at his study in the house on base in Japan, completing the factors of orientalism and the US Occupation of Japan, Black Orientalism in the domestic domain

Yuu Luv Neega Bitch!!!!!???? (You love nigger bitch!!!!!????) Then the throwing of whatever was near: cups, bowls, plates, forks and knives. Things flew at Dad, then shattered all over the wall, the floor, the table, the chair. Dad would silently open the door to leave the house while he quietly yet sternly told her “don’t yell at me woman” as objects flew at him in rapid succession from Mama.

She neega bitch Uguri neega bitch!!!! (ugly nigger bitch). She had found the photos of beautiful black “woman-friends” that Dad had hidden in the folds of the encyclopedia sets in our home. He must’ve thought that since Mama wouldn’t/couldn’t read them, the photos were safe there. But Mama cleaned every nook and cranny. That day, during one of those cleanings, she found those photos. She wondered why she was alone most of her life, in that house, raising me. Where was he every night? He was never home, even when he was supposed to be the father of the house.

Sometimes I wouldn’t see Dad for two or three days afterward. This happened two or three times when I was a kid. Our home was hardly ever calm unless it was late at night or early in the morning. But Dad never raised his voice or hit or yelled. But Mama did, though. The more Dad became quiet, holding things in, the more angry Mama became. She wanted expressions, warmth, companionship, something Dad couldn’t give her. Dad was a charming man who was peaceful and controlled. And when she would use the word nigger…it was meant to hurt him. It also hurt me when I heard it. It might’ve been the only counter-force she had to fight a battle with a man. American man. Victorious. Occupier. Class inferior. A warrior against the occupier white America.

To counter the dutiful geisha-wife-that-must-serve-him image, she began questioning that since before the war with Japanese men. Although for the Japanese men, she didn’t need to be a gentle geisha, she certainly had to know her place as second-class and subservient to men’s commands. In the postwar period, the demands of becoming the “correct” Japanese woman that the elite Japanese men propagated amongst their class, was now deployed across the entire populace with the help of the Americans, Brits, and Australians. What were the monsters that now ran rampant in our home in an open way? Where were they from? Wasn’t this now, an impossible place? What now would love act like, look like, feel?

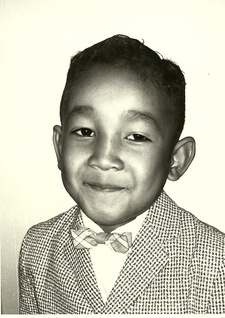

I began to understand the complexity of race and gender, in those early years, even if I could not articulate. I began to understand at this early age, that life was a not-so-simple thing. And as much as Mama was my caretaker and savior during my tiny years, those times marked a beginning of my wanting to separate from her and to recognize an aloneness that no one could assuage. There was something, I thought for awhile, that she hated in me.

And Dad couldn’t be a solace for me either. Whenever I did something he didn’t like, he would always say to me: “you’re your mother’s son.” He made me separate from him whenever I displeased him. A quiet exclusion. I began to know my place. I became a symbol as much as I was loved. Perhaps love is demarcated with my being a series of symbols like Mama, like Dad. The three of us were a nexus of displacements by nation, race, and gender. I was already defeated in a space alone, alongside, but not the same space as Mama. Or Dad. But Mama had her own battles—those of having to be my mother.

“You ain’t nothin’ but a nigger bitch!” the white woman said to Mama in the PX. There were three of them standing with their shopping carts in the aisle. Mama had brought me with her shopping at the PX.

“YOU SHUT UP!!” Mama yelled at them. The three white women came up to Mama. Mama rolled up her sleeves and her face changed into some kind of monstrous expression I became afraid of. Just then, a tall white man came and asked if anything were the matter. The three white women hurriedly left the aisle to take their carts to the check-out stand.

When Mama and I left the PX, she gripped my hand and we stopped in our tracks. I looked up to see her looking all around, checking to see if those women were around. They called her those names because they saw me. They knew that my Dad, her husband, was black. I was the cause of Mama’s pain, I thought.

This is an anthropology of memory, a journal and memoir, a work of creative non-fiction. It combines memories from recall, conversations with parents and other relations, friends, journal entries, dream journals and critical analysis.

To learn more about this memoir, read the series description.

© 2011 Fredrick Douglas Cloyd