A California Writer on the Aunt He Never Knew He Had—and the Lessons She Taught Him

Is there a family trait more common than keeping secrets?

These secrets can have hidden costs. When we leave a place or person behind, we don’t know what becomes of them. We miss out. We cut them out of our familial history.

These secrets can even make us miss the entire life of a loved one—a burrowed family secret, not passed down, and brought to light only in late harvest.

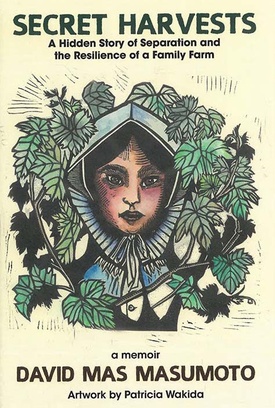

That’s one lesson of the most thought-provoking California story I’ve come across in years. It’s told with heart and heightened imagination by David Mas Masumoto, the Central Valley writer and farmer, in his recent memoir Secret Harvests.

The book ranges widely but at its center is Shizuko Sugimoto.

She was the sister of Masumoto’s mother. But he didn’t know she even existed until about a decade ago, when a Fresno funeral home called to ask if Sugimoto, who was 90 and appeared near death, was related.

He was skeptical about the call at first—could this be a scam?—but he went to meet her and began talking with family members about her. In the process, he pieced together many elements of the life of an extraordinary California woman whose very existence had been a family secret.

Sugimoto was born in Fowler, California in October 1919, daughter of a family of farmworkers of Japanese heritage. At age 5, she contracted meningitis, which attacked her brain. No one called a doctor. No one knew what to do.

The illness left Sugimoto with an intellectual disability. She would never again complete a full sentence or thought. In the recollections of Masumoto’s family, she was described as “confused, fuzzy, irritable, and difficult to comfort, traits that will linger for a lifetime.”

She was 23 in 1942, when the family was ordered to evacuate to Arizona as part of the government’s incarceration of Japanese Americans. The burdens on the family were immense—it was just before the harvest, and they were being evicted from their rented home. How could they survive in a concentration camp?

The father went to Arizona, and died within a month. But Sugimoto remained in California. A few days before the evacuation, the family turned her over to a county sheriff, making her a “ward of the state.”

It’s believed that Sugimoto lived in various institutions from 1942 until the early 1950s. It’s unclear where. Masumoto learned that some relatives had spent years searching for her after World War II, and may even have visited her at a facility in Porterville. The story goes that once they found her and visited her, they believed that she was doing better than she might have done with her own family, who were trying to rebuild their lives after incarceration. So they left her where she was, and resolved not to speak of her again.

Other family members who had known Sugimoto were left to assume she had died. But she had lived, moving between institutions for decades. Masumoto would learn that she spent several years, until the 1970s, at the DeWitt State Hospital in the foothills above Sacramento. For a time, she was at a Fresno-area facility only a few miles from his farm in unincorporated Del Rey.

Sugimoto had been living at the Golden Cross nursing home for 13 years when Masumoto received the call asking if he was the relative of a person whose existence was unknown to him.

“How do you tell your family that after seventy years, you ‘found’ their sister and aunt?” he writes. “None of us had seen her since 1942. No one knew anything about her. There are no photographs of her existence.”

When he went to see her, she had suffered a stroke and was in bed, dying.

“I am struck by her size, small and compact, folded in a fetal position. She appears comfortable, breathing gently as if asleep. She lays motionless and alone, real and authentic. This is not historical research conducted safely behind words, photographs and artifacts. I touch her warm hand, feel a bony shoulder, hear a soft sigh as she moves her head to one side. She embodies all that is wrong and right in the world, the sorrow and joy of life, the guilt and happiness of family. She delivers light to our dark past; she complicates and completes us.”

But that was not the end of the story. Masumoto got to know the staff that cared for Sugi, as they called his aunt. In the book, he praises them, and gives his due to the system that kept her alive into her 90s. The caregivers tell him of her feistiness, how she loves to tease and tickle them, how she adores music and dancing, how she wanders the halls, and how she drinks her morning coffee and then throws the cup behind her.

“She is a real character,” he writes. “Sugi has a home here. …Her disability is not a punishment and not a cure… She refuses to believe anything is wrong with her.”

As Masumoto and his family were making plans for her funeral, one day, amazingly, Sugimoto woke up. She returned to moving through the halls. She playfully kicked Masumoto in the leg. “Shizuko came to life and visits us,” he writes. “She is a living ancestor, awakened to illuminate. She no longer lives in the shadows and now steps into the light of family and our history.”

When she later died, shortly before her 94th birthday, she was the oldest client at the Central Valley Regional Center. At her funeral, the family passed out plastic cups. Mourners pretended to sip coffee, and then tossed the cups blindly behind them.

Sugimoto was interred in the family mausoleum, and Masumoto dedicated a bench at the Fresno Fairgrounds—she loved the Big Fresno Fair—to her and “those with disabilities and special needs who were separated from their families” during the World War II relocation and incarceration of Japanese Americans.

When I spoke with Masumoto recently, he talked about Sugimoto’s story, and the roles racism and discrimination against people with disabilities played in it. But we also talked about secrets, especially in families, and all that we miss when we keep them.

“I now force myself not to look away,” he said, adding: “Memories can and should change.”

*This article was originally published on the Zocalo Public Square, “Connecting California” column on August 1, 2023.

© 2023 Joe Mathews