Upon finishing their undergraduate studies in the Soviet Union, Michiko and Américo had to decide their immediate future. Their daughter Emiko had already been born and they needed to find a stable job. Michiko did not dislike going to Mexico because she had met a large group of Mexican students with whom she lived and established a good friendship. Faced with this dilemma, they considered that the most convenient thing would be to settle in Mexico because Américo would find a job more easily than in Japan and she could further her studies in History at a Mexican university.

Upon arriving in Mexico, Américo began working at the Mexican State oil company, PEMEX, as well as beginning to teach at the School of Economics of the National Polytechnic Institute. In 1967 Michiko was accepted as a master's student at the College of Mexico. In this institution, the Center for Oriental Studies had been established, in charge of researching and training students in that cultural area and, in particular, in the history and culture of Japan.

The year 1968 marked a watershed for youth in many countries around the world. The American aggression against the people of Vietnam and the massive and growing involvement of that government and its powerful army generated great indignation worldwide. In May of that year, students from universities in France began a strike that lit the fuse that would ignite student protests in North American, Japanese and Mexican universities. The students were not only opposed to the war against that small Asian country but also against the authoritarianism and established hierarchical order. The slogan “forbidden to prohibit” that was spread in the French May became a youth slogan in other countries. The student movements worldwide represented a true cultural revolution that would leave deep marks in the decades to come. Michiko and Américo were not immune to these events.

In July of that year, in central Mexico City, a skirmish between students from two schools sparked a violent police crackdown. High schools and various universities began to protest against the way in which the students had been acted upon. The students' demand was to request the dismissal of the police commanders, but the government's response translated into more repression. The door of High School number one was knocked down with a grenade to chase the students who took refuge in their school. The students of El Colegio de México went on strike, as did many public and private universities in the city, due to the intensification of the government's repressive measures.

The protests continued throughout the following months. On October 2, a week before the opening of the Olympic Games in Mexico, thousands of students gathered once again to demand an end to repression and a public dialogue with the President of the Republic himself, Gustavo Díaz Ordaz. The protest in Tlatelolco ended with the entry of the army and paramilitaries who shot at the unarmed crowd. Américo, as a professor at the Polytechnic, was among the students and, although fortunately he was not injured, he was detained by the police along with hundreds of other students. Michiko, upon learning of the massacre, dedicated herself to searching for him throughout that night in hospitals and detention centers. It was not until the next day that she found out that her husband was imprisoned along with more than 700 students. The following months would come with bad news as Américo and hundreds of teachers and students received sentences of between 10 and 15 years in prison for fabricated crimes.

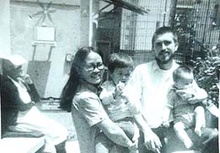

Michiko at least had her student scholarship and through the support of friends and family it allowed her to overcome financial difficulties and her new pregnancy. In these dark times, at the beginning of 1969, a light came when the couple's second son, Sergei, was born. The birth of the baby filled them with joy but increased Michiko's workload, who did not stop pursuing her master's degree. That year represented for Michiko a period of great difficulties but also of an intense relationship with the country to which she had arrived.

Mexico supported the immigrant and through the support she received from the authorities and her classmates at El Colegio, they allowed her, in such complex circumstances, to finish her studies in 1970. The work she presented for her degree was called “Peasant Movement in the Formation of the Modern Japan”, research that would be published later. 1 Tanaka's research represented a great contribution to understanding the participation of the Japanese peasantry as a social subject in the collapse of the Tokugawa regime in 1868 and in the construction of modern Japan.

In 1971 the Tanaka family received another great news. The teachers and students who participated in the student movement were released through an amnesty. Two years later, her third child, Laura, was born, and Michiko became a full professor at El Colegio de México, in the Center for Asian and African Studies, the name by which the previous Center where she had studied would be called. As part of this new impulse to research and training of students in this area of El Colegio de México, Michiko went to Princeton University in the United States in 1975 to carry out his doctoral studies where he would graduate with the research “Popular Culture and State in Japan 1600-1868. Youth organization in the village government. The work deepened the knowledge of the daily life of peasant communities in Japan and their role in the organization and community mentality of modern Japanese society. 2

Michiko Tanaka not only took on the task of carrying out her own research but has been the driving force for various specialists to contribute to the analysis and dissemination of the history of Japan. Some of these fruits resulted in the publication of the “Minimal History of Japan” and the “Documentary History of Modern Education in Japan”, among many other texts.

Another fundamental aspect of Tanaka's work is her leadership as coordinator and promoter of teams of researchers who have collected, compiled and translated into Spanish thousands of documents from the history of Japan from 1868 to 2012. The collection “Politics and Political Thought in Japan” , which brings together all these documents in several chronological volumes, has become a fundamental tool for students and specialists who have been training in the last four decades throughout Latin America dedicated to the knowledge and history of Japan.

It is pertinent to mention, from another perspective, the participation and decisive impulse that Tanaka has given to the constitution and operation of the Latin American Association of Asian and African Studies (ALADAA) and other research centers in different Latin American countries. The conferences and exchanges in this Association have repeatedly allowed exchange and discussion about Japan from the perspective and eyes of researchers from the region.

Michiko Tanaka is a Japanese woman with strong roots in Mexico not only for everything mentioned above but also for the organization and promotion of the peasant communities in Tlayacapan, Morelos. Professor Tanaka is recognized not only as an advisor in her vast professional field on Japan but also for participating in the organization of farmers who produce and market various organic products such as vegetables, fruits, tortillas and tlacoyos that the Cooperativa Frutos de Tlayacapan distributes for our delight. .

In this year of 2023, we celebrate with pleasure and joy the first 80 years of life of a girl who was born in the middle of the war in her native Japan but who laid down deep and fruitful roots in Mexico. We also celebrate 50 years as a professor at COLMEX, work that has made her the most important expert and trainer of specialists in the history of Japan in Mexico and Latin America.

Grades:

1. The book is out of print but can be consulted in the following electronic link .

2. The electronic edition is located here .

© 2023 Sergio Hernandés Galindo