My high school yearbook is a well-worn treasure. After leafing through it all these years, the binding along its spine has fallen off. The faces and names evoke smiles, chuckles and tears. Some gained fame and fortune, built successful businesses or have talented offspring. But what if your yearbook contained no photos and only the last name and first initial of your schoolmates?

That is the unimaginable reality for graduates of the World War II-era Military Intelligence Service Language Schools. The classified nature of the Military Intelligence Service and its language schools were the justification for concealing the full names of the personnel while honoring their attendance and completion of language training.

For Americans of Japanese ancestry and others, the language specialty — especially Japanese military vocabulary — required more than six months of schooling that included reading, writing, speaking and the ability to translate Japanese to English and vice versa. The graduates were then sworn to secrecy about their deployments. Even after being discharged, they maintained their oath to secrecy until the mid-1970s when their exploits were finally made public.

However, as author Lyn Crost wrote in her book, Honor By Fire, “the secrecy they had to maintain denied them public acknowledgement of their deeds.”

Thus, for too long, MIS veterans could not answer the question: “Daddy (or Grandpa), what did you do in the war?” Nor could their families turn to a source with the information, unlike the 100th Infantry Battalion and the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, which had a centralized headquarters where records of awards and decorations were maintained and later published in books or displayed in museums and education centers.

Prior to America’s entry in World War II, several Nisei were already serving as interrogators, interpreters and translators on secret military intelligence missions in the Pacific region. Their language proficiency and intelligence-gathering skills were impressive and led to the recruitment of prospective Japanese linguists. A large number of Hawai‘i volunteers enlisted in July 1943.

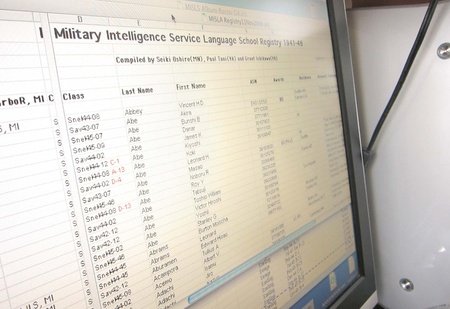

Decades after the war, three former MIS linguists—northern Virginia residents Grant Ichikawa and Paul Tani, and Seiki Oshiro of Burnsville, Minnesota—formed the MISLS Registry team to identify the full name and Army Serial Number (ASN) of the Nisei linguists who graduated from the MIS Language Schools. But they didn’t stop with just names. They researched individual post-language school deployed assignments, military occupational specialty (MOS), and awards and decorations. The result is the MISLS Registry. (Note: The acronym MISLA was adopted when the original spreadsheet was converted with new software.)

In the days before digitization made computerized records available, the three made in-person visits to the National Archives and Records Administration in College Park, Maryland. In the War Department’s roster in the Washington, D.C., archive, they found 23,000 Nisei soldiers’ full names and ASNs.

Seiki Oshiro and his late wife, Vici (née Victoria Ann Parker), would drive 19 hours from their Minnesota home to the NARA branch in St. Louis, Missouri, taking turns at the wheel and stopping only for gas and restroom breaks. Their homemade peanut butter and jelly sandwiches sustained them during the long drive and were their snacks during their weeklong stay in St. Louis.

During their three trips, they retrieved information on 3,690 Nisei who had served during the occupation of Japan. Their work, and that of others, such as Aiko Yoshinaga-Herzig, Rodney Kamiya, Jimmy Yamashita, and Jim McIlwain, contributed to the records of 7,362 personnel of all ethnicities in “The Entire Army Global Areas MISLA Registry.”

These linguists were assigned to the Pacific Military Intelligence Research Center, or PACMIRS, in Washington, D.C., and in Hawai‘i. They also served in battlefronts in China-Burma-India, Central Pacific area (Saipan, Iwo Jima, the Gilbert Islands), Okinawa, Australia, New Guinea and the Philippines, and gathered intelligence in Alaska, Korea and in occupied Japan.

In Honor by Fire, Lyn Crost highlights a stumbling block encountered by the researchers. “Language teams were with every unit on the island[s], but, because they were designated TDY (temporary duty) for the invasion[s], as they were in all other invasions, most of their records are lost to history.”

In a letter to Oshiro, the archivist of Modern Military Records at NARA in College Park highlighted a second stumbling block, writing, “. . . unfortunately, rosters for units serving in World War II from 1944 to 1946 were destroyed in accordance with Army disposition authorities.”

Oshiro, who is 95, was born in Päpa‘aloa on Hawai‘i Island and is the only surviving member of the MISLS Registry Team. With information gathered by his fellow researchers, MIS veterans and official documents, he compiled an excel file of 7,362 records and separate spreadsheets for 124 “small size” units of linguists, providing as much information as possible in summaries edited from official documents. He has contributed years of volunteer time, computer knowledge and materials to this decades-long project.

Descendants will be especially interested in the military occupational specialty, which includes a wide range of job titles: “Interpreter,” “Translator,” “Interrogator,” “Investigator,” “Counter-Intelligence Officer,” “Civilian Censor,” and “Voice Interceptor.” MISLS graduates who attended Cooks and Bakers School translated orders from American officers and taught the Japanese kitchen workers how to prepare American food for the occupation forces.

MIS linguists who were truck and Jeep drivers were especially valuable to American officers because they could read Japanese maps and road signs. Linguists who were able to speak three languages—English, Japanese and Okinawan—saved countless lives by persuading Okinawan civilians to come out of the caves they were hiding in during the Battle of Okinawa. Nisei linguists also played key roles in the war crimes trials after Japan’s surrender.

While the Oshiro, Ichikawa, and Tani Registry research team will probably always feel that their project is incomplete due to the stumbling blocks they faced, what they have compiled and documented is, without question, helpful. A local woman who wished to remain anonymous recently asked whether information existed about her father, who rarely talked about his wartime experiences.

After hearing the stories of the World War II service of her friends’ fathers, she wanted to learn more about her own dad. His name was located in The Registry. A copy of his discharge document confirmed his birthdate. The Registry’s data also listed his rank, serial number and all of the locations where he had served and in what occupations. Her question, which seemed to have no answer at first, surprisingly generated detailed information about her father’s history. Hopefully, she will share what she learned with other family members.

Researcher Jim McIlwain of Massachusetts, whose spreadsheet, “Soldiers and the Camps,” includes the 33,000-plus soldiers of the 100th Infantry Battalion, 442nd Regimental Combat Team, Hawai‘i’s 1399th Engineer Construction Battalion, and Military Intelligence Service, commended Oshiro’s work, calling it “an exhaustive compilation.”

“He is a meticulous, indefatigable researcher and compiles the information he collects in useful, detailed documents,” commented McIlwain. He said the fact that the MIS linguists were assigned to a variety of locations around the world and particularly in the Pacific theater, where they often served in very small groups, or even alone, were a challenge Oshiro overcame.

“Seiki knows his way around the publicly available government databases as well as those that are not easy to access,” said McIlwain. Collaborating with Oshiro has been “a pleasure,” McIlwain added.

Metta Tanikawa, who has worked for several Nikkei and AJA veterans organizations, applauded Oshiro’s work. Tanikawa is part of the Japanese American Veterans Association’s research team in Washington, D.C. She credited Oshiro with providing information for the MIS awards tally, which attempts to document all the awards earned by the MIS Nisei in World War II. The San Francisco-based National Japanese American Historical Society is the keeper of that important document.

Tanikawa called Oshiro an “excellent” source of information on the World War II Nisei MIS veterans. He can tell you when they enlisted, what language school class they completed at Camp Savage and Camp Snelling, where they served and sometimes what awards they received, she said. “He is responsive and very generous with his expertise,” said Tanikawa. “Seiki is amazing to work with.”

*This article was originally published in The Hawai‘i Herald on July 21, 2023.

© 2023 Drusilla Tanaka