Bring on the immigration fever

In the previous article (No. 32) , "From Americamura in Shima City, Mie Prefecture," I introduced the fact that Takeuchi Kosuke, the grandfather of Takeuchi Toshikazu, the owner of a jazz cafe that I stopped at during my trip, traveled to the United States and compiled the history of the Japanese community that was formed in San Pedro near Los Angeles in a book called "The Development Record of the San Pedro Compatriots."

Kosuke was from the former Katada village in Mie prefecture, and I mentioned that Katada village produced many immigrants to America and was called "Amerikamura" at the time. But why did people from this area start going abroad? After researching on the Internet, I found that one woman had a big influence on this.

The woman's name was Ito Riki. She was from Katada Village and was a pioneer who was the first person from this area to emigrate to America. It is said that many people from Katada Village relied on her to get to America.

Satoki was also introduced in the Ise-Shima tourist guide, and I learned that the pine tree she brought back with her when she returned to Japan has grown well and remains in her hometown as the "Oriki Pine." She was also introduced as the first Japanese person to become a licensed midwife in the United States.

Satoki went to America in 1889 (Meiji 22). The first Japanese person to come to San Pedro, where Mr. Takeuchi, also from Katada village, had put down roots, was around 1899, and Mr. Takeuchi went to America in 1918, so Satoki was quite early in coming to America for someone from Katada village.

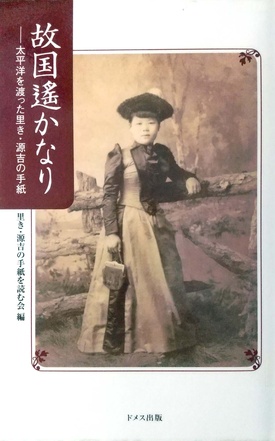

What kind of person was Ito Riki, the woman who brought immigration enthusiasm to her hometown, and what did she do? Upon researching, I found the answer in a book called "Far from Home: Letters from Satoki Genkichi Who Crossed the Pacific Ocean" (Domesu Publishing).

Published in 2011, this book presents letters written by Ito Riki and her de facto husband Utsunomiya Genkichi (also known as Yamada Genkichi) to Satoki's daughter Moyo and her family, whom they left behind in Japan, and uses the letters to trace the life of Satoki and her family.

The editors are four members of the "Satoki and Genkichi Letter Reading Group." One of them, Masao Hagiwara, who was involved in the compilation of the former Ise City History, has been interested in Satoki for many years, and while researching to uncover his footsteps, he came across Yasuhiko Adachi, Satoki's great-grandson. He discovered that Adachi had kept letters between Satoki and Genkichi, and he became one of the four to produce this book.

Hagiwara once lectured on female divers at Mie University and asked prolific essayist Yuji Kawaguchi to help with the publication. Kawaguchi then invited Toshio Yoshimura, a specialist at the Mie Prefectural History Compilation Office, to help him read the old letters. The four of them published the book as the "Reading Group."

Leaving a daughter behind in Japan

Let's trace the life of Ito Riki through this book.

Ito Riki was born in Katada Village, Ago County, Mie Prefecture in 1865 (the first year of the Keio era) as the third daughter of Ito Unrin, a doctor. After studying at Katada Elementary School, she moved to Tokyo around 1880 (the 13th year of the Meiji era) to look after her eldest son, Ichiro, who had moved there to study medicine.

In 1887, she married Nakayasu no Kami, who was also from the Shima Peninsula and whom she met in Tokyo, but it is believed they separated soon after. Around this time, Satoki worked as a live-in maid at an American's house in Yokohama, and later worked at the home of another American. When this family returned to Japan, Satoki decided to go to America.

In 1889, he set sail from Yokohama to San Francisco on the American passenger ship "City of Rio de Janeiro" (note) . Two years later, Satoki's daughter, Moyo, was born. The father is believed to be American. Around 1892, Satoki began living with Utsunomiya Genkichi. In 1894, Satoki returned to Japan with Moyo. In his hometown of Katada, people were amazed to see Satoki in Western clothing, and because Moyo had blue eyes, they assumed that she was the child of an American.

People were interested in Satoki's words about the high wages and other rich things in American life. When Satoki left for America again in 1895, he invited young people from his hometown of Shima, including Katadamura, to go to America with him, and seven young men and women who agreed to his idea went to America with him.

During his return to Japan, he left his daughter Moyo with the family of Susumu Kato in Kurihama, Kanagawa Prefecture, and when he returned to the United States, he took her back with him. However, he left Moyo with Kato's family again when he returned to Japan. Satoki, who was planning to start a business in the United States, was planning to go and pick up Moyo if he was successful.

In 1898, Satoki returned to Japan and visited Moyo, who was in the first grade of elementary school. However, he did not bring her back with him, and the mother and son never met again until Satoki's death in America.

Satoki, who had a tomboyish drive and entrepreneurial spirit, took on various businesses and jobs, such as leading young people from her hometown to America. After arriving in San Francisco with the young people, she put on a "female diver underwater show" in a corner of Chinatown in the city, attracting spectators. In her hometown of Katada, it was common for women to dive as female divers, so Satoki and the women who accompanied her likely did this with no difficulty.

However, the practice of having women dive with ropes around their waists was criticized in the United States as being an act of cruelty to women, and so the practice had to be discontinued.

He also imported and sold Japanese paintings from Japan, and ran a restaurant and a billiard parlor, but these were not always successful, and he and Genkichi supported themselves by working for American families.

Although he maintained communication with his daughter and her family through letters, he never returned to Japan after seeing his daughter as a child. We don't know exactly what Moyo thought, but she was bullied as a child because of her American appearance, and at the start of the war she was even accused of being a spy for her correspondence with the United States.

I want to go home, but I can't

After the war, in 1950, Satoki passed away at the age of 85 in Santa Maria, central California.

It is not clear why he did not return, but he had a strong desire to return someday. In a letter written to his daughter's husband in 1931, he wrote, "I want to return, I want to return, I want to return to my birthplace. But I cannot bring myself to go back so easily. Although I would love to see her, I do not want to return before the dawn of my dreams arrives (some parts have been edited for easier reading).

For Satoki, who had an entrepreneurial ambition and dreamed of success, I surmise that he felt that he could not return home even if he wanted to unless he could bring home a patina of success.

To digress, I feel that the feelings of Morikami Sukeji, who was one of the Japanese immigrants in the Yamato Colony that existed in Florida and who stayed in the area until the end and made a name for himself, are similar to those of Morikami Sukeji, who repeatedly said he wanted to go home, and never did. He also became the owner of a vast amount of land, but it seemed that he felt that he had not been successful in any business ventures, and that as time passed, he began to feel a gap between him and his homeland, which made it difficult for him to go back.

Satoki was not successful as a businessman. However, those who traveled to America relying on Satoki found work there and sent money back to their hometown of Katada. This may have inspired many people from Katada to travel to America from the end of the Meiji period to the beginning of the Taisho period, and the immigration craze continued into the Showa period.

According to a survey conducted in 1942 (Showa 17), the year after the outbreak of war between Japan and the United States, there were 232 people from Katada village (including second-generation immigrants) living in the United States, and the population of Katada village at the time was approximately 4,000.

"The total amount of money sent by the settlers to the village post office amounted to three times the village's budget," he said.

Yuji Kawaguchi, one of the editors of "Homeland Far Away," had this to say about Satoki, who set the precedent for immigration to America and had a major impact on his hometown:

"She deserves to be recognized more highly for the fact that she went to America alone, despite being a woman and barely able to speak English, and had an impact on the people of her hometown. Japanese people don't often respect people who dug wells, but she should be respected."

(Some titles omitted)

Note: The "City of Rio de Janeiro" sank shortly after running aground near the current Golden Gate Bridge on February 22, 1901. Of the 210 passengers and crew, including Japanese immigrants, 128 died. It is also called the "Titanic of the Golden Gate." (See: " 3D images of the sinking site of Japanese immigrant ship released ," CNN World, December 12, 2014)

© 2023 Ryusuke Kawai