Writer’s note: Back in 2014 when I worked at University of Hawai‘i (UH) at Mānoa, I interviewed Dr. Ryuzo Yanagimachi for The Prism newsletter. For the interview, I remember doing a lot of research! He not only impressed me with his work ethic and words of wisdom, but I also found Dr. Yana to be very kindhearted and humble. Pleased with the article, he asked if I could post it on his Wikipedia page. After hearing the sad news of his passing on September 27, I felt that republishing this article, which Dr. Yana was fond of, would be a nice remembrance of his life and legacy.

* * * * *

Back in 2000, the TV show Dark Angel featured Max, portrayed by Jessica Alba, a transgenic (genetically engineered) human being who was trained to be a super soldier. Max’s DNA, being genetically augmented with feline DNA, gave her special abilities – enhanced eyesight and hearing, strength, speed, agility and stamina – making her a “superwoman.” Sounds improbable? Perhaps … but perhaps not all of it.

In the scientific world, the creation of transgenic animals has been achieved for quite some time. In 1999, glowing green mice were produced and more recently, in 2013, articles on glowing green rabbits, pigs and sheep appeared all over the news. The scientist whose research played a big part in these accomplishments is Dr. Ryuzo Yanagimachi. With a career at UH Mānoa that spanned 40 years, he is renowned globally for his research in reproductive biology, especially his pioneering work with in vitro fertilization in humans, freeze-dried sperm technology and the creation of the world’s first cloned mouse.

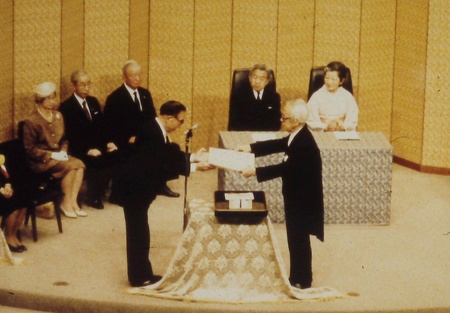

Dr. Yanagimachi is the recipient of numerous awards and honors, most notably the 1996 International Prize for Biology, which is awarded in the presence of the emperor of Japan. He was inducted into the prestigious National Academy of Sciences in 2001 and also the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development's Hall of Honor in 2003, which recognizes scientists for exceptional contributions to the advancement of knowledge and improvement of maternal and child health.

He is also on UH Mānoa’s “100 Contributions,” a list of remarkable achievements that have benefitted society, although he was surprisingly unaware of this honor until I asked him about it.

Retired in 2005 from UH Mānoa, Dr. Yanagimachi (fondly nicknamed “Yana”) is a professor emeritus, who at age 86 is busy continuing his research on the study of fertilization in mammals as well as fish and insects. I recently had the honor to interview this distinguished, yet unpretentious scientist.

* * * * *

LK: Why did you decide on UH Mānoa for your career?

RY: In 1965, Professor Robert W. Noyes (formerly with Vanderbilt University) joined the newly established UH Medical School as an associate dean and had asked me if I was interested in joining the Department of Anatomy and Reproductive Biology as an assistant professor. At that time, I was at Hokkaidō University (Sapporo, Japan) after a four-year stay at the Worcester Foundation for Experimental Biology in Shrewsbury, Massachusetts, as a postdoctoral research fellow. At Hokkaidō University, I was a temporary lecturer and was not very happy about it. Although I could have returned to the Worcester Foundation, I chose UH for two reasons: first, the other faculty members that Professor Noyes had recruited and second, the good weather in Hawai‘i!

LK: What was your childhood like? Did you always want to be a scientist?

RY: I grew up during Japan’s involvement in wars, starting from the conflict with China. World War II ended when I was 17 years old. My grandfather, the son of a low-ranking samurai, started a trading business in Ebetsu, Hokkaidō. Almost all of our relatives were merchants and talked about money all of the time. As a child, I felt differently and thought that money was not everything.

During my grammar school years in Sapporo, my older brother and his friend took me to the nearby mountains in early spring to collect frog eggs and Adonis flowers; in the summer we went to the same mountains to catch butterflies and many other insects. This was the first time I was exposed to nature. So yes, I was always interested in science, but I might have become an astronomer if I were stronger in mathematics.

LK: What has been your motivation?

RY: I was sort of a slow starter. I was 38 years old when I got a faculty position at UH. Many of my other university classmates had appropriate positions much earlier than I did. I always thought that I needed to work hard and catch up to the others when I attained an appropriate research/teaching position.

People may have thought that I was a workaholic, but because I was doing what I really enjoyed, I did not get tired even if I slept for only a few hours a night. (Chuckling.) Another motivation was that I felt it is a scientist’s privilege to uncover the secrets of nature. Unlike people, nature never lies.

LK: What was your biggest challenge?

RY: When I was in my early 20s, I was a student of civil engineering. Although I completed school, I wondered if I really wanted to devote my life to engineering. I could not forget the beauty of nature, so I decided to do what I truly felt passionate about. I had never taken any formal biology courses, so I self-studied basic biology and reentered the College of Basic Science at Hokkaidō University. My other big challenge was studying abroad in the U.S. in the 1960s. At that time, there were not many Japanese people who were studying abroad.

LK: You were the founding director (2000-2005) of the Institute for Biogenesis Research (IBR), which focuses on the study of reproductive biology and has a state-of-the-art Transgenic Core Facility. What are your thoughts on therapeutic cloning, which involves creating stem cells that are genetically matched to a patient to treat that patient’s disease?

RY: The idea is great, but I think it will still take many years to accomplish, although I hope that it will be quicker than I think!

LK: Can the research be used to help save endangered species (such as the Hawaiian monk seal, orangutan and giant panda)? Or what about bringing back extinct species (de-extinction)? There has been a lot of buzz in the scientific community about the frozen woolly mammoth that was found last year with its blood flowing intact. Could one successfully be brought to life?

RY: I think that the best way to save endangered species is to protect their environments so that they can live and breed in the proper surroundings and be able to replenish their population without being hunted. As for the woolly mammoth, it is highly unlikely that the DNA is intact due to the fluctuation of the temperature of the ice. We should instead be paying more attention to the many different species that are disappearing quickly from the surface of the Earth.

LK: What advice would you give to our students?

RY: It is important to find work that you enjoy no matter what other people say, not work that you can tolerate.

LK: Among your many achievements, of which are you the proudest?

RY: I’m proud to be one of the pioneers who contributed to the basic knowledge of mammalian fertilization as well as the development of assisted fertilization technologies. My major work was the study of the process and mechanism of fertilization in mammals including humans, not cloning and transgenesis. Cloning and transgenesis are merely two by-products of studying fertilization. Before I entered the field (1960s), very little was known about fertilization in mammals because of the difficulty in handling eggs and spermatozoa in vitro (outside of the body), so I began to study fertilization using the in vitro fertilization technique I developed.

* * * * *

The research continues at IBR and Dr. Yana’s legacy will live on for future generations to benefit from his accomplishments. When I asked him if it turned out to be a good thing that he wasn’t strong enough in math to be an astronomer, Dr. Yana laughed and said simply, “Yes, it was definitely a good thing.” But Dr. Yana also mentioned that he almost didn’t work for UH Mānoa; it was the toss of a coin by the faculty recruitment committee that determined his loss of an open position at Hokkaidō University and thus, his decision to accept the offer at UH Mānoa. He paused for a second – probably envisioning that memory – and then said happily, “It turned out to be a very lucky coin toss,” with a contented smile on his face.

|

Speed Round with Dr. Yana Favorite books? A person you admire? Favorite food? Places you like to visit? |

*This article was originally published in The Prism in Fall 2014, received permission to republish the article by the Office of Global Engagement from the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa.

© 2014 Lois Kajiwara