Wayne Mortimer Collins is an important name for my family. I first learned about this heroic, brash and outspoken attorney nearly twenty years ago while editing my uncle Hiroshi Kashiwagi’s first book, Swimming in the American (2005). I was surprised to see the book dedicated to Collins, and learned a bit about him while reading about my uncle’s struggle to regain his American citizenship after renouncing it under intense pressure by the United States government.

My admiration for Collins only deepened after hearing his son (Wayne Merrill Collins) speak at the 2014 Tule Lake Pilgrimage—learning that he pursued this legal battle pro bono on behalf of my uncle and some five thousand renunciants over two decades, all while supporting his large family as a single parent.

I learned more about Mr. Collins and the renunciant story while co-writing We Hereby Refuse; he helped to argue the cases of Mitsuye Endo and Fred Korematsu before the Supreme Court. Although Collins has been an important part of many aspects of the camp story, it’s somewhat surprising that few know who he is. Perhaps because the Tule Lake story is still so complicated and misunderstood, as well as the story of his client Iva Toguri or “Tokyo Rose,” the story of Wayne Collins himself has also been somewhat obscured.

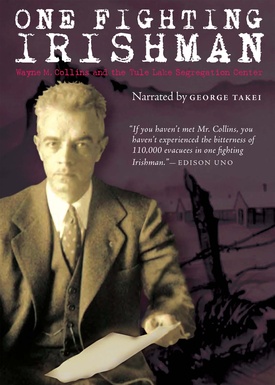

That obscurity will hopefully change with the advent of a new documentary, One Fighting Irishman: Wayne M. Collins and the Tule Lake Segregation Center. One of the community’s most notable filmmakers, Sharon Yamato, has made a documentary about Wayne Collins and his fight for justice for Japanese Americans. Known for her documentaries about the Heart Mountain barracks (Moving Walls), Michi Weglyn (Out Of Infamy), and Stanley Hayami (A Flicker in Eternity), Yamato has now turned her attention to Collins.

I was able to see a nearly-finished preview version of the 30-minute film before its premiere at the Japanese American National Museum on October 28, and hope that many others will be able to see it eventually as well. Featuring community activists including Hiroshi Kashiwagi and Hiroshi Shimizu, and historians like Brian Niiya and Eric Muller, the film covers Wayne Collins and this little-known aspect of the Tule Lake story.

Though there’s a great deal of rare archival footage, perhaps one of the most memorable parts of the film is its use of audio recordings of Wayne Collins himself, allowing viewers to experience the power of his fiery, no-holds-barred rhetoric firsthand.

I spoke with Yamato over e-mail to gain greater insight into the arduous process of making the film. Yamato hopes to take the film to other regions, including Sacramento and the San Francisco Bay Area, and is applying for film festivals as well.

* * * * *

Tamiko Nimura (TN): Can you talk about the first time you heard of Wayne Collins and in what context?

Sharon Yamato (SY): I first heard about Wayne Collins while working on a documentary on another of my heroes, Michi Nishiura Weglyn, who dedicated her landmark book, Years of Infamy: The Untold Story of America’s Concentration Camps, to him. With the high respect I held for Michi and her tenacious devotion to writing and speaking out about justice for Japanese Americans, I knew that someone she considered to be the man “Who Did More to Correct a Democracy’s Mistake Than Any Other One Person,” had to be a person of superlatives. Her words proved to be true.

TN: How, when, and why did you decide you would make a documentary about him?

SY: When I heard Wayne Collins’s son, Wayne Merrill Collins, speak at the 2014 Tule Lake Pilgrimage, I was completely blown away. Even though I already knew the elder Collins to be a man of principle, I was struck by his son’s description of the doggedness it took to engage in his lifelong fight for the rights of Tule Lake segregants in the face of a government dead set on getting rid of them.

I was particularly shocked to hear that among the reasons his fight was prolonged involved his battles against the national JACL and the national ACLU—mainly in the persons of JACL executive director Mike Masaoka and attorney A.L. Wirin. One might assume these two respected civil rights organizations and leaders were on the side of those held in camp, but they literally turned against those who they considered “disloyal” or “troublemakers.” After the standing ovation Collins received from the many Tule Lake families in the audience, I was driven to find out more.

I was also deeply moved that day by the words of another of my Nisei heroes, Hiroshi Kashiwagi, a former renunciant-turned-activist/poet/actor/writer, who spoke eloquently about the man who he later dedicated his book to, saying Collins “rescued me as an American and restored my faith in America.” The choking in his throat as he delivered his moving tribute to Collins made me realize the incredible impact this Caucasian attorney had on so many who would not be American were it not for him.

TN: On social media you mentioned that the film is the result of “Years of blood, sweat and tears.” Can you talk a bit about some of the biggest obstacles in making this film?

SY: When you say obstacles, where do I begin? First of all, delving into the ambiguous and conflicting reports of the situation at the turmoil-ridden Tule Lake camp took well over a year just to touch the surface, and I still don’t think I’ve grasped all its complexity. Aside from primary material that could only be found at the then pandemic-closed institutions like the National Archives and Berkeley’s Bancroft Library, I found there was very little secondary material available except for a few noteworthy books focused on Tule Lake.

In addition to Michi’s Years of Infamy, Donald Collins’ 1974 book, Native American Aliens, and Richard Drinnon’s Keeper of the Concentration Camps proved invaluable, and the complete cooperation of historian Donald Collins himself (no relation to Wayne Collins, now 88 years old and living in North Carolina) was instrumental in getting this story told.

TN: What kept you going during the creative process?

SY: Although writing and cutting the script down to 30 minutes was a solitary process that allowed for long bouts of procrastination, I was fortunate to have the assistance of many creative people who pushed the process along. A wonderful editor and cinematographer, Evan Kodani, whose commitment to telling stories about our history, was a perfect fit, and by enhancing visuals, he made the script come alive.

I was also thrilled to find a creative husband-and-wife team, Mike and Julia McCoy, who did all the motion graphics as well as completed the editing. When I was first introduced to them, I was deeply touched by their enthusiasm for a subject they knew little about but clearly understood its importance. It was wonderful seeing the results of their polished work, which when combined with the brilliant music of composer Dave Iwataki, made everything come together.

When I needed a shoulder to cry on, I also had the stiff one of my creative consultant and longtime friend, Nancy Kapitanoff, who reminded me that films are difficult to make and even harder to make well. So many friends were also there as trusted allies and knowledgeable scholars who kept the film honest and true—people like scholar Art Hansen, Densho’s Brian Niiya, and Tule Lake survivor Hiroshi Shimizu.

I knew the film’s subject was important when my trusty sound editor, Jon K.Y. Oh, who has finessed the sound on every Japanese American film made in Los Angeles since the beginning of time, told me he liked it and did everything he could to make it better.

TN: What surprised you the most in your research about him?

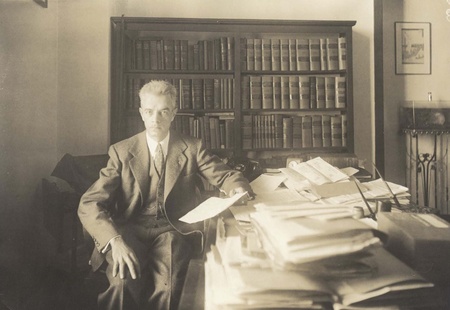

SY: Since there has been very little written about him, surprises were many. Perhaps most amazing was the amount of work it took to defend this special group of maligned Japanese Americans. After looking through his voluminous files, it was unimaginable that one man was responsible for the piles and piles of paperwork that crossed his desk. Besides the 10,000 affidavits he researched and filed, there were questionnaires, drafts, and letters that accompanied each one. There were also hundreds of lengthy legal briefs that had to be written and filed.

To cite one example, the original Abo v. Clark pleading (which was one of his four original renunciation lawsuits) involved 986 plaintiffs, more than 50 pages long, and just the beginning of a deluge of subsequent pleadings on behalf of more than 4,000 others. When you consider the 23 years it took him, you can only imagine the correspondence involved in locating all the renunciants, both in the US and Japan, and having to keep track of each individual case. Thankfully, he was helped by members of the Tule Lake Defense Committee, headed by Tex Nakamura, a man who deserves a film of his own.

I was also amazed to learn that Collins, who was orphaned as a child with little formal education, was gifted with a thirst for justice and keen intellectual prowess. A brilliant man and prolific writer, he immersed himself in books, particularly Greek and Roman classics. His passion for justice was described by his son at the Tule Lake Pilgrimage in his recitation of a passage in Plato’s Apologia of Socrates that his father gave him. In it, Socrates describes how he could never work for the state or any governing body lest his pursuit of justice be compromised.

TN: Anything you wish you had been able to include in the final cut that didn’t make it in?

SY: Aside from the passage from Plato that I didn’t include, there was much more to be said about the work Collins did at the Department of Justice camps and Crystal City. I also would loved to have included more about the strong personal bonds he formed with people like artist/designer Bruce Porter and Asian art dealer Senri Nao, whose daughter, Chiyo Wada, became Collins’s principal office assistant.

I also had to omit a very sweet story about a young newspaper boy, Tommy Nakagawa, who Collins befriended outside his office and then helped provide medical treatment for a condition that caused his stunted growth. Nakagawa ended up becoming a prize-winning jockey.

TN: In the last thirty years or so, more stories about Japanese American resistance to the incarceration have emerged. Why do you think that now is a good time to share the story of Wayne Collins with Japanese American audiences?

SY: There was (and sadly, still is) a time when it was shameful to admit you were from Tule Lake. I vividly remember attending my first Tule Lake Pilgrimage in 1996 when it was clear that former Tuleans were barely beginning to emerge from the shadows. Twenty-one years later in 2017, the JACL agreed to issue a somewhat diluted apology to those 18,000 people who were long maligned at Tule Lake.

I believe that new generations of Japanese Americans now see these ancestors rightfully fighting for our civil rights when no one else would, and I believe Wayne Collins would agree that recognition of these Tule Lake “resisters” is long overdue.

So many conflicts that manifested themselves in turmoil at Tule Lake have been left untold. For example, the myth of the “disloyals” and “troublemakers” that we as a community have heard for so long needs to be more thoroughly understood and dispelled. At the same time, we also need to face the dark side of the problems created by the pro-Japan factions there. Wayne Collins provides the perfect vehicle for presenting these problems because he does not hesitate to call them out as despicable, while at the same time attributing their causes not to the inmates themselves but to the government that imprisoned them.

* * * * *

One Fighting Irishman debuts at the Japanese American National Museum on October 28, 2023, accompanied by a discussion with Sharon Yamato, Brian Niiya, and Wayne Merrill Collins. More showings are anticipated in the future.

*All photos are courtesy of Sharon Yamato

© 2023 Tamiko Nimura