This is the story of Naoharu Aihara, Isabel Stine, and Hakone Gardens—a Japanese garden located in the lush hills of Saratoga, California. Hakone Gardens, open to the public since 1966, harbors a complex history beginning with Bay Area socialite, Isabel Stine who, engulfed in a passion for everything Japanese, set out to create a miniature Japan for herself, and Naoharu Aihara, who became the master gardener and creator of this dream.

Though there is hardly any concrete information about him, his life may be reconstructed and put into the historical context of Japanese immigrants in the Bay Area. The niche job of architect and caretaker of “authentic” Japanese gardens serves as an example of how Issei managed to create a position of value for themselves in the hostile environment of anti-Asian California of the early 1900s.

Through following the few traces Aihara and Stine left behind, we can catch a glimpse at how, via world’s fairs, a North American fascination for the “exotic” Japanese culture developed in the early 1900s and how this resulted in the occupation of “Japanese gardener.”

The world’s fair, key to unravelling the story of how Aihara became entangled in Stine’s making of Hakone Gardens, is the 1915 Panama–Pacific International Exposition (PPIE). The PPIE was held in commemoration of one of the greatest accomplishments of the early 20th century and one of the most challenging engineering ventures to this date: the Panama Canal.

Under San Francisco Chronicle’s headline “San Francisco Rings Up Curtain on Her Unrivaled International Performance of Ten Months’ Continuous Gaiety” the exposition promised to transform the city from February 20 till December 4. Alongside celebrating the opening of the canal, the PPIE served as a stage for nations to showcase their accomplishments, for the U.S. to demonstrate its technological progress and for manufacturers from all over the world to present their goods. The grandeur of world’s fairs is not to be understated and we can well imagine how Isabel Stine got caught up in the excitement of the PPIE.

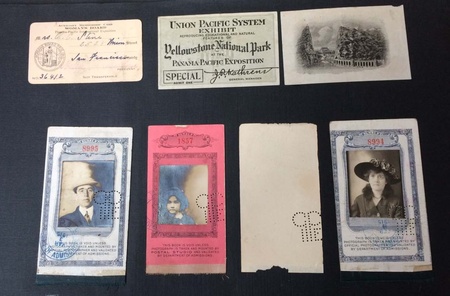

When leafing through Stine’s photo albums, recalling her impressions of the PPIE, her infatuation, especially with the Japanese exhibit, becomes evident. The albums are precious keepsakes that allow us a peek into what the exciting life of Isabel Stine looked like. We learn that Stine was a founding member of the San Francisco Opera, and in newspaper articles, she is mentioned as an author, a playwright, and a philanthropist. Furthermore, she and her husband, Oliver C. Stine, were very much involved in the PPIE: Isabel Stine was a member of the Women’s Board and, Oliver C. Stine and his company held shares in the fair. The family housed several Japanese officials and Stine collected many pamphlets and postcards, mostly of the Chinese and the Japanese exhibits, for her album.

The Japanese exhibit mentioned, received considerable newspaper coverage. “A kaleidoscope of color, variety and interest” was how the Oakland Tribune saw the Japanese contribution. This is but one example to show what a strong impression the nation of Japan managed to have on the visitors of the fair – lucky for the government-chosen curators, who spent an immense sum of money and labor. Especially the “Japan Dedication Day” held on February 24, sparked great media interest. Issei and Nisei school children, living in and around San Francisco, dressed in kimonos, handed out cherry blossoms, Japanese and American flags, and sang both national anthems. A parade with Japanese bands, athletic games, and contests as well as fireworks were held. Performers were “residents of the Japanese colonies of California, and visitors from the Orient,” said the Oakland Tribune. This is noteworthy, as the wording in all articles covering the Japanese contributions points out a clear differentiation between Westerners, the Japanese adapted to the West and the general group of “Orientals.”

So despite the Japanese government’s effort to create a positive image and to be recognized by the powerful Western nations, a certain demarcation between East and West remained. Still, over 1,500 medals and several “Grand Prizes” manifested the Japanese exhibits success at least on a material level. This must have pleased the large committee of Japanese officials present at the PPIE.

Highly intriguing here, is the fact that Stine befriended several of these officials. The Imperial Japanese Majesty’s Commissioner–General, Haruki Yamawaki, and the youngest Japanese commissioner, Sadao Yeghi, were two such acquaintances. Yeghi lived at the Stines’ for the duration of the PPIE and stayed in touch with them upon his return to Japan. Also, Stine and her husband received an invitation to celebrate the formal accession to the throne of his Imperial Majesty the Emperor of Japan, Emperor Taishō, by Consul Yasutaro Numano. These ties, together with Stine’s membership in the Women’s Board show just how deeply involved Stine was in the PPIE, with the Japanese committee and Japanese culture in general.

Regarding culture, we learn from two letters written by Yeghi that Stine adored Japanese music – she even introduced Puccini’s Opera, Madame Butterfly, to the West Coast! Its first production was (of course) held at Hakone Gardens. This appreciation for Japanese music is one of the reasons for her voyage to Japan in 1917.

Was this also the time she met with her future gardener? The time and circumstances do fit. Yet, who Stine visited and where exactly she went on her year-long trip to Japan remains unclear. Souvenirs from her trip suggest that she visited Osaka, some tea plantations and of course Fuji-Hakone-Izu National Park – as this is what she named her garden after. We do know that Stine returned to Saratoga full of ideas, furnishments and inspiration. Most likely she also met her architect Tsunematsu Shintani, and landscape designer, Naoharu Aihara when in Japan.

Construction for Stine’s dream garden began in 1917. Hakone Gardens was the family’s retreat from the city and Stine poured her entire love for Japan and fine arts into the place. Dressing up her children in luxurious kimonos and having their pictures taken professionally by the Japanese photography studio Motoyoshi of San Francisco was one of the things Stine greatly enjoyed doing.

With the purpose of bringing Japanese culture closer to the people of the Bay Area, Stine delighted in hosting social gatherings (cf. Madame Butterfly).

Sadly, Stine’s dream of Hakone Gardens was shattered when the Great Depression hit her family hard. Stine was forced to sell the estate and garden in 1932 and her entire “Oriental Collection” in 1946. The buyer of Hakone Gardens, Major Charles Lee Tilden, conscientiously continued to treat the garden and estate and stressed the “authenticity” of the Japanese garden even more painstakingly.

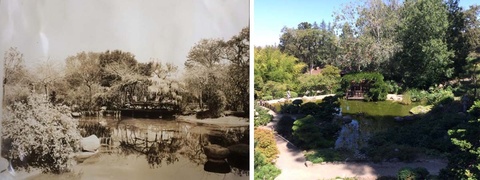

Though the layout has changed from Stine’s time until today, the concept and majority of the garden elements have stayed the same. Most changes were implemented by James Sasaki, Major Tilden’s trusted Japanese gardener, who took special care to implement “traditional” elements to the garden landscape. Comparing Stine’s photographs of the lake and the Upper and Lower Houses with Hakone Gardens today, we can see that the garden retained its signature look. Aihara’s design is very present, the general appearance is solely more aestheticized to please a public crowd.

Now, to appreciate Naoharu Aihara’s involvement in the making of Hakone Gardens, we must first understand establishment of the Japanese gardening trade in California. From 1908 to 1911 approximately 50% of Japanese immigrants to the U.S. worked in the horticultural and agricultural industries. In 1920, close to every fifth Japanese immigrant to the U.S. was employed in the gardening trade at least once. Usually, Japanese started their gardening careers by placing ads in newspapers, just like James Sasaki, Aihara’s successor, who was hired by Major Tilden after he had stumbled across Sasaki’s text.

Oftentimes the gardeners had relatives or acquaintances already in the business that took on apprentices. Less frequently gardeners were organized in little enterprises. In the early 1900s, the entire gardening business was very much a hands–on job. Hardly any gardener could afford to buy a car and most walked or cycled to work, dragging their lawn mowers along. This was also the time when the Issei and Nisei gained the reputation of having a green thumb due to their great involvement in Californian agriculture. Particularly in southern California Issei gardeners gained economic force when maintenance gardening took off in the early 1900s and was regarded as an ethnic trade in 1920. It is striking that this apparent cultural endowment along with its promotion at the world’s fairs helped create the “Japanese gardener”.

But what about the story of Naoharu Aihara? Even after various attempts to uncover details about Aihara, there are few hard facts. Known are his life dates,1870–1940, and that Aihara remained true to the gardening trends of the time. This can be judged by the careful distribution and setting of native Japanese plants, the incorporation of the surrounding landscape as well as the remnants of the scenery of the Fuji-Hakone-Izu National Park that can be detected at Hakone Gardens. In the preceding paragraphs, a frame has been constructed, wherein we can place the elusive Aihara to fathom a picture of what could have been.

Let us consider a hypothesis as to when and why Aihara came to the U.S.: Aihara came to Saratoga after Stine hired him during her trip to Japan in 1917. According to Hakone Gardens’ centennial movie, Aihara was an Imperial Gardener before Stine persuaded him to come to California. Two additional sources support the ‘Imperial tie’-theory. A 1960 article in the Oakland Tribune states that Hakone is a “garden straight from the fabled Orient, designed in fact, by a Japanese court landscape designer who had served the emperor”. A 2010 contribution to the Shared Heritage Travel Itinerary of the National Park Service claims that Aihara was “from a long line of Imperial Gardeners based in Kyōbashi, Tokyo”. Yet, I argue that that this is still rather foggy, since neither research in English nor Japanese provided further information and the Tokyo Nodai (Tokyo University of Agriculture) could find no trace of Aihara either. Perhaps Aihara already travelled to San Francisco for the Mid–Winter Fair in 1894 and helped design the Tea Garden (no sources confirm this). Or, maybe, he was in the city in 1906 and contributed to the garden-making for a Japanese art show as The San Francisco Call wrote.

Whatever his background, Aihara designed and took care of the Hakone Gardens in the early 1900s and left his traces till today. Aihara likely maintained the garden on his own and lived during a time when the Japanese garden as a “thing” was established and therewith the ‘Japanese gardener’ as a fixed term. He along with hundreds of other Issei and Nisei gardeners, had an impact on homeowners’ lives as they actively shaped part of these homes and thus how their employers lived. Aihara’s puzzle, as incomplete as it may be, allows us to glimpse into the history of a very specific group of immigrants who created a niche for themselves.

What the entangled stories of Aihara and Stine teach us, is that the past may not always be as straightforward and causal as one might assume. Who would have thought that Isabel Stine hosted Japanese officials at her San Francisco home, that she had animated correspondence about Japanese music with them and that she even wrote her own plays? Then, is it not a remarkable development that Stine met with Aihara who created, what is today called, a “genuine” Japanese garden in the middle of California? A world’s fair promoting national self–imaging, the necessity of Issei to find work, the alien exclusion regulations, Californians’ zeal for anything “exotic”, the creation of the concept of “genuine” Japanese gardens are what Isabel Stine and Naoharu Aihara combine to one story.

© 2022 Eliane Schmid