The fight of disability rights in the United States has included several Japanese-American citizens, as well as local, state, and national officials and their families. Many became involved because of personal experiences, including the mass incarceration and combat during World War II. Yet, their significant contributions to the development of the Americans with Disabilities Act has mostly been overlooked.

On February 19, 1942, six weeks after the Japanese military bombed Pearl Harbor, President Franklin Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066.1 The exclusion order forced 120,000 Japanese-Americans and their families into incarceration camps in Arizona (Poston and Gila), Arkansas (Jerome and Rohwer), California (Manzanar and Tule Lake), Wyoming (Heart Mountain), Utah (Topaz), Colorado (Amache), and Idaho (Minidoka).2

Disabled people were initially exempt from the exclusion order.3 However, in the end, except in cases of severe disability, such as Ron Hirano, Taeko Hoshida, and Toyoki Kurima, everyone else, including children, accompanied their families to camp. Taeko Hoshida and Toyoki Kurima were placed in institutions when their families were sent to camp and died there before their families returned.4 Ron Hirano was another exception. He was the only one of eleven Deaf students at the California School for the Deaf and Blind to be exempt, because his parents were afraid that his education would suffer in camp.5

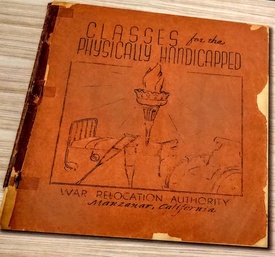

Although conditions were bleak, parents and authorities attempted to create an environment as normal as possible. Graduation ceremonies were held and schooling resumed at the assembly centers within weeks. And, after everyone was moved to permanent facilities that summer, school resumed in September. But it was almost a year before the first school for children with disabilities opened at Manzanar incarceration camp. More opened in other camps, including Tule Lake.6

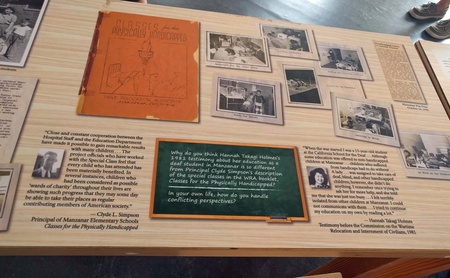

Hannah Takagi, a former student at the California School for the Deaf moved to Tule Lake with her family, hoping to get a better education than she had at Manzanar. Unfortunately, it did not work out:

“Children suffering from deafness, blindness, mental [disability], and physical paralysis were lumped into one class under the supervision of a teacher…who understood the needs of none of us. She did not even allow me to use sign language.”7

Takagi did have “one truly rewarding experience” at the school. After students decided to rename it the Helen Keller School8, Takagi wrote to Keller whose reply was published in the camp newspaper:

“I am glad of the chance that the children there have to learn to read books, speak more clearly and find sunshine among shadows. Let them only remember this-their courage in conquering obstacles will be a lamp throwing its bright rays far into other lives beside their own.”9

The Alabama Federation for the Deaf has a copy of the original and the envelope.10

In addition to disabled people entering the camps, the poor living conditions often led to babies being born with disabilities. The Matsui family was sent to Tule Lake. There, their son Robert, got an ear infection and a high fever. Years later, he learned that, because of the infection, he lost 20% of his hearing in both ears. But that was not all. Alice Matsui contracted German measles (rubella) while pregnant. The family moved to the Minidoka incarceration camp in Idaho where Barbara was born blind. However, Matsui does not believe that his conditions in the camp caused his hearing loss or his sister’s blindness. “I wouldn’t want to even speculate,” he said, explaining that those illnesses could have happened at any time in those days.11

Tama Tokuda became pregnant with her eldest child Floyd in Minidoka. Unfortunately, there was an incident in which “the camp doctor, this Caucasian guy, gave her a very powerful antibiotic for a kidney infection” resulting in Floyd being born mentally disabled.

Additionally, among the over 33,000 Japanese-Americans who served in the American military, many became disabled during combat, including Daniel Inouye and Masayuki “Spark” Matsunaga, from Hawaii. Both became disabled while fighting in Italy. Inouye lost his right arm and Matsunaga’s right leg was severely damaged.12

Notes:

1. “Executive Order 9066: Resulting in the Relocation of Japanese (1942).” General Records of the Unites States Government; Record Group 11; National Archives. Accessed June 15, 2020.

2. “Japanese-American Internment During World War II.” National Archives.

3. Final report, Japanese evacuation from the West Coast, 1942. War Relocation Authority (WRA), 1943. National Library of Medicine. p. 305. Accessed June 20, 2020.

4. Hoshida, George Y. “Life of a Japanese Immigrant Boy in Hawaii & America (Excerpts).” The Untold Story: Interment of Japanese Americans in Hawai’i. Accessed May 15, 2020.

Barbash, Fred. “Internment: The ‘Enemy’ 40 Years Ago.” Washington Post. December 5, 1982.

5. Hirano, Ronald. Ronald M. Hirano. Interview by Lu Ann Sleeper, June 6, 2013. Accessed March 29, 2020.

6. “Graduation Ceremony Impressive Education Vital Says Speaker.” Tulare News. July 11, 1942, Vol. I No. 19 edition.

“School Bell Tolls Today; Takagi.” Tulean Dispatch. September 14, 1942, Vol. III No. 51 edition.

“Classes to Help Handicapped People.” Manzanar Free Press. April 21, 1943, Vol III No. 32 edition.

“Special Students School to Open Monday at 7218.” Tulean Dispatch Daily. May 28, 1943, Vol. 1 No. 59 edition. .

7. Deaf People and World War II. “Testimony of Hannah Tomiko Holmes Read by Gerald Sato.” Accessed April 2, 2020.

8. “Helen Keller School.” The Daily Tulean Dispatch. August 16, 1943, Vol 6. No. 26 edition.

9. Deaf People and World War II. “Testimony of Hannah Tomiko Holmes Read by Gerald Sato.” Accessed April 2, 2020.

10. Keller, Helen. Letter to Hannah Takagi Takagi. “Letter from Helen Keller to Hannah Takagi about Interned Japanese Children’s Education. August 2, 1943,” August 2, 1943. Helen Keller Archive. .

11. CUNIBERTI, Betty. “Internment: Personal Voices, Powerful Choices.” Los Angeles Times. October 4, 1987.

12. “Chapter 5: Fighting for Freedom.” Order 9066. March 28, 2018. Accessed December 1, 2021.

National Park Service. “Daniel Inouye: A Japanese American Soldier’s Valor in World War II” (U.S. National Park Service). Updated November 9, 2017.

Albin Kowalewski, Asian and Pacific Islander Americans in Congress, 1900-2017 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 2018), p. 262.

*This article is a slightly expanded version of the original, published on the Disability History Association’s AllOfUs blog in November 2020 for the 30th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act.

© 2021 Selena Moon