On my refrigerator is a magnet with a reproduction of a painting called 14th Street, a colorful, angular cityscape with a view dominated by a skyscraper. I found it some time ago at the shops of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. At the time I bought the magnet, the name of the artist, Bumpei Usui, was unknown to me. I subsequently discovered that Usui was a prized member of the Nikkei artist community in 20th century New York: a master craftsman and painter whose art took from both fields.

Usui was born in Japan in February 1898. There is little reliable information on Usui’s early life. According to a 1935 profile of him in The New Yorker, he grew up on a silkworm farm in Nagano, then in 1917 moved to London, England to join his brother, an art dealer. While in England, he learned the craft of Queen Anne lacquering.

Usui arrived in the United States in 1921—he later told friends the colorful tale of entering the country illicitly by jumping off a ship and swimming to shore! Once settled in New York, he took up the trade of lacquering furniture, then at some point branched into picture framing (plus raising Siamese cats).

According to writer Heywood Hale Broun, he often advised his artist clients not to frame their paintings at all. Nevertheless, he did framing work for such well-known artists as Reginald Marsh and Yasuo Kuniyoshi. Usui and Kuniyoshi formed an enduring friendship.

As Usui established himself as a framer for artists, he decided to produce his own work, and enthusiastically took up painting as a self-taught artist. Kuniyoshi proved to be a stylistic model as well as a mentor, though Usui apparently never studied with him formally (though Usui may have studied privately with famed 'ashcan school' painter John Sloan).

Usui’s first chance to show his work came in 1922, when the Japan Times newspaper sponsored a showing by the Japanese Artists Society in New York. In the next years he remained active in Japanese community exhibitions. In 1927 he contributed to “The First Annual Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture by Japanese Artists in New York.” There Usui exhibited The Furniture Factory, which would become his signature piece. His work, an expansive view of a busy factory floor with artisans designing and constructing woodwork, arguably anticipates New Deal-era murals celebrating manual labor.

In February 1935, he joined a show of 27 New York-based “Japanese” artists, again sponsored by the Japan Times, at A.C.A. Gallery in New York. Beyond their joint shows, Usui remained close in spirit to his Issei artist colleagues. The 1930 census listed Usui as a lodger in the apartment of his dear friend Chuzo Tamotsu on East 15th st., amid a colony of Japanese artists.

Still, Usui soon expanded beyond exclusive identification with his own ethnic group. In 1925, he and four Issei colleagues exhibited their work in a large show, the Salon of the Independents, at the Anderson Galleries. Their output caused a sensation. A critic from the Daily Worker remarked facetiously, “The Exhibition has been invaded by Japanese artists who have contributed some of the best pictures of the exhibition.” The New Yorker extolled Machine Shop: “[It] is new in a way that does not remind you of every other modern you have seen this year.” In 1927, The New Yorker praised Usui’s Dawn at Hilltop, which was featured in that year’s Salon.

In 1928, 1929, and 1930, Usui again contributed pictures to the Salon, at the famed Waldorf-Astoria hotel. In 1929, Usui’s work Sunday Afternoon was reproduced in the Brooklyn Eagle. During this time, his art appeared in a show in Washington DC. Washington Post critic Ada Rainey remarked that Usui’s painting of a New York skyline, presumably 14th Street, was “painted with much distinction.”

Meanwhile, Usui entered several Salon of America exhibitions at the American-Anderson Galleries, sponsored by the College Art Association (C.A.A.). Edward Alden Jewell of the New York Times described Usui’s painting in the 1931 show as a “striking work.” In a review of the 1932 show, Ralph Flint stated in Art News that Usui, “has one of his best efforts here in By the Window.” Henry McBride proclaimed in the Baltimore Sun that it was one of the few good works shown. After that, the C.A.A. sent the 1932 show on a national tour. In 1933, the show played at the Albright Art Gallery in Buffalo, New York. A critic from Art News lauded Kuniyoshi, Tamotsu, and Usui’s works for their “linear, almost stringy, handling of color.”

In 1935, Usui’s work was featured in the C.A.A. touring show Modern Americans. When Modern Americans was exhibited at Williams College, the school newspaper Williams Record recorded, “[Usui] has found time to teach himself art with such amazing results that art patrons and critics in New York are at present convincing themselves that…they have made an important find.”

As his renown increased, Usui joined several shows. For example, in 1932 he was a guest artist in a show, Little International Exhibition, produced by the art cooperative An American Group at the Barbizon-Plaza Hotel. During this period, art enthusiast Robert U. Godsoe launched a “neighborhood exhibitions” project to display art in hotels, bookshops, restaurants and theater lobbies around the city. Usui joined Godsoe’s neighborhood shows at the Gotham Book Mart in Manhattan and the Towers Hotel in Brooklyn, plus a Godsoe show at the Hotel Roosevelt, “From Realism to Surrealism.”

In October 1934 Usui was included in a show at Wanamaker’s New York department store. His work, entitled variously Painting and Interior, is a view of an apartment with a large vase of flowers foregrounded. It was praised by Edward Alden Jewell in the New York Times, and reproduced in its pages, and was thereafter bought by a patron for $200—Usui’s first art sale!

It was in this period, despite the rigors of the Depression, that Usui earned his greatest renown. In March 1934, he was one of 120 artists from the annual Washington Square Art show who were invited to contribute to a show at New York’s Roerich Museum. A jury (which included Kuniyoshi) awarded five of the artists, including Usui, a prize consisting of an invitation to mount a one-man show at the Museum. When Usui’s painting show opened the following month, New York Herald Tribune critic Carlyle Burrows noted the resemblance to Kuniyoshi’s work but praised Usui’s “charming” works as showing “a nice feeling for design.”

In January 1935, Usui was profiled in an article in The New Yorker, which described him as a prize framer and artist. However, even with such publicity, neither framing work nor private art sales were enough to sustain him financially. Instead, he was hired by the New Deal-era Works Progress Administration (WPA) to produce artwork for its Federal Art Project (FAP). In 1935, Usui’s painting Coal Barges was featured in a show of FAP artists at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and reproduced in the catalogue New Horizons in American Art. Soon after, Usui’s art (presumably his still life of flowers, Dahlias) was included in an FAP show organized at the New School for Social Research.

Following these shows, the FAP arranged art tours across the United States. In the process, Usui gained a national profile. In early 1938, Coal Barge won a prize at the Annual Exhibition at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. In-mid 1938, Dahlias was included in a show at the FAP Gallery in Chicago, then another at the de Young Museum in San Francisco. In 1940 an Usui work (presumably Dahlias) was shown in the American Art Today Pavilion at the New York World’s Fair, and was then featured in a pair of shows at WPA-created museums in North Carolina. Usui’s art was included in another WPA show that toured the Western states during 1941. When it was shown in Utah, a critic for the Ogden Standard-Examiner commented: “[H]is clean use of color, and delicate linear treatment of objects indicate the ability to work with a real economy of means.”

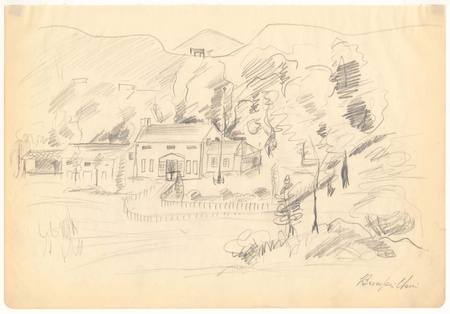

With the coming of World War II, Usui (like his friend Kuniyoshi) was brutally displaced from his status as an admired and accomplished American artist, and relegated to the status of “foreigner.” While he was not rounded up by the U.S. government, he was questioned on multiple occasions by FBI agents, and was forced to ask friends to hide his large collection of Japanese swords. He seems to have largely abandoned painting for a time. Later he stayed at Kuniyoshi's house in Woodstock, NY and painted many pictures.

Unlike Kuniyoshi and Isamu Noguchi, he did not join antifascist groups such as the Arts Council of the Japanese American Committee for Democracy. Once the war ended, Usui was one of 20 artists who organized a Benefit Dance for the Greater New York Committee for Japanese Americans. In May 1947 Usui participated in another Japanese Artists Show, at New York’s Riverside Museum.

In 1947, Usui held a one-person show at Laurel Gallery in New York City. It was the first time in 10 years that he had exhibited new art. Critic H.D., writing in the New York Times, praised Usui’s work Shanties in the Bronx and his paintings of Kuniyoshi’s house in Woodstock. (The critic also praised Usui for framing his own canvases). The Herald Tribune described the flower studies and landscapes as quite American, but having “delicate touches that remind one that Usui is a Japanese.” In Art Digest, J.K. R. lauded Acorn Squash and Camels (Cigarettes) for their “sensitive brushwork [and] nice feeling for color and gracious handling.”

Despite such reviews, Usui largely withdrew from painting after 1949. Along with the artist Frances Ritter, whom he married in 1954, he settled into his frame business and also collected Mexican figurines and Japanese swords—alongside other devotees he founded the Japanese Sword Society.

In 1977 he suffered a double loss. First, his shop on West 17th Street was robbed. Soon after, a group of thieves, passing themselves off as police officers investigating the earlier crime, entered Usui’s Greenwich Village home and robbed him and his wife at gunpoint of collections of samurai swords and Asian antiques. The loss was a reported $300,000. (Shortly afterward, Usui auctioned off parts of his remaining collections—one antique sword alone sold for $13,000).

Usui continued to show his art in galleries. In early 1979 his Portrait of Yasuo Kuniyoshi, an affectionate look at the artist reclining casually in a chair and smoking a pipe, was included in a show of New York Japanese artists at Azuma, then reproduced in Art in America magazine. Soon after, a show of his paintings, Bumpei Usui: paintings 1925-1949, opened at the Salander Galleries in New York. In 1983 he was honored with a show in Japan, Bumpei Usui: American Scene, 1920s-1940s at the Fuji Television Gallery in Tokyo.

Bumpei Usui died in New York in March 1994. By the time of his death, his fame had been obscured, and only a few local galleries continued to feature works of his. In 2013 the Metropolitan Museum purchased The Furniture Factory, making it Usui’s first canvas in a New York public collection. The following year, the painting was featured in the Metropolitan’s show Reimagining Modernism: 1900-1950. It garnered significant attention. Randy Kennedy of the New York Times explained, “The painting shows the floor of a factory, probably somewhere in the city, packed with workers, many of them probably Japanese-American, making what looks like bland furnishings for the frothy American middle class.”

Another show at the Metropolitan featured 14th Street (on loan from the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts)—from which my refrigerator magnet stemmed. The Smithsonian Museum of American Art, which owned Usui’s Dahlias and his Portrait of Yasuo Kuniyoshi, began displaying them regularly. Usui’s career also became the objects of increased interest in Japan. Party on the Roof, featured in the collection of the Nagano Prefectural Shinano Art Museum, has much studied in recent years. The renewed interest provides new perspectives on Usui’s remarkable art.

© 2021 Greg Robinson