Thirty years is half a life. This is what happens in the story of the Peruvians who one day decided to go to Japan, without much more than their desire to work and hope for a better near future. Some of these senpai (more experienced people) in the community remember those early days.

No one would have imagined that a temporary stay to earn money would end up lasting and making them put down roots. Some left Peru single and today are grandparents; Many began their youth when they boarded the plane and today they have gray hair. Thirty years later, there are up to four generations of Peruvians in Japan.

“We were surprised that they arrived suddenly and in large numbers. 'What is happening?', we asked ourselves at work. "That meant that things there (in Peru) were worse than usual," recalls Don Luis Oshiro, a jovial Peruvian who has already surpassed retirement age, but whose vigor and enthusiasm allow him to continue being one of the most senior officials. experience in the glass factory where he has worked since 1983.

It predates the so-called “Dekasegi Phenomenon ” (a term that refers to temporary work outside the place of origin). He arrived in Okinawa in 1980 and from there he enrolled in jobs in Fukui and Shizuoka, ending up in Kanagawa, in the city of Kawasaki, where he lives. But he did not do it as a group, as would happen a decade later. He came on his own, to try his luck, and stayed.

Oshiro and other “veteran” Peruvians instructed the first dekasegi – as they were then baptized – in the tasks to be carried out in that subsidiary of Asahi Garasu and in the routine of life in Japan.

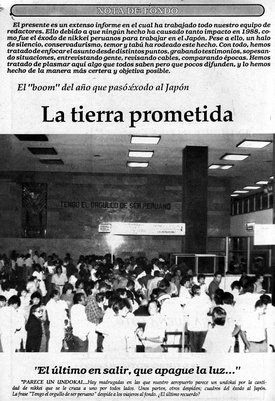

February 1989 is indicated as the date on which the mass exodus of Latin Americans to Japan would have begun. This means, in large groups, organized and previously accepted by Japanese contracting companies.

They traveled through tourism agencies, many of which sold tickets with financing. Days when Peru broke the world record for inflation and terrorism seemed to win the battle in many places in the country. Enough to seek a future outside their borders, becoming “economic exiles.”

In the mid-80s, Peruvians in all of Japan did not reach a thousand. 1989 would end with a number greater than 4 thousand, almost all of them arriving in the last few months to work. With family visit visas, those who had contact with their Japanese relatives. Those who don't, with “technical training” visas that the government invented to cover the thousands of vacancies in the Japanese productive machinery. There was still work, but the end of the boom of the “bubble economy” era was just around the corner.

TOCHIGI AND KANAGAWA: THE BEGINNING

Mooka in Tochigi, and Kawasaki in Kanagawa, were probably the cities in which many of these “pioneers” spent their first night in Japan. They were the next stops after landing at Narita airport.

The first was the headquarters of the Naruse or Narukawa agency, which became, in the late 80s and much of the 90s, the largest contractor that hired Latin Americans. There, only in the Kinugawa Gomu plant (which supplies auto parts to Nissan), it located about 300 of its workers, outside of other factories that make up the industrial complexes of this small town.

They arrived at the contractor's accommodation several times a week, and from there they were sent to different prefectures. Before the arrival of Latin Americans, in 1988, only 134 foreigners lived in Mooka.

In Kawasaki, Kanagawa, factories related to Asahi Garasu, Isuzu, Furukawa or Press Kogyo, among others, met the salary expectations of thousands of others. In exchange for this, long hours handling machines for the first time in extreme conditions and temperatures, in many cases. It was in this city where many gathered, given that the companies that sent remittances, Peruvian restaurants and several contractors were located there. It would also be the birthplace of the formation of some Peruvian associations.

ALIENS HERE AND THERE

Marcos Kanashiro arrived at the age of 20, in March 1989. He was one of the five cousins that an uncle called to work at the Hino truck factory, in the city of Hamura (Tokyo). He went first to Okinawa, from where, via Hello Work – the national job search agency – they extended a contract for six months, at the end of which he had to return.

“At the beginning there were many shocks: the time change from day to night, the food, the little knowledge of the language. My job was to weld for several hours, which ended up damaging my eyesight. In order to sleep I had to put a cold towel on my forehead. I worked for a year and moved to Kanagawa, joining the Kogyo Press in Fujisawa, also to weld parts of trucks that arrived at my sector every three minutes, on the production line,” he recalls.

The majority of the workers were of Japanese ancestry and this particularity favored them after a change in immigration laws in the spring of 1990, allowing unrestricted work activities for foreigners of Japanese origin up to the third generation (sansei) for prolonged periods. The visa did not have to be renewed every six months.

But being Nikkei in Japan does not always represent the same as being Nikkei in Peru. In the experience of many, this did not increase any bonus, it did not give “extra bonus”. To the average Japanese, they might have similar ancestors, surnames, and even appearance, which might arouse some kind of sympathy, but they were still foreigners. This had consequences for some, who came to question what their true identity was.

"Actually it wasn't a shock, but one sometimes thought: 'Wow, in Peru they call me Japanese, and here I'm a foreigner.' I think everyone has felt it. But it didn't bother me because the Japanese value you for your work performance. Once you learned, the treatment was different, it changed completely. Of course, there is never a shortage of people who don't like foreigners. But compared to 30 years ago, I can say that the Japanese are already getting used to it,” says Kanashiro.

Mary Arakaki, who had also spent three decades in Japan, thought that because she was a Nikkei, the treatment of the Japanese could be different. “It was disappointing at first. There they made us feel like foreigners and here too. I always try to explain it to the Japanese. At first it was difficult, one noticed that because I was a foreigner the treatment was rough. Now are different times, they are already adapting to the changes.”

THE LANGUAGE, PENDING TASK

“I remember that when I arrived I didn't understand anything, even though I had studied some nihongo (Japanese language) in Lima. So to explain to me the work I had to do or where to go, the Japanese woman in charge would pull me by my clothes. It was something that bothered me a lot and several times I came out crying, wanting to quit. But as you learn the language, things become easier. I already understood what they were telling me and the treatment was different, with respect. It wasn't that they wanted to make me ijime (harassment or bullying ), but that, not understanding, helplessly, they felt the need to pull my apron to tell me what I should do. I think that before we had more interest in studying the language. I had to do it since my children started school because I didn't understand what they said to me in daycare or in the hospital. We had to learn by force with a private teacher,” says Gloria Zukeran, who arrived in December 1989, called by her husband, who had preceded her by a few months.

Working alongside a boss who only uses insults to point out mistakes is an experience that everyone has. This, added to loneliness and culture shock, can be a dangerous cocktail.

“Between enduring the screams and not being able to give explanations because you don't know the language, you become stressed. Not everyone has the patience to take it lightly, forget about it and move on. It affected many seriously. But in most cases they are misunderstandings or impotence, motivated by lack of knowledge of the language. In those days, the Japanese were not used to interacting with foreigners either,” recalls Marcos Kanashiro.

* This article is published thanks to the agreement between the Peruvian Japanese Association (APJ) and the Discover Nikkei Project. Article originally published in Kyodai Magazine , adapted for Kaikan magazine No. 119 and for Discover Nikkei.

© 2019 Texto y fotos: Eduardo Azato