Have you ever seen the haiku that goes, "Here are many mountains and rivers, where love and life lie?" This is the work on a stone monument located just to the left after entering the Japanese garden, at the foot of Osaka Bridge on Galvao Bueno Street in the Liberdade district of São Paulo.

Those who frequented Oriental Town, fell in love so passionately that their hearts burned, and suffered such painful experiences that they almost took their lives, felt that this was a kind of hometown, even though it was a foreign land -- such feelings are expressed in this phrase. Isn't this a famous phrase that applies not only to Oriental Town, but to all immigrant areas and colonies?

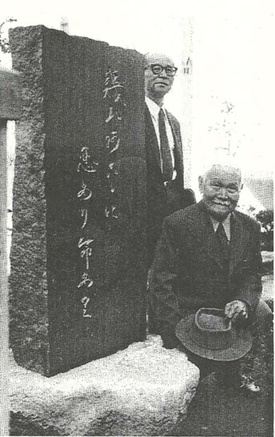

However, I had wondered why the author's name on the monument looked like it had been engraved recently. Then, this weekend, I accidentally discovered the reason. I was shocked to see that the name was not engraved on the monument in a photo of the monument published in Ando Mamon's senryu collection "Manji" (1997, edited by Kuroda Shiranui).

Moreover, on page 10, the editor writes, "Although the author is unknown, as the author writes, it was erected with the permission of the Toyogai Development Committee chairman and is undoubtedly the work of Ando Mamon. It will continue to shine with immortality along with the history of Colonia Senryu."

Mamon himself also wrote on page 7, "The area was designated as Oriental Town by the city hall, based on Galvão Bueno Street, and various facilities appropriate to this designation were being constructed, but it was decided that the vacant lot beside Osaka Bridge would be turned into a Japanese garden, and he proposed to take charge of all of the trees necessary to create the garden. Ishiyama Hakuto agreed, as a condition, that a haiku monument be erected in the garden. He was so enthusiastic that he immediately asked Mamon to choose a haiku, and he silently promised not to cause any trouble to anyone else. He immediately submitted the haiku "Iku Sangawa" ("Many Mountains and Rivers"), and with the approval of the chairman of the Oriental Town Development Committee, the monument was erected, so the absence of a haiku author was not an issue from the start."

In other words, Ishiyama Hakuto, who was entrusted with the construction of a Japanese garden, accepted the job on the condition that a haiku monument be erected, and immediately asked Mamon to select a work. Mamon, fearing that the construction of his haiku monument in such a prominent location would cause a stir in the senryu world, accepted the job on the condition that he remain anonymous. Since then, the poems have remained anonymous, but when Mamon was 91 years old, Kuroda Shiranui compiled a collection of haiku, and they were finally made public in 1997. The author's name was probably inscribed after that. So that's the only new part.

This made me wonder, when was this Japanese garden created?

According to Liberdade (published by the same chamber of commerce in 1996), the process of establishing a sister city relationship between São Paulo and Osaka began in 1969, and the city of São Paulo recognized Liberdade as an "Oriental town" under the concept of making Liberdade "Little Tokyo." The first Oriental festival, a Bon Odori dance, was held in November of the same year. According to the book, the Liberdade Square, where the festival was held, was "a park with many trees at the time."

In this trend, the Galvon Street overpass was named "Osaka Bridge" in 1970. The city's tourist bureau recommended renovating the streets to have a Japanese feel, and in 1973 Galvon Street was built as a Japanese garden. In other words, Mamon was an "unknown reader" for 24 years from 1973 to 1997, and only revealed it at the very end of his life. He was a modest man.

Mamon's real name was Zenbei. He was born in Nichinan, Miyazaki Prefecture in 1906 and came to Brazil on the Kamakura Maru in 1927. In 1931, while working as a colono on a coffee plantation, he came across the senryu poems of Kenkabo Inoue in the Japanese magazine Kaizo and became captivated. He began submitting his poems to the senryu column of Agriculture Brazil, the only magazine of its kind at the time. As a farmer, he probably added the kanji characters "魔門" to Mamon.

After the war, in 1950, they formed the Brazil Senryu Society and were among the founding members who launched the journal Brazil Senryu. In 1953, they held the first All-Brazil Senryu Competition, which continues to this day, with the 65th competition scheduled for September 15th this year.

When one reads through his collection of haiku, one finds many profound works. Only those who have experienced rock bottom could write poems such as "I jumped off and saw that there is a way of life here too" and "The spring wind caresses my raised palms." Even in a place where a family member has died, if the land becomes barren, one has no choice but to move. Poems expressing such painful feelings include "Cultivating land with no way to protect even one grave" and "Singing the national anthem makes me cry in this foreign country" that truly capture the feelings of immigrants.

Another poem about the Oriental Town was, "The smell of miso flows through this Japanese town." But the depth of the opening line is exceptional. When the monument was erected, Mamon was 67 years old and should have been a dignified senryu poet, recognized by both himself and others. But he maintained that the reader was anonymous. This anecdote gives a sense of the sophistication of senryu poets.

The activities of Japanese immigrants are quietly memorialized here and there in Liberdade. June 18th was the 110th anniversary of immigration. There is only one month left until the 110th anniversary ceremony. With the 150th anniversary of immigration in mind, I would like to approach the day while thinking about what we should do now.

*This article is reprinted from the Nikkei Shimbun (June 19, 2018).

© 2018 Masayuki Fukasawa / Nikkey Shimbun