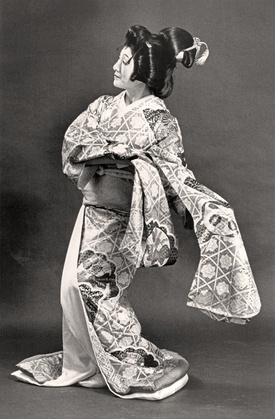

At 93, legendary dance instructor Sahomi Tachibana remains at the center of Portland’s classical Japanese arts.

PORTLAND — The years have understandably caught up with Sahomi Tachibana—she last performed on stage in 2005. The hearing isn’t as keen as it used to be, the steps are a little slower, but she’s hardly disappeared from the world of classical Japanese arts in the greater Portland area.

“Sometimes I think that after I quit, nobody else will be here to do these things in my place,” she said. “My students don’t want me to quit, most have their own things to do, but many of them want to keep dancing.”

The 93-year-old dance instructor reclined in an easy chair a few steps away from the dance studio in her Portland home earlier this month, chatting about her life and art, more than eight decades of Japanese classical dance, and the annual mochitsuki event happening this Sunday (January 28, 2018) at Portland State University.

Born Doris Haruno Abey (the y added to aid pronunciation) in 1924, dance has been a defining part of her life since early childhood in Mountain View, California. Her family were active in local kabuki theater, and she first took to the stage at age seven.

“There was a Buddhist minister from San Jose who taught children’s dances and Bon odori at our temple, and he told my mother, ‘This child is talented,’ but there was no one in Mountain View to teach classical dance,” she recalled.

The decision was made to send young Doris to live with her grandparents in the northern Japan town of Fukushima, where she spent the next three years going to school and learning to dance. She returned as a teenager, taught Japanese dance for a summer in Oakland, but went back to Japan to continue her training. The impending war, however, brought her home.

When the order was given to evacuate and detain all persons of Japanese ancestry on the West Coast in 1942, the Abey family was sent to the internment camp at Tule Lake in California’s Siskiyou County. The confinement did little to deter Doris, now with years of training under her obi, from using her knowledge to help bring some vestige of normal life to the kids in camp.

“There was no teacher at camp, so I went from being the student to being the teacher,” she explained.

After being transferred to the relocation center at Topaz in Utah, Abey’s family was lucky enough to be released so that her father could take a job offer in New Hope, PA.

“I needed to have some kind of job, but I didn’t know how to do anything, so I got a job as a cook—even though I didn’t know how to cook. I learned fast,” she joked.

With her $20 weekly salary, she continued to study, taking ballet lessons. It was during a 1948 trip to New York City that she discovered La Meri’s Ethnological Dance Center, a group that brought performances from around the world to stages in the Big Apple.

Because of her studies in Japan under Saho Tachibana, she had become the dancer Sahomi Tachibana, the name under which she is most widely known today. With few New York performers trained in Japanese classical arts, she had little support staff and coordinated all her wardrobe and makeup herself.

In 1954, she took a role as the featured Japanese dancer in Cherry Blossom Time at New York’s famed Radio City Music Hall. With a full orchestra and the legendary Rockettes sharing the stage, Tachibana played both male and female roles.

After a not-so-smooth attempt to help choreograph steps for Tallulah Bankhead for a traveling production of a Tennessee Williams play, Tachibana was hired to teach students for a production of Madame Butterfly. After one performer suffered an injury, Tachibana stepped in and was once again on stage.

Following numerous performances in and around New York, Tachibana joined forces with a Japanese producer who wanted to assemble a touring company of Japanese dancers. With this group, Tachibana performed coast to coast for thousands, particularly at college campuses.

After decades of performing, Tachibana and her husband, New York native Frank Hrubant, decided to leave the chilly weather and move west, settling near their daughter in Portland.

Since then, Tachibana has instructed countless students, has been active in local dance and cultural events, and has become the defining local authority in classical Japanese arts.

A photo of Tachibana, in full performance kimono, accompanies a section on Japanese American internment in a textbook used in Oregon schools, and she was featured in Shirley Kazuyo Muramoto-Wong’s comprehensive 2014 documentary Hidden Legacy: Japanese Traditional Performing Arts in the World War II Internment Camps.

She received Japan’s Foreign Minister Award in 2004, before giving her last public performance the following year. Her reputation continues to have long reach, as she was sought by Portland animation studio Laika to choreograph dance movements for their Oscar-nominated 2016 film Kubo and the Two Strings.

While she teaches only occasionally these days, Tachibana is still quite active in the community, and will help coordinate the dancing at this Sunday’s mochitsuki.

“The program is very elaborate at Portland State University, with ikebana, martial arts, koto, and tea ceremony,” explained Tachibana, who has never trained an apprentice to succeed her.

“Little by little, you fear these things might disappear, but somehow, I think it’ll continue.”

*This article was originally published on The Rafu Shimpo on January 25, 2018.

© 2018 The Rafu Shimpo