“I wish you had shared more about your Japanese-American grandmother’s story.” – Professor Anderson

In the fall of my freshman year in college, I took a class called Growing Up Ethnic and Multicultural. The final project for the course was to share your life story.

Excited to share what I felt was my unique life story at age 17, I wrote fifteen pages about what it was like to grow up as an Asian-American in Ukiah, a small, rural town in Northern California. I talked about the cringe-inducing “no, but where are you really from?”, and the time when a boy on the playground asked if I was Mexican because there simply weren’t that many Asian kids in our town. I talked about my love for singing and musical theater and always wishing there were more shows featuring people who looked like me (where was George Takei’s Allegiance when I was in high school?).

And then of course there was family. I talked about my parents and what it was like growing up with a Japanese-American mom and a Chinese-American dad. I talked about my Yin Yin and the important role food played in our relationship given her limited English and my non-existent Cantonese. I talked about my Ya Ya and the laundry business his parents owned in Carson City, Nevada when they arrived in America in the early 1900s. And I spent quite a bit of time proudly talking about my Ojīchan who had been drafted by the US Army during WWII before the attack on Pearl Harbor, and who would later go on to serve as a paratrooper in Europe. In the report, I included a picture of him in his military uniform and parachute pack—a lone Japanese-American in a sea of white servicemen.

In a small blip, I mentioned my Obāchan was interned in a relocation camp in Arkansas.

Almost fifteen years since taking that class, I recently came across this report as I was going through old documents. Upon reading the handwritten comment from my professor, I was somewhat alarmed. Why hadn’t I spent more time sharing Obāchan’s story?

Earlier this year, my Obāchan passed away at the age of 96, and I’ve been reflecting a lot on the full life she lived and how much she’s meant to me as her granddaughter and as a Yonsei. In memory of Obāchan, there is more I want to add to my life story about her.

So, Professor Anderson, this is what I’m adding:

The truth about why I didn’t include much about my Obāchan’s time in the Japanese internment camp is that, at the time, I didn’t know much about that part of her life. Like many niseis of her generation, Obāchan didn’t dwell much on her time at “camp”. And it was only when I was much older that I learned that it was with the reparations from the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which apologized for the internment of people of Japanese descent and provided compensation for the injustice, that my Obāchan had been able to take me and my family on my first trip to Japan when I was eight.

But there were so many other things I did know about her.

What I knew about my Obāchan is that you could always hear her before you saw her. My earliest memories of Obāchan include ringing her doorbell and hearing the musical lilt in her voice, “be right there!” She had a spirit that lifted you and a voice that carried. Growing up, people who knew her would always describe to me the beauty of her singing voice, particularly when they found out I also loved singing. Hers was a voice everyone recognized, and it could be heard up in the front row at Senshin Buddhist Temple even when she was singing in the back pews. In many ways, I grew up understanding that perhaps my love for singing was not something unique to me but simply something passed down from my Obāchan.

The other thing I knew about Obāchan was the clarity of her love. Her deep Buddhist faith filled her with meaning and community. Every Sunday, she would head off to temple--often one to pick up friends on her way even into her older years. Over the years, so many people have come up to me to share just how much of a pillar she was to this community—as a teacher and friend—and I know in return each of them played a special role in her heart. She cared deeply for others with a kindness and thoughtfulness displayed with action verbs—a reliable enthusiastic greeting, a knowing hug or phone call, an organized trip with friends, a handwritten letter just to let you know she was thinking about you.

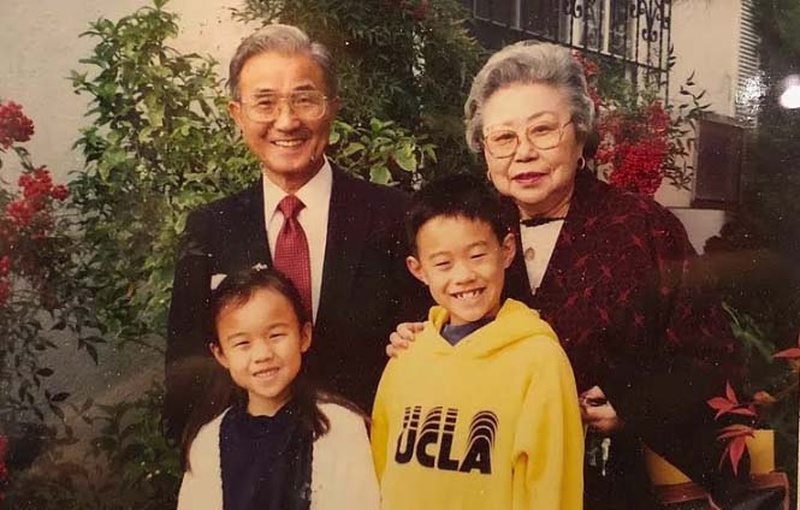

And there was no question of her love for her family. Her joyful vibrancy was the perfect complement to the calm serenity of my Ojīchan, and their love for each other was unquestionable. Similarly, she loved my mom and uncle with a strong sense of conviction. As her granddaughter, perhaps the most important thing I knew about my Obāchan was the cheerfulness and steadiness of her love.

At the time I wrote my “life story”—now almost fifteen years ago—Obāchan was exhibiting signs of dementia, which progressed steadily and mercilessly. Watching her age has been a defining life lesson in, well, life. The vibrancy with which she lived her life lays in sharp contrast to the last years of her life, slowly and unceremoniously stripped of the ability to voluntarily move or communicate.

As dementia took hold of her, her lively conversations diminished and her stories no longer filled a room. The void invited questions but she no longer had answers. With each unanswered question, another question would come to me with an urgency one can associate with pending loss. There may be something poetic about my Obāchan’s cognitive decline marking my increased interest and awareness about my family history but all it marked for me was that I missed her.

A few years back, my mom took me to Stockton, California where Obāchan spent her childhood. Walking the halls of Stockton Buddhist Temple, I found myself staring back at a picture of Obāchan as a pre-teen in a choir picture, and then again in many other photos still preserved after all these years. Shortly after visiting Stockton, we continued tracing Obāchan’s steps to Rohwer, Arkansas, where she was incarcerated during WWII. As we watched an informational video about the camp at the WWII Japanese American Internment Museum, I saw my great-grandfather in the old footage. It didn’t take me long to find Obāchan, too, on the walls, many times in pictures I had never seen before. The range of emotions I experienced exceeds that which can be described here but there was a strong mix of sadness, anger, and discovery.

Never before had a museum’s role in preservation ever been as important to me, having preserved a glimpse into a part of her life I had not known well. Out of curiosity, I googled her afterwards. There I found her again in articles preserved in the Library of Congress from the local camp newsletter—involved in organizing a talk on Buddhism, MC'ing and singing at a social event, and playing out other vignettes of what daily life was like in camp.

A few weeks after her passing, my husband and I decided at the last minute to visit a small exhibit at the San Francisco Presidio Officers’ Club about its role in WWII and the Japanese American incarceration. Obāchan wasn’t rounded up in San Francisco so I didn’t expect to see her there–but as I looked closer at the windows, I realized all 120,000+ names of those wrongfully incarcerated were etched in each pane, including Elso Kazuko Ito, my Obāchan.

Incarceration was just one part of her life but somehow unexpectedly seeing her name in the window felt like a sign—while there is a sadness and finality in her passing, I still see her. Maybe explicitly in this case, and more subtly in others—in mannerisms my mom has adopted from her, or in my uncle's shared love of her favorite operas, in my brother's hilarious re-enactments of some of our favorite childhood memories of her, or whenever I tell my husband how much he would have enjoyed getting to know her (and watching Lakers games together). A sign that her story lives on through all the lives she touched, including mine.

There are things I know about Obāchan from my lived memories with her and the things she shared. In these past years retracing parts of her life, there are also things I know now from parts of her life she didn’t share. Together, what I’ve known and what I’m still learning serve to paint an even more vibrant and nuanced picture of Obāchan. And the more I discover about her journey, the more I continue to define my own life story.

© 2018 Jessica Huey