“Japan is such a small island country…. What is the use of returning to such a place? If we have to fulfill our filial duty to parents and live with wives, why don’t we have them come to America? If the difference in the language and customs bothers us, why don’t we learn to adapt to them”1

Masuo Yasui

The rapid development of Japanese farm communities in Oregon was marked by the emergence of families. The early Japanese immigrant society was primarily a world of young bachelors. During the 1910s, the migratory nature of the community changed as more and more immigrants established their own families. As an unexpected consequence of the 1907-1908 Gentlemen’s Agreement between Japan and the United States, there was a massive influx of Japanese women, including “picture brides.”2 Between 1910 and 1920, the Japanese female population in Oregon rose approximately five-fold from 294 to 1,349. The newly-established couples were the foundation of Japanese farming settlements. In Hood River, for instance, most of the Issei farmers were married by 1920, making the male-female ratio four-to-three in the community.3

The Japanese immigrant family in Oregon was a microcosm of new sociocultural forms that emerged in the process of Japanese adaptation to Oregon society. Like other immigrants, the Issei brought their culture and traditions from Japan, but upon settling in Oregon they began to adapt to the new environment. Some cultural elements were discarded while others were reinterpreted and renegotiated in response to the changing realities of life in America and the changing definition of what it meant to be Japanese in Oregon.

One new sociocultural form was evident in the changing definition of gender roles in Japanese immigrant families. In Oregon, the Issei wives played multiple roles, breaking out of the confinement of traditional subordination. Not only did they take charge of domestic chores and child rearing, but they also played an indispensable part in the family economy. An Issei woman recalled those days:

Helping my husband, I worked so hard that I was amazed at myself. If we did not work hard, we couldn’t go on living. When my husband failed in his business, I worked all the harder in order to help him start again. I drove a car around all over in order to buy several hundred dollars’ worth of farm tools.4

An Issei man also described the hard work of the women with admiration:

When harvest season began, housewives got up at 5 a.m., fixed breakfast and looked after the horses. At 7 o’clock wives and husbands went to the orchards. They worked until 6 p.m. for twelve hours a day, except for one hour at lunch, day after day. Especially wives worked like plough horses, and even after dinner they worked with their husbands, boxing the fruit. Then after everyone else was in bed, they cleaned up and put things in order. For about a week every year they slept by their husbands in bed without even taking off their shoes, just cat-napping.5

Likewise, the men took on tasks that they would never have done in Japan. Since the delivery of a baby cost $20 to $50, many Issei husbands acted as midwives for their wives. One man remembered how he learned the necessary techniques of delivering babies from simple medical books. One veteran delivered as many as eight babies by himself.6

Mutual support was the new social norm on which Japanese immigrants built their families, communities, and industries. Commercial and agricultural alliances, as well as individual diligence and persistence, were the best resources that the Issei had to achieve social and economic advancement in Oregon. In Portland, Japanese merchants formed the Hotel Owners’ Union, the Grocery Association, and the Laundry Union. Complying with the regulations and labor conditions set by the mainstream unions, these Japanese maintained good relations with the white business community, which promoted a favorable commercial environment in Portland.7

Issei farmers organized cooperative organizations which assumed a variety of roles ranging from supplying farm necessities to financing loans and from packing to collective marketing.8 In the Portland vicinity, Hood River, and Lake Labish, a number of Japanese growers’ guilds were formed specializing in the production of cauliflower, green peas, strawberries, celery, and asparagus. Based on mutual cooperation, Japanese farmers produced 90 percent of the state’s cauliflower and broccoli, 75 percent of the celery, 60 percent of the green peas, and 45 percent of the asparagus by 1941.9

Community institutions constituted another layer of sociocultural evolution in Japanese immigrant society. In order to meet the needs of the Issei, many organizations appeared within Japanese communities. They provided the residents with vital services ranging from administrative to religious and recreational to economic. First and most importantly, each Japanese settlement had a Japanese association.10 The Japanese Association of Oregon in Portland functioned as a central organization, encompassing a number of local associations in Oregon, Idaho, and Wyoming. In a sense, the network of local associations around this central body was the basis of community identity and solidarity among the Oregon Japanese. The network also enabled the associations to become the community spokespersons, representing the best interests of the immigrants to the dominant society and even to the Japanese government.

The Japanese associations were crucial in the everyday life of the Issei. Under the Gentlemen’s Agreement, if an immigrant wanted to re-enter the country and/or to summon his family members, he had to prove, with an official certificate issued by the Japanese Consulate, that he was a bona fide resident who had been in the United States prior to 1908. To obtain a certificate, the immigrant applied to his local association. After checking the applicant’s data, the association endorsed the application before the Japanese Consulate in Portland issued the appropriate certificate.11 In the same way, local Japanese associations helped Issei men obtain the certificates they needed to defer Japanese military service every year.

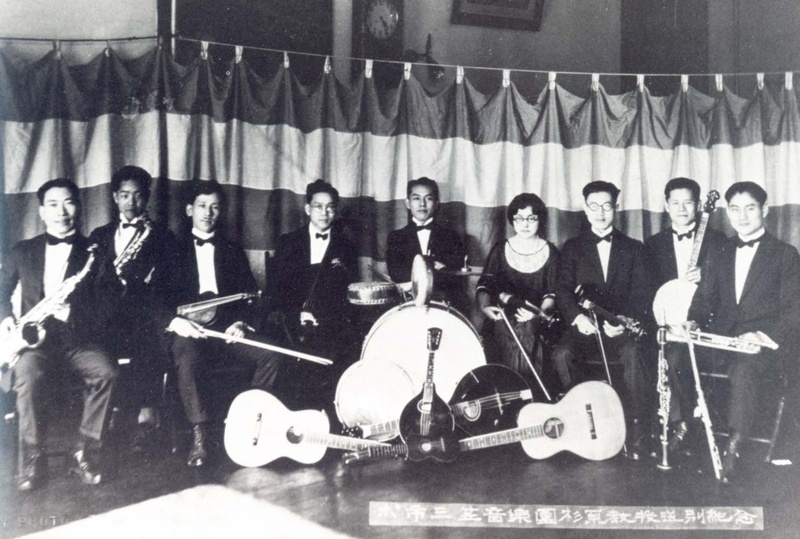

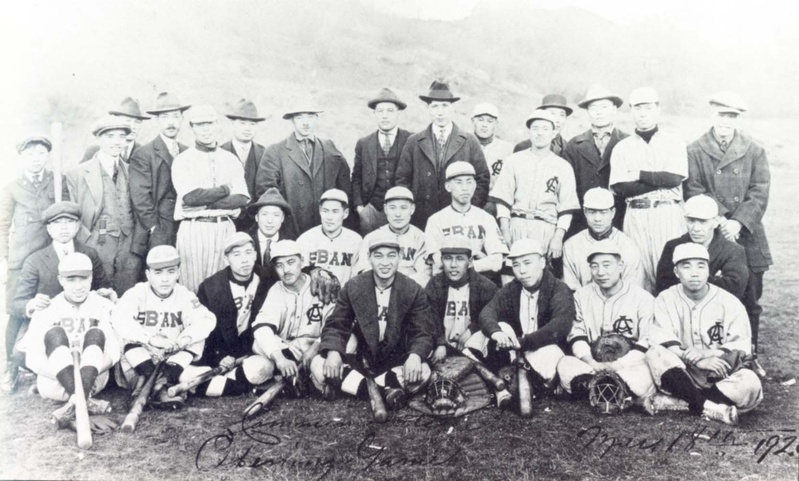

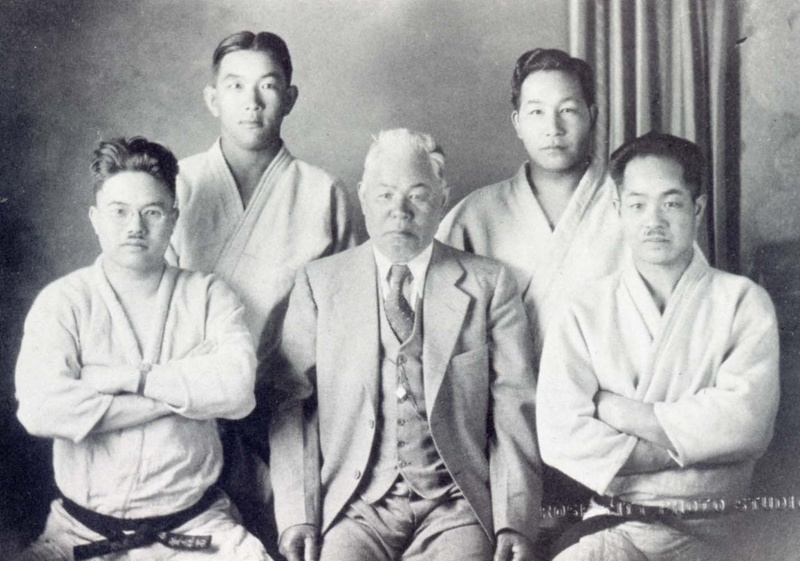

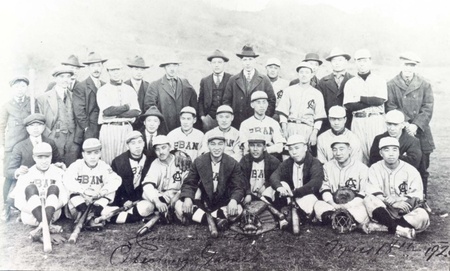

Other community institutions included Japanese Christian churches, Buddhist churches/temples, and prefectural associations. All these organizations helped the Oregon Japanese to adapt to the new environment by satisfying their differing needs. Various cultural and sports groups, such as the haiku and tanka poetry societies, and Japanese baseball leagues, added creative and recreational elelments. Within the close knit community, they also had their own newspaper. Established in 1904, the Oshu Nippo was a prime source of information for both Portland residents and those in outlying areas of Oregon and Idaho. Although the Oregon Japanese were dispersed widely throughout the state, they were well informed of what was going on in their community.12

Notes:

1. Letter from Masuo Yasui to Renichi Fujimoto, April 1, 1907, in Homer Yasui Personal Collection.

2. Many Japanese immigrant males married women in Japan whom they had not known except through the exchange of their photos. Since marriage in Japan only required the transfer of a wife’s name into the husband’s family register, or vice versa, such a practice was perfectly legal.

3. U.S. Bureau of the Census, Fourteenth Census of the United States: 1920; and Fifteenth Census of the United States: 1930 (Washington D.C.,: Government Printing Office, 1922 and 1933).

4. Kazuo Ito, Issei: A History of Japanese Immigrants in North America, p. 499.

5. Ibid., pp. 500-501.

6. Ibid., p. 501.

7. Zaibei Nihonjinkai, Zaibei Nihonjinshi, pp. 1005-1006.

8. Ibid., p. 1005. The farmers associations include the Oregon Cauliflower Growers Association, the Portland Cauliflower Growers Association, the Oregon Pea Growers Association, the Oregon Celery Growers Association, and the Oregon Strawberry Growers Association. Some of these had their own cold storage and packing facilities.

9. Marvin G. Pursinger, “Oregon’s Japanese in World War II, A History of Compulsory Relocation,” p. 64.

10. In Oregon, there were local Japanese associations or equivalents in the communities of Montavilla, Gresham-Troutdale. Columbia Boulevard, Sherwood, Banks, Clackamas, Dee, Hood River, The Dalles, Baker, Independence and Medford.

11. Zaibei Nihonjinkai, Zaibei Nihonjinshi, pp. 1002-1003.

12. Ikkai Kashiwamura, Hokubei Tosa Taikan, p. 231; and Zaibei Nihonjinkai, Zaibei Nihonjinshu, p. 1003.

* This article was originally published in In This Great Land of Freedom: The Japanese Pioneers of Oregon (1993).

© 1993 Japanese American National Museum