David Mura, a poet of third-generation Japanese-American birth in 1952, has always wondered about who he is. He has never considered himself 100% American.

His paternal grandfather came to America to avoid being drafted during the Russo-Japanese War. His father, a second-generation American, grew up as an American and was put in an internment camp during the war, but was successful in American society after the war. In the process, he changed his name from Katsuji Uemura to Tom Mura, partly to become a full American.

David Mura grew up in a Jewish town in Illinois and moved to Minneapolis after graduating from college. Since childhood, he has had almost no connection with Japanese people and has rejected any connection with Japan. However, as a poet, he has often portrayed "Japan" in his works, including internment camps and atomic bomb victims, and somewhere in his heart, he has always imagined going to Japan.

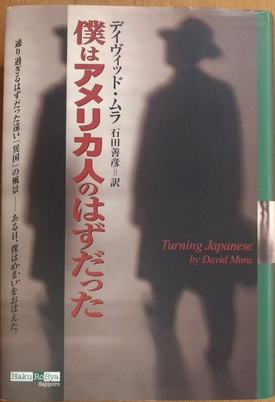

He first visited Japan in 1984 under the US-Japan Writers Exchange Program, and lived in Tokyo for a year with his white wife in the book I Was Supposed to Be an American (translated by Ishida Yoshihiko, Hakurosha, 2003). The original title was Turning Japanese, published in 1993, and it is said to be used at universities in the US in classes on themes such as "coexistence of different cultures" and "Asian Americans."

A record of an inner journey to know myself

Although it is called a travelogue, it is not written from an objective perspective of a different culture. Living in Japan, interacting with various Japanese people, and coming into contact with Japanese society and culture awakened the Japaneseness within himself, while at the same time confirming his identity as an American. It is also a record of an inner journey in which he continues to search once again for who he is and what he is looking for.

He says this immediately after setting foot in Japan from America, a society of diverse skin colors, hair colors, and races.

"When I left the terminal at Narita Airport, I was tired, but excited. At the same time, I was overcome with anxiety. I was surprised to see that all the people at customs looked similar to me."

The two rented an apartment near Mejiro Station in Tokyo and started living there. Everything they saw was new and unusual, and their life was a world of adventure. They also had keen observational skills about people and towns, and when it came to Japanese fashion, they were amazed, saying, "There's no real luxury like in New York, but there are more fashionable people in Tokyo."

The descriptions are also interesting: "On sunny days, futons were hung out to dry all over the streets, looking like confused drunks hanging from balconies."

He can't speak Japanese very well. But he gradually becomes aware of the Japanese in himself and begins to value it. In the city, his foreign friends ignore the traffic lights and cross the road, but he can't do that. His wife Susie asks him to kiss her on the street, but he can't do that like he can in America.

"Being white, Susie attracted a lot of attention and was able to ask others for help when she was in trouble, but I was too embarrassed to do it. I thought that I should be able to make intuitive decisions based on the blood flowing through my body."

As part of his study abroad program, he first goes to meet Shumon Miura, then Commissioner of the Agency for Cultural Affairs, but is told that he should not visit Hiroshima and Nagasaki. He is stunned, as this is something he had hoped to do in advance. However, as someone who has written poems about the victims of the atomic bomb, he ends up visiting Hiroshima.

As he begins to become aware of his potential Japanese sensibilities, his interest in racial issues and the issues of the socially weak and the strong that Japan has had in its relations with Asia, as well as in America, grows. He also develops friendships with Japanese people involved in these activities, and on one occasion visits the local protests against the construction of Narita Airport.

He studies modern dance and Noh, travels to the countryside, and is always eager to absorb new things. He associates with a wide variety of people, including artists, scholars, businessmen, and left-wing activists, and they drink and discuss things at bars. He also visits Enchi Fumiko, who is hospitalized, and attempts to interview her.

One night, while he was at the 7-Eleven near his apartment, he suddenly realized how lonely he would feel if he left this country, and how much he was enjoying living in this country that is like his mother's womb, in a world where people have the same face as me.

In this way, Kokoro enters Japan and begins to see things more deeply, but his attitude worries his white wife. She feels like she has been left out of the Japanese world in which he is deeply involved, and she worries that they will not be able to return to America. In this sense, she is experiencing a sense of alienation as a minority.

A Japanese parent and child facing each other in Japan

During his stay in Japan, his parents, who had never been interested in exploring their own cultural background, decided to visit Japan. There was a conflict between him and his father, who had lived as a second-generation American and established his social status, due to their different values.

He talks about what it was like, but it seemed to him that his parents were refusing to talk about their past, which frustrated him. But when he saw them for the first time in a purely Japanese environment, they seemed different to him. He may have sensed that there was a reason for their way of life.

He recalled that when he was in Japan, he felt like he was at home, something he hadn't felt in America. What does it mean to feel like you're at home, even though it's the first time you've seen and lived there? As long as it's your hometown, there must be a sense of nostalgia and comfort.

As a Japanese person who has lived in this country for a long time, you may not think about what it is that makes you feel at home. That is why, as a Japanese person, I am happy to accept that someone with only a limited connection to Japan felt this way when he saw Japan.

(Titles omitted)

© 2017 Ryusuke Kawai