During the 2016 presidential campaign, Donald Trump said he was open to the idea of Muslims in the United States registering in a database, and candidate Ted Cruz called for law enforcement to conduct surveillance of Muslim neighborhoods. Although these ideas drew outrage by many, President Trump has signed executive orders that effectively banned travel into the U.S. by people from certain predominantly Muslim countries. And multiple Trump supporters have openly suggested the need to segregate Muslims into prison camps, even pointing to the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II as precedent for such actions to “protect America.”

This year marks the 75th Anniversary of the beginning of the World War II mass incarceration of West Coast Japanese Americans. Since few of today’s policy makers have personal experience with these events, some may be tempted to rely on this “precedent” to try to justify various actions against Muslims or others suspected of being terrorists. Conversely, others may become too complacent in thinking that the registration or widespread incarceration of Muslims could never happen in the United States today.

I feel that those Japanese Americans like me who have some personal connection to the World War II incarceration experience should speak out to provide a “living history” of these events. By putting names, faces and stories to the narrative, we can help force politicians to understand that their words and conduct are not theoretical but impact real lives. And by explaining the circumstances once used to justify this incarceration, we can point out the current parallels and warn others to take a stand against any similar encroachment of civil liberties.

“All-American” Lives

My family’s history in America began in 1907 when my grandfather Kunitomo Mayeda emigrated from Japan. He was only 16 years old but had aspirations to study English and become a diplomat to promote better relations between Japan and the United States. As is so often the case for new immigrants, such dreams were never realized. Instead, Kunitomo became a house boy and a cook, and was once employed as a chef at the world-famous Hotel del Coronado. He then got into farming and eventually leased virgin land (Japanese immigrants were not permitted to own land) in the Otai area of San Diego to plant celery and tomatoes. He tilled the fields, installed irrigation ditches, created roads, and built a house. But then the Great Depression hit and he lost nearly everything.

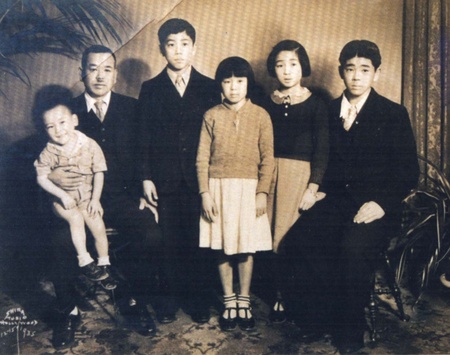

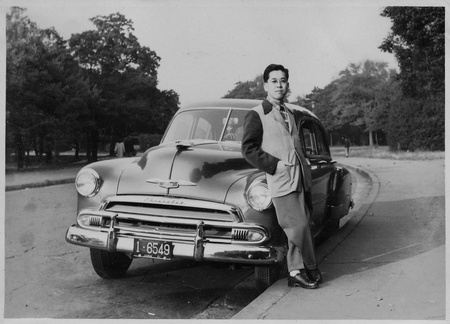

In the meantime, five kids were born including my father Ray, born in 1922 in San Diego. But in the mid-1930s, Ray’s mother passed away. Kunitomo was unable to work and also raise five kids, so the family (except for eldest son Al) moved back to Japan. Kunitomo remarried but eventually returned to San Diego in 1937 and began working as a gardener. Kunitomo’s second wife remained in Japan to raise the children. A few years later, Ray also re-joined his father and brother Al, and enrolled in school. At Coronado High School, there were only about 10 Japanese American students out of about 400 in the student body. But my uncle Al was a star running back on the football team and a “big man on campus.” My father Ray was student body treasurer, on the staff of the school newspaper, and ran hurdles on the track team.

It was basically an All-American existence. But then, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and everything crumbled around the Mayeda family.

“Home Alone”

About three months after the Pearl Harbor attack, my father, an American teenager, was left “home alone.” His sisters Yoko and Moriko, and a younger brother Frank, were still living with their stepmother in Japan. His older brother Al had enlisted in the U.S. Army within weeks of Pearl Harbor. So it was just my father Ray and his father Kunitomo, living in the Coronado Island area of San Diego in the uncertain days on the West Coast after the Pearl Harbor attack.

My grandfather Kunitomo was a leader in the local Japanese Association, a group that tried to help newly arrived immigrants and to maintain cultural ties among the Japanese Americans in San Diego. Within a few weeks after Pearl Harbor, however, the FBI came to question Kunitomo and ransacked the house. “Ray,” my grandfather one day warned my father, “there may come a day when you get home from school and I won’t be here.” Kunitomo was a gardener in his 50s, hardly a rabble-rouser or other threat to America. But he knew he looked like the enemy and, unlike his sons, was an Issei, a Japanese immigrant who was forbidden by law from becoming a U.S. citizen. Kunitomo had the foresight to realize that he might be picked up for further questioning or held by the government, so he prepared my father.

“I have money, American dollars, and I’m going to sew it inside the linings of coats that are hanging in the closet. If I’m not here, rip open the seams and you can live off that money until I come home or you can get a job. You can also seek help from our neighbor,” a kind Mexican American family who was responsible for my father’s love of Mexican food.

Sure enough, one day in March 1942, Ray came home from high school to find the house empty, his father Kunitomo nowhere to be found. Then, within three weeks, Ray himself was forced to leave San Diego and join 120,000 other Americans of Japanese ancestry on the West Coast, to eventually live in so-called “relocation camps” in compliance with Executive Order 9066 signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. In reality, these were American-style concentration camps imprisoning both citizens (American-born “Nisei,” second generation like my father) and aliens (foreign-born, first generation “Issei” like my grandfather) without due process for nearly the duration of World War II.

A fortuitous discovery

I know my father Ray was initially taken from San Diego to a temporary facility on the grounds of the Santa Anita racehorse tracks. He told me of living in a converted horse stable that reeked of manure while the larger camps were being built inland. Eventually, Ray was shipped off to live in one of the three Poston, Arizona camps. Since he had no family with him, he had to live in a barracks with a bunch of middle-aged bachelors. I never learned from my father where his father was taken after he was arrested in San Diego—other than that Kunitomo ultimately ended up imprisoned in a Department of Justice prison camp in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Beyond that, I don’t recall my father telling me any more about what happened to my grandfather. Since my father passed away in 2014, I now can’t ask him. But I did recently learn more about my grandfather Kunitomo through a series of fortuitous coincidences. In April, I was visiting the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles for an exhibit on Executive Order 9066, which set in motion the incarceration of Japanese Americans. As I was about to leave the building, I saw that there was a temporary exhibit about something called the Tuna Canyon Detention Station, about which I knew nothing. Tuna Canyon was located in the Tujunga area of Los Angeles. It was a temporary facility used in World War II to house mostly Japanese immigrants but also some Italian and German immigrants who the government believed were immediate threats to public safety. These included “community leaders” such as Japanese language teachers, Buddhist priests, businessmen, and others. These individuals, along with tens of thousands of others throughout the U.S., were part of a government roundup of alleged risks to national security that began just after Pearl Harbor and largely preceded the incarceration of all West Coast Japanese. As I read the exhibit boards and watched oral histories, it suddenly dawned on me that perhaps my grandfather had been detained at Tuna Canyon. At the end of the exhibit, there was an “Honor Roll” listing the names of each detainee who was held at Tuna Canyon in violation of their constitutional rights. Sure enough, I saw the name “Mayeda, Kunitomo.” So, I surmised, after Kunitomo was arrested in San Diego, he was sent to Tuna Canyon before being transferred to Santa Fe.

* * * * *

Editor’s note: Discover Nikkei is an archive of stories representing different communities, voices, and perspectives. This article presents the opinions of the author and does not necessarily reflect the views of Discover Nikkei and the Japanese American National Museum. Discover Nikkei publishes these stories as a way to share different perspectives expressed within the community.

*This article was originally published on the Huffington Post on September 13, 2017 and modified for Discover Nikkei.

© 2017 Daniel Mayeda