Japan and Temples in Seattle

Seattle, which has a long history of Japanese immigration, once had a Japanese town, and it had almost all the features of a Japanese community. In his "America Story," Kafu Nagai, who came to the United States in 1903 (Meiji 36), was surprised to find that the city of Seattle, his first port of call, was not at all different from Japanese cities.

Among these were religions brought from Japan (such as Buddhism), and Japanese-style temples were built. In Seattle, immigrants were initially influenced by Christianity, but in 1901 the Seattle Buddhist Church (Jodo Shinshu Nishi Honganji sect) was established.

According to the 100-Year History of Japanese Americans in the United States (1961), in 1940, just before the Pacific War, there were four Buddhist churches in Seattle, as well as several Christian churches, Nichiren sect churches, Tenrikyo churches, and other churches.

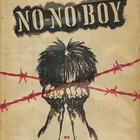

The ninth chapter of "No No Boy" begins with the funeral of the protagonist Ichiro's mother. The funeral of the mother who committed suicide is held at a Buddhist temple, which is modeled after the Seattle Buddhist Temple, a Jodo Shinshu temple locally.

Author John Okada describes the funeral scene in great detail. Perhaps because he is a second-generation Japanese who has witnessed the funerals of his parents, the first-generation Japanese, he does not use Japanese words exactly as they are described, but he does recreate the atmosphere as precisely as possible.

The depiction of relatives, friends, and acquaintances gathering around the bereaved family before the funeral begins, with women taking care of them and men wearing their best attire, drinking and talking, is reminiscent of an old Japanese funeral. Okada said that after writing this novel, he was planning to write a novel about the Issei, so we can imagine that he was interested in the lives of the Issei.

How will Ichiro and his father respond?

During the funeral, the story of his mother's life is revealed.

Her mother is said to have been "born into a farming family in 1898, grew up healthy, went to school, was recognized for her excellent grades, and became a fine young woman who became a teacher. She then resigned from that job to marry a bright, ambitious young man from the same village, and moved across the ocean to America, where a better life awaited her."

My father was a bright and ambitious young man, but after the war, my mother, who had been mentally ill, passed away, and I felt more relief than sadness. He felt a sense of satisfaction knowing that he had arranged for a beautiful coffin and a beautiful funeral.

The following is a description of his father's behavior during the funeral:

"---My father had listened intently to every meaningless compliment. Now, completely satisfied with his own existence, he sat up straight and smiled happily at everyone in the crowd."

He regained his confidence, knowing that he could finally fulfill his role as head of the family by taking the lead role at the funeral. He was finally able to send the supplies to Japan, which he had been unable to do out of consideration for his wife. However, the author subtly hints at the unspoken regret that he should have made that decision sooner.

On the other hand, Ichiro, who does not understand Japanese customs well, sees the funeral as a kind of show and is disgusted by it. Then, when he happens to see his friend Freddie during the funeral procession, he gets in his friend's car and runs away from the scene.

So I once again think about my mother, this time with sympathy.

"--Mom didn't mean any harm. She'd always been wrong, she'd always been mad, she'd always been heartless and stubborn, but she thought she was doing the right thing. It wasn't her fault that things went wrong. It wasn't her fault that we all suffered in the war, that the Japs were driven off the Pacific coast, that we stirred up such a jumble of hatred that none of us could think or feel properly."

And like his father, Ichiro also feels liberated from constraints by his mother's death.

"My mother is dead. Time has pushed her far away. And time will cover my mistakes. My mother is dead. I am not sad. I feel a little freer than before, and a little hopeful."

Freddie has no choice but to run for pleasure

Ichiro gets in Freddie's car and finds out that Freddie, who is also a "No-No Boy" like Ichiro, is having trouble with a Japanese-American who fought as an American. Freddie is scathing.

"They think they're the masters of this country. Get the hell out of my way."

At the same time, they direct their anger at their parents, who are pure Japanese.

"--They shouldn't have come here. They had no right to come here, and they had no right to give birth to me and make me a citizen of the old country. All they do is say stupid things about Japan. What Japan did and did, damn it! If they saw what I became, they'd be a little remorseful, but they don't. They keep saying the same old things as before."

Hearing these words, Ichiro understands why Freddie, who tries to live each day hedonistically and recklessly, is forced to live the way he does.

"It's like water skiing. As long as you're going at a moderate speed, you skim the surface of the water, but the moment you slow down or stop, you sink into helpless nothingness." Some readers may find the sight of a bird being forced to keep going at it rather pitiful.

A moment of peace

After the funeral, Ichiro returns home after saying goodbye to Freddie. Emi, who learned of her mother's death, comes to visit Ichiro. She tells him that she is divorcing her husband, Ralph, who is stationed in Germany. With Kenji also dead, Emi is immersed in a strong sense of loneliness. She jokingly tells Ichiro, "It would be nice to go dancing like we used to. I was hoping you would come and take me out."

Ichiro then suggests that they go dancing, and takes her out, despite Emi's complaint that it's not a good idea because it's the day of the funeral. As they dance in a large nightclub where no one knows them, the two feel peace and happiness for the only time.

This is another moment in the novel where the reader feels a moment of relief.

(Titles omitted, translation by the author)

© 2016 Ryusuke Kawai