On September 2, 2015, the world woke to the harsh image of 3-year-old Aylan Kurdi’s lifeless body washed onshore in Turkey. As a result, many realized the horror of the civil war in Syria, a conflict that has been ongoing since March 2011.

This newly realized crises became a hotbed of debate, and a boiling point for many Islamophobes around the world. While the civil war began as a political protest, it has become entangled with the war against ISIL, an extremist militant group that has been active since 1999.

The conflict in Syria has turned the area into a war zone, with fire coming from both the government and the opposing groups, making the area a living hell for civilians. As a result, refugees have flooded into Europe looking for refuge, and are now being forced to look towards the U.S. and Canada. The refugee policy was debated during the recent Canadian election, with the newly elected Prime Minister Trudeau promising to resettle 25,000 refugees in Canada by the end of this year.

Despite the horrors faced by Syrian nationals, much of the world is reluctant to accept refugees into their country as a result of the terrorist actions carried out by ISIL, most recently the attacks in Paris and California.

Many governments and citizens falsely attribute these attacks to the country of Syria and its citizens, using them as a tool to stir deeply entrenched fear of Muslim peoples, and draw support for a movement against those in need. While many argue that these views result from current events, Islamaophobia in western society dates back to the attacks of 9/11, an event which sparked a 1,700 percent increase in hate crimes against Muslims that year. Using acts of terror as political fuel is far from uncommon, and many parallels can be drawn between the current treatment of refugees and the Japanese internment.

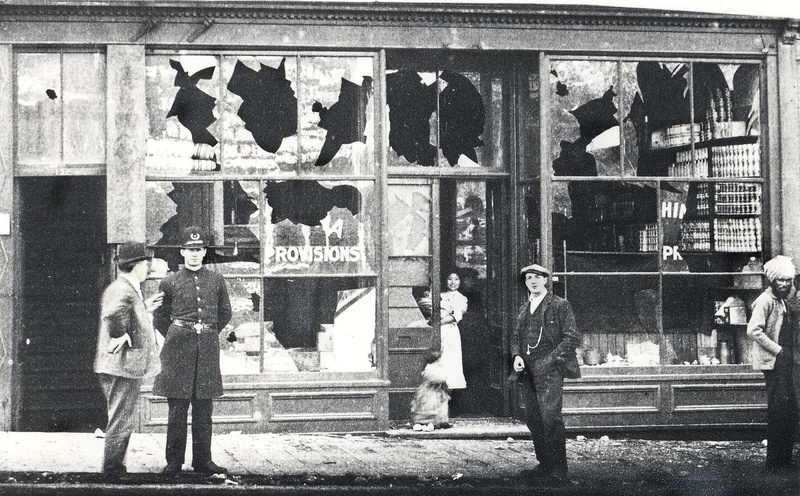

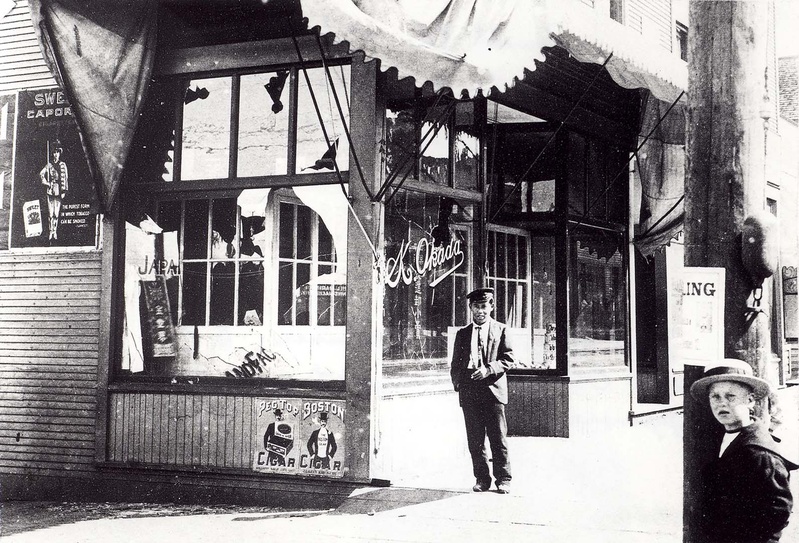

During the Second World War all people of Japanese descent were forcibly interned after the attacks on Pearl Harbor. Animosity towards Japanese immigrants dates back as far as the Fraser Canyon Gold Rush of 1858 which drew a great number of Asian immigrants to Canada in search of wealth. The rush of immigrants put tension on the job market, and the immigrants were blamed for a lack of jobs available to Caucasians.

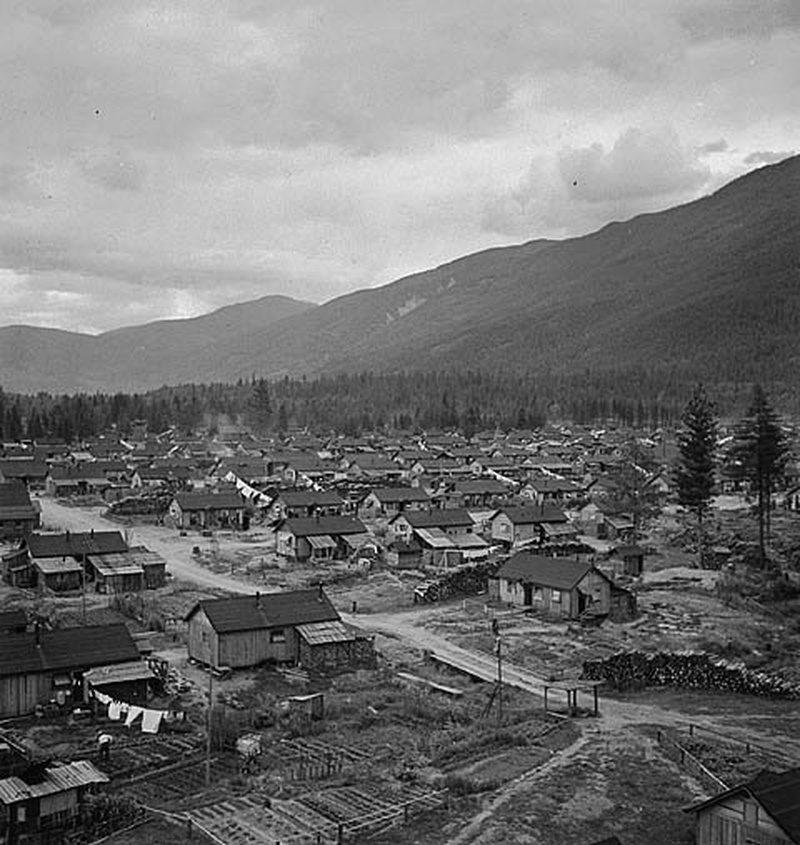

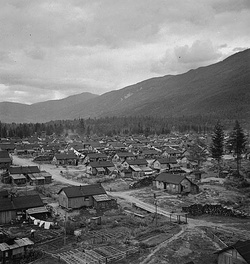

The attack on Pearl Harbor gave reason to invoke the War Measures Act and all Japanese immigrants and Canadian citizens of Japanese descent were removed from their homes, and interned, and not allowed to move west of the Rockies until 1949.

Since the attacks on Paris, presidential hopeful Donald Trump has suggested that Muslims be “compelled” to register in databases, and the mayor of a Virginia town requested that all refugee assistance within the town be stopped using the Japanese internment as justification. The effects of the Japanese internment are not widely known and because of this, the evidence of the financial, emotional, and physical damage caused by this event are downplayed and often forgotten. Few people have come to understand this experience better than lawyer and producer Chris Hope.

Growing up, Hope had what could be described as a typical relationship with his grandmother, Nancy Okura.

In a recent interview, Hope fondly referred to his grandmother as “nurturing, and my co-conspirator for everything.” Mrs. Okura never mentioned her experiences during the War, but Hope always knew that there was a dark experience in her past. As Hope grew older and entered high school, he first encountered the Japanese internment in what he recalls was no longer than a two-page section in the textbook. The account was clinical and cold, it told nothing of the cruel nature of the internment.

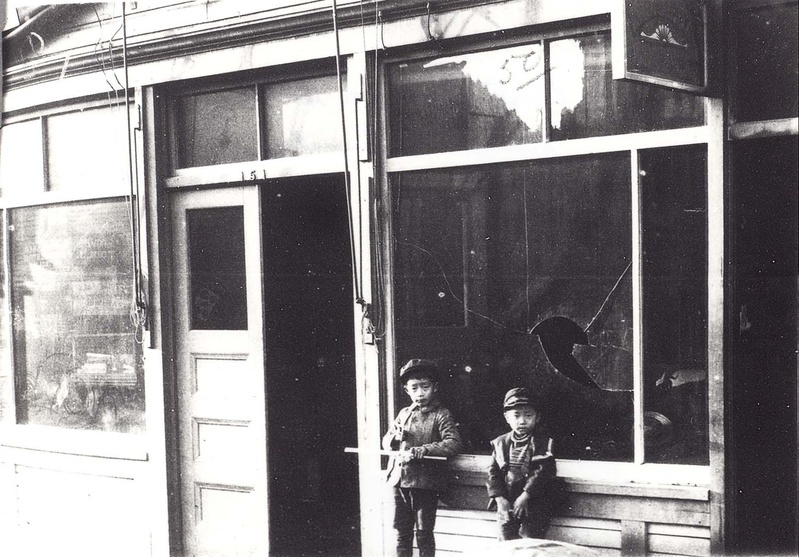

This prompted Hope to look into his family’s history during the internment, and he soon discovered that his grandfather had brought a camera with him when he was interned. “Photos of a well put together family with a car turned into photos of a beet farm in the middle of the winter, harvesting beets by hand,” recounted Hope. The explanation Hope was first given by his grandmother echoed his high school textbook, that the internment just happened, but everything was ok.

Hope made it his mission to find out the true story behind his grandmother’s time in the camps, and in the ’90s he began a self-funded film project called Hatsumi that would take over a decade to complete. During this process Hope began to understand the Japanese philosophy of “shikata ga nai” which means “It can’t be helped”. Hope confessed to thinking that “(…)when I was a brash teenager, I thought it was the most ridiculous thing I had ever heard of.”

“Shikata ga nai” does not acknowledge adversity, and is the reason why the experience of being interned is not often revisited by the Japanese that lived through it. As a result, Hatsumi is one of the few accurate, non-fictional retellings of what happened in the camps because it provides a rare insight into a largely forgotten time in Canadian history.

The lessons that can be learned from Hatsumi are more relevant than ever in these trying times. Looking back on the internment it was obvious that these people never posed a threat to the security of Canada. Throughout their entire internment they endured their property being taken and sold off, inhumane living conditions, forced to work in road camps, and much more. Despite this, they continued with their lives, and went on to reestablish themselves and help to rebuild the society that betrayed them.

Many Muslim critics question why the Muslim community has not condemned the actions of ISIL, and the reason is simple. Much like the Canadians who were punished for the actions of the Japanese, the Muslim community is not to blame for the actions of extremists. Canadians must learn that the actions of the past were ineffective, inhumane, and ultimately illegal.

If there is one thing that can be taken away from the story of the Japanese internment it should be the philosophy of “shikata ga nai”. Canada needs to learn that transgressions should be resolved today, as an acknowledgment and tribute to the many Canadians that endure discrimination in our society in silence.

As a Gosei learning about the internment, I feel a duty to ensure that the mistakes of the internment era are never repeated.

* This article was originally published in the Nikkei Voice.

© 2016 Samantha Sugiyama