Readers here may already be familiar with the fascinating story of Yama and Nagaya, a Japanese sawmill village settlement on Bainbridge Island, Washington. From 1883 to the 1920s, Japanese pioneers created a village complete with houses, churches and temples, a grocery store, laundries, a hotel, and even a photo studio. The village closed when the sawmill closed, and until recently the site has been left largely undisturbed.

Floyd Aranyosi is a faculty member at Olympic College in Bremerton, and is currently the lead investigator for the Yama Project: an archaeological study of this “lost” Japanese village that began in 2014 and has continued into 2016. He was kind enough to speak with me and give me more insight into his work with the Yama Project.

* * * * *

Tamiko Nimura (TN): Can you remember the first time you heard about the Yama Project, or the first time you saw the site? How did that feel?

Floyd Aranyosi (FA): The first time I heard about the site was in 2013. This was before the Yama Project existed. We had just learned that the Bainbridge Island Historical Museum had contacted the Bainbridge Island Metropolitan Park and Recreation District to develop a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) concerning research at the site.

Over the course of the following two years, Dr. Caroline Hartse, Dr. Bob Drolet, and I built the foundation for the Yama Project and developed a curriculum for the Archaeology Field School at Olympic College. Once that curriculum was approved by the college, we sent proposals to the Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation, which is the state level agency responsible for authorizing archaeological research. With their authorization, we then listed the project with the Register of Professional Archaeologists, to get the field school certified.

In summer of 2014, Dr. Drolet and I, along with Ms. Etsuko Evans, began conducting archival and historical research at the Bainbridge Island Historical Museum, assisted by curator Rick Chandler and Executive Director Hank Helm.

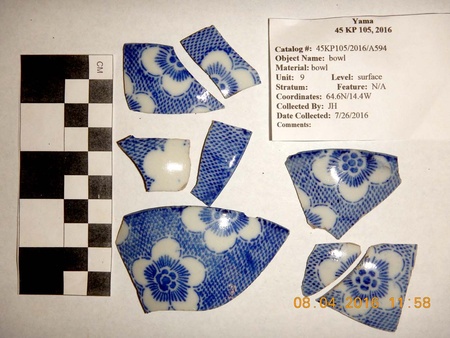

When I first had the opportunity to visit the site, I was amazed. The area surrounding Blakely Harbor has been built up with homes over the past several decades, but the location of Yama has remained almost entirely untouched. Traces of the village could be seen only in the small fragments of pottery and other debris left behind when people moved away. The level of preservation at the site was simply outstanding. This was impressive, particularly since most of the other first generation Japanese settlements in the Pacific Northwest have been destroyed by subsequent construction, so Yama gives us a unique opportunity to learn about the lives of the Issei in the region. I was very excited by that first visit, and I am still very excited every time I go back to the site.

TN: Since I know very little about archaeology’s core principles--how or when is the decision made to excavate objects, versus leaving them where they are?

FA: That’s a great question! There is no “one size fits all” protocol for excavation, since each site is unique. Typically, we begin with what is known as “Phase I” research, in which we investigate the surface of a site by systematic survey, before any digging begins. Often, the distribution of materials on the surface can help reveal activity areas, where people engaged in specific patterns of behavior. For example, the material that is visible on the surface of a garbage pile will be different from the material that is visible on the surface of a cooking area or a play field.

At Yama, the terrain is very steeply sloped, so there has not been much sediment built up since the site was abandoned. The leaves and other materials that decompose into soil are simply washed downhill with each rainy season. As a result, what we see on the surface are artifacts that are heavy enough to resist erosion, or those that have been washed into basins.

This is a significant point, since it means that all of the sub-surface component of Yama is there as a result of deliberate human activity. Anything that is buried below the topsoil was deliberately placed there, whether in garbage pits, outhouses, or other holes dug by the residents of Yama. That means that there is a cultural reason for things being buried, and it is that type of cultural information that interests us.

As a general rule, archaeologists will almost always collect materials, both from the surface and the sub-surface, if they are in danger of being destroyed (e.g. by erosion or construction), but beyond that, we try to focus our excavations in areas where they will reveal the most information about people’s lives. Our goal is to learn as much as we can about the people of the past, while doing as little damage to the site as is possible. It is a difficult trade off. Excavation always removes materials from their context of deposition, so it is inevitably a destructive process. Just like art historians who try to determine the record of ownership of a work of art, or police officers who maintain a record of the chain of custody of evidence, archaeologists try to preserve information about the “provenience” of artifacts. When we do remove artifacts from their place of deposition, we take detailed notes, measurements, and photographs in order to preserve that information.

TN: In your project report, you describe the Yama project report as a little different than traditional archaeology (that is, it’s multidisciplinary)—can you talk a bit more about how you see the project’s approach as different than traditional archaeology?

FA: The multidisciplinary nature of the Yama Project is the part of which I am most proud. We are fortunate at Yama that there are also historical records, written accounts, personal memoirs, newspaper reports, and even photographs of the site during the period of occupation. This historical and archival material provides us with the opportunity to see a much more complete picture of what life was like for the people of Yama. Most archaeological sites do not have this type of information available.

So in addition to doing archaeological field work and lab analysis, participants in the Yama Project are also combing through the archives in local museums. In addition, our partners in the Bainbridge Island Japanese American Community, and our cultural interpreter, Etsuko Evans, have given us insights into Japanese culture and history, which help us to form a more detailed, high resolution interpretation of the site. Archaeology, ethnography, ethno-history, and traditional historical and archival research, along with geology, botany, zoology, cartography, and numerous other disciplines are all important aspects of the project.

TN: What is the most striking thing you have learned since you have been working on the project?

FA: It’s difficult to choose just one! Among the most remarkable things that we realized during the 2016 field season is that the infrastructure of the site was much more elaborate than had previously been realized. This sophisticated infrastructure is particularly evident in the site’s water distribution system. Bainbridge Island historian Andrew Price had described residents drawing buckets of water from a community cistern or well, and we have discovered the location of that cistern. But as we investigated further, it became clear that the cistern was not large enough to have provided all of the water for all of the residents of the site. Tani Creek, which runs through the site, and from which the cistern was filled, is dry throughout the summer.

This discovery inspired us to look for other sources of water for drinking, cooking, bathing, and cleaning. What we found is that there was a system of buried pipes that almost certainly were part of a water distribution network, which may have been tapping rain catchment ponds, possibly including the mill’s fire suppression ponds. By the time Yama was at its peak population, the water distribution network was far more elaborate than historians had realized.

TN: How have the Olympic College students responded to their project work and in their project work? How much do they seem to know about Japanese American history, especially in the Puget Sound?

FA: The students are having a great experience, in addition to receiving valuable, marketable job skills. On the first day of each field season, few students know much about Japanese American history in the Puget Sound, but that knowledge gap is filled very rapidly. By the end of the eight-week field season, students are expected to produce an independent research paper and public presentation, and I have found their research to be very informative.

The students are actually learning about aspects of the Japanese American experience in the late 19th and early 20th century that were previously unknown to historians. Details of culture, such as beverage preferences, food customs, the relative abundance of rice, soup, and pickle dishes used (with all that suggests about diet), and even preferences for specific types of shellfish and avoidance of other edible species are revealed in student research. These are the types of details that people usually don’t bother to record in their memoirs, and that don’t get written about in history books, but they are the aspects of daily life that would have been most familiar to the residents of Yama – so familiar that they didn’t even feel the need to mention them, so the information has been lost for a century.

TN: Do you know if there are plans to make the site visitor-friendly?

FA: One of my hopes is that eventually, the Bainbridge Island Metropolitan Park and Recreation District will develop an interpretive trail through the site, with signs indicating the former location of the buildings and the historical and cultural significance of the site. Currently, there are no formal plans to do so, but that could change if the public requests it.

TN: Have efforts been made to track down the descendants of the Yama residents?

FA: We have had some success in finding a few of the descendants of Yama residents, and we are continuing our efforts to contact more. It is difficult, since descendants have moved all throughout the United States, and of course many people chose not to return to Bainbridge Island after the internment period. Our hope is that descendants may remember their grandparents’ stories of life in Yama, and we can incorporate those stories into our research. So far, we have not been too successful in that goal, but we are optimistic that our efforts will be successful.

TN: I’d love to know more about the project’s connections with/outreach to the Island’s current JA community.

FA: The BIJAC [Bainbridge Island Japanese American Community] is one of our “partner institutions,” and they are supportive of the project. So far, I have had very little contact with the organization, but I am hoping that schedules will allow us the opportunity to present our findings to them and share their stories. Our cultural liaison, Ms. Etsuko Evans, and the project coordinator, Dr. Caroline Hartse, have established contacts with the BIJAC.

TN: What has been one of the most meaningful things about working on the project for you, personally?

FA: I think the most moving, most meaningful aspect of the project, for me personally, is the opportunity to share my excitement about rediscovering this “lost chapter” of history, and teaching students the techniques, methods, and theories that archaeologists use to allow us to “give a voice to the voiceless” people of the past. An archaeological site is a place that was once “home” to people, and all of those personal stories about daily life are lost to us unless archaeologists recover them.

In the movie “Blade Runner,” Rutger Hauer’s character says that all of the moments of his life will be “lost in time, like tears in the rain.” The job of archaeologists is to try to find and preserve the “tears” of people from the “rain” of time. I want to tell the stories of the people of the past who were not able to tell them for themselves. I want to share their lives with the people of the present. Ultimately, that’s what archaeology is all about. We give a voice to the voiceless.

When I am on site, I sometimes feel as though [the unofficial mayor of Yama] Tamegoro Takayoshi is looking over my shoulder, saying “ちゃんとしなさい!” “do it properly!” I feel as though I have a responsibility to him, and to the other residents of Yama and Nagaya to tell their stories. This is my goal at the site - to share the stories that have not been told.

© 2016 Tamiko Nimura