He has just turned 65 and is so young and active that it could be said that this is one of his best times. The newspaper Perú Shimpo celebrated its anniversary on July 1 without any fuss, doing what its staff likes most: serious journalism about Nikkei current affairs, the activities of this community, and the dissemination of the culture and values that are part of it. of your identity; silently facing the modern times of digital communication with very ambitious projects.

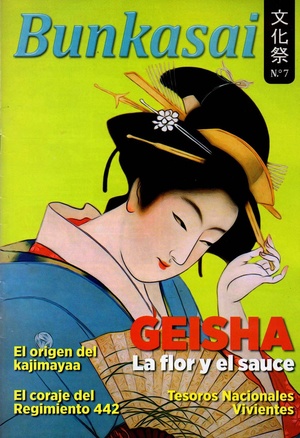

Alberto Kohatsu, managing director of Perú Shimpo, receives us at the offices of this newspaper, a large house in Bellavista, Callao, with the desk full of the day's press, books, documents and preliminary impressions of the newspaper and the magazine Bunkasai, the last initiative that it has had and which is now in its third year and its seventh number. This sui generis publication conducts research on Japanese culture and its history, revealing little-known facets, with exclusive interviews.

Sumo as a tradition and its expansion through countries where there are Japanese immigrants, the genetic and cultural links between Peru and Japan, the figure of the geisha (with an interview with one of them) and the great Japanese masters in various arts and professions, These are some of the topics discussed in the articles of this bilingual publication, printed in full color, which is an unprecedented case in the history of Nikkei journalism on the continent.

“We wanted to thank our subscribers for their support, so we launched this magazine that is delivered free of charge with the Peru Shimpo newspaper using our own printing press,” explains Kohatsu, referring to the Heidelberg Offset machine that takes up an entire room and with the who have been working since the nineties; adding that to achieve the appearance of this magazine and to maintain the newspaper's positive accounts they have had to do budgetary reengineering.

A constant fight

The history of Peru Shimpo is part of the history of Japanese migration to Peru and the Nikkei press 1 . Perhaps one of the factors that most attracts the attention of this bilingual newspaper, which seeks to include English as a third language in future editions, is that it has managed to remain current and in a leadership position, in times of crisis for printed newspapers, especially for those who write in Japanese in the region.

In June 2015, an article published by International Press Digital, called “the largest Spanish-language newspaper in Japan,” warned of the case of La Plata Hochi, a Nikkei newspaper in Argentina that, after 67 years, is at risk of disappearing due to the decrease in its readership, a product of the smaller number of Japanese immigrants and the lack of interest in their descendants; a phenomenon that is repeated in Brazil and Paraguay, where this type of newspapers have economic difficulties.

What has Perú Shimpo done to overcome this economic and cultural crisis in the region? Although there is a strong Nikkei presence in Peru (it is estimated that it is greater than 100 thousand people), it has not been easy since for many years the newspaper reported losses. However, they have managed to maintain a continuous periodicity (it appears every day, except Mondays) which has been essential to meet their readers and renew themselves with products and communication strategies that are having an effect.

The hard beginnings

During World War II, Peru declared war on Japan, all Japanese newspapers were confiscated and the community's leading journalists and businessmen were deported. Martina Hasegawa of Igarashi, granddaughter of Diro Hasegawa, founder of Peru Shimpo, says that when the war ended and her grandfather returned from the Crystal City concentration camp, in the United States, he saw that the Japanese immigrants were still hiding and incommunicado.

For this reason he decided to create the newspaper, so that they would have a means of communication. “I went door to door, in Lima and the provinces, looking for support. He asked the Japanese immigrants to collaborate with something and to convince them he offered them to be shareholders,” recalls Martina, who is currently president of the board of directors of the newspaper founded by her grandfather. That is why the first edition appeared with 116 pages, only one of them in Spanish, the rest in Japanese.

“It was of that size to be able to raise enough money and get a venue that served so that the Issei had a place to meet before the Peruvian Japanese Association was created,” says Martina, who comments that her grandfather spoke to many people to learn. how a newspaper should be made and what machinery was needed. The three-story premises of Jr. Puno, in the center of Lima, had an auditorium on the last floor where all the community celebrations took place.

For 40 years, until 1990, the news boxes were assembled with 'katsuji', molds with which the kanji were printed one by one, and for which the diagrammer had to read them backwards. “Until Mr. Ryoichi Jinnai sent a donation for the printer that continues to operate until now,” adds Martina. Since the first Nikkei newspaper appeared in Peru, at the beginning of the 20th century, only two of them continue to circulate: Perú Shimpo and Prensa Nikkei (founded in 1985).

Journalists with commitment

Various journalists have passed through this newspaper, among them Chihito Saito, who signed his current affairs column with the pseudonym 'Don Jueves'; Luis Tsutomu Ito (creator of the “Green Book”) together with Ricardo Isamu Goya (who, at more than 80 years old, continues as a staff editor); Alfredo Kato (specialized in entertainment journalism) and Alejandro Sakuda; the latter as directors of the newspaper. But one of the most remembered and loved was Ricardo Mitsuya Higa.

He wrote a column under the pseudonym 'Three Arrows', in which he made analyzes and human reflections that have not lost their validity; But he became internationally known when he dedicated himself to bullfighting, to the point of traveling to Spain to make a living from bullfighting. Upon his return to Peru, he worked at Perú Shimpo, where he began valuable research to translate from Japanese the so-called “Green Book”, about the beginnings of Japanese immigration, which had been published at Perú Shimpo.

Efforts like this are part of the mystique of a newspaper that has always maintained a commitment to truth and ethics to touch on issues such as Alberto Fujimori's candidacy in 1989 (which he addressed objectively) to the kidnapping of the Japanese ambassador's residence in 1996. “During the kidnapping, many versions were made but we did not publish anything until we were sure that the information was correct,” says Martina Hasegawa, whose husband was held hostage.

New challenges

Many changes have occurred since the newspaper was written mainly in Japanese and had only two spreads to today, in which 16 pages are printed (24 on Fridays and Sundays), several color pages are included and the format was changed to tabloid size , in 2010. Perú Shimpo has been in constant renewal and that is due to the spirit of continuing to offer an attractive means of communication for the Nikkei community.

“Most of our pages are now in Spanish because in Peru we are already between the fifth and sixth generation,” explains Alberto Kohatsu. More than the loss of the language, what the managing director is most concerned about are the Nikkei values and identity, which can be transmitted thanks to publications such as Perú Shimpo and reach new generations through digital technology. Only on website 2 they have had more than a million visits, not counting social networks, with more than three thousand followers.

But their efforts do not end here. The board's plans aim, unlike the rest of the Nikkei newspapers on the continent, to expand. “We are training editors-translators thinking about creating a news agency from Peru to Japan, China and Korea. We also want to create a media and marketing section for small and medium-sized businesses,” says Kohatsu, who does not believe that Japanese-language newspapers in Latin America have to disappear.

“It's a matter of them seeing Nikkei culture as a 'niche marketing',” he explains, and knowing that their role is to promote the values of an Eastern culture that, in the midst of an individualistic society , seeks “a natural formation, in harmony with nature,” adding that this is important so that Latin American Nikkei appreciate it more and pay more attention to it.

Grades:

1. “ The Japanese press in Peru ” By Alejandro Sakuda (September 20, 2010)

© 2015 Javier Garcia Wong-Kit