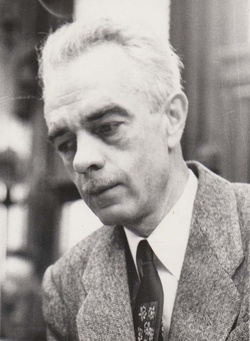

The inscription on the front page of Michi Nishiura Weglyn’s landmark book, Years of Infamy: The Untold Story of America’s Concentration Camps, reads: “Dedicated to Wayne M. Collins Who Did More to Correct a Democracy’s Mistake Than Any Other One Person.” At a time when people barely knew Colllins’ name, Nisei historian Weglyn called attention to the attorney responsible for almost singlehandedly fighting deportation and restoring citizenship to more than 5,000 Americans of Japanese ancestry who had renounced their U.S. citizenship. The tedious and time-consuming process that involved researching and filing some 10,000 individual affidavits from both renunciants and witnesses consumed Collins’ life for no less than two decades.

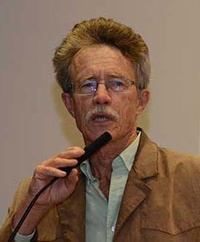

Speaking at the Tule Lake Pilgrimage on July 6, 2014, his attorney son Wayne Collins Jr., detailed his father’s behemoth struggle to ensure no persons of Japanese ancestry were denied U.S. citizenship after the tumultuous days of WWII. It had been 70 years since his San Francisco-based father made the first of several visits to the Tule Lake camp as one of the only outside lawyers to investigate what was going on in the stockades. Collins’ address also coincided with his father’s death almost exactly 40 years to the day on July 16, 1974.

I was fortunate to be at the biennial event ten years earlier in 2004 when the younger Collins had accepted an award on his father’s behalf from those who owed their very presence there to the man responsible for giving them back their citizenship. Collins’ son was responsible for taking on some cases his father left unfinished, including the defense of Iva Toguri who had been falsely accused of being a Japanese spy. As tears of joy and cheers of gratitude filled the auditorium, the younger Collins graciously accepted the award.

I remember thinking what a toll the relentless and selfless work that his father undertook must have taken on a young boy’s life. Yet he calmly spoke of his father’s around-the-clock work schedule and volatile temper as if they were necessary demons of a man fighting for something as important as democracy.

This year, addressing a crowd consisting now of mostly descendants of the renunciants, the 60-something attorney began to display some of his father’s anger. After all, it was only natural for the heir to his father’s advocacy throne to inherit some of his rage, not to mention his brilliance. Pointing his finger directly at those who failed the renunciants, the otherwise mild-mannered lawyer began his address with accusations directed at two time-honored institutions, the national American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL). According to Collins, cavorting with the Roosevelt Administration to rob citizens of their rights, the national ACLU and JACL were culprits whose self-interest far outweighed their concern for democracy’s promise of freedom for all.

Leading up to the war with Japan, the national ACLU, preeminently regarded as the guardian of civil liberties, aligned itself with the leadership of the New Deal. Determined to stay in the good graces of the Roosevelt administration, ACLU head Roger Baldwin was thus close to those leaders responsible for the very creation of the camps. This symbiotic relationship resulted in the ACLU’s refusal to investigate any reports of abuse—in spite of widespread rumors of prisoners being held in stockades and brutally beaten by the War Relocation Authority police. The ACLU also initially refused to take any of the incarceration test cases.

Jumping in to fill the void was a small chapter of the ACLU in Northern California run by his father’s friend and ally Ernest Besig. “My father was a very difficult man,” said Collins. “You should meet Ernie Besig.” On a humorous aside, Collins went on to say that [legal historian] Peter Irons said Besig called his father a terrier. Collins injected, “My father would be insulted. He thought of himself as a wolfhound.” In any case, they were “quite a pair.”

Besig was hearing reports, even from non-Japanese camp workers, of horrible things like “findings of black hair and blood on the walls and floors” of the stockades. However, Besig was ultimately forbidden by the national ACLU to intervene on behalf of the stockade prisoners or even to visit the Tule Lake camp without prior written approval from Baldwin. His hands tied, Besig turned to Collins, an independent non-ACLU attorney, to take charge.

Multiple visits to the camp by Collins resulted in the telltale photographs of prisoners being dragged to the stockade and first-hand reports by wives being denied access to their imprisoned husbands. In fact, stockade prisoners were not only kept from their wives and families, they were denied lawyers or any kind of hearing. It was not until Collins threatened legal action (over the objections of ACLU’s Roger Baldwin) that the stockade was permanently shut down, more than a year after Collins’ first visit.

The younger Collins then told the mostly Japanese American audience at the pilgrimage that perhaps even more damning during this bewildering time was the position taken by the JACL, an organization that theoretically existed to protect the interests of Japanese Americans. In looking back, he said, he was “struck by the make-up of the JACL founders—all professionals, doctors, accountants, attorneys” who had a “potential stake in social climbing.”

Just as the ACLU sought to be on the side of the President, the JACL courted relationships to gain access to power. As Collins described it, “ The JACL was not willing, not emotionally able to protect Japanese Americans because it was contrary to their personal limited own interests.”

Collins was particularly struck by the JACL’s interference in Heart Mountain, when JACL representatives were sent to convince members of the Fair Play Committee to withdraw their objection to appearing for pre-induction physicals. Thus, in legal matters associated with the draft resistance, the JACL took an early stand against it. (Note: A.L. Wirin, who served as counsel for the JACL, eventually ended up representing the Heart Mountain Resisters on his own—not at the behest of the JACL—and Collins acknowledged that “he did a good job.”)

Collins, Jr. then recounted the events that led to his father’s prolonged legal odyssey to recoup American citizenship for those who renounced, a struggle that curiously also indirectly involved the JACL through its legal counsel Wirin, who also served as counsel for the Southern California chapter of the ACLU.

Abo v. Clark, a class action suit filed in Northern California by Collins, was the landmark case that led to the nullification of the renunciation. It was based on his father’s legal argument that renunciation was invalid because the decision to renounce occurred under extreme duress, i.e., behind barbed wire among people subjected to threats of the draft, threats from fellow inmates, fear of family separation, stockade violence, and a myriad of other factors that depicted what the younger Collins referred to as “an insane asylum.”

His father filed affidavits that described people literally going insane under the pressure, notably being terrorized by the Hoshidan, the government-sanctioned Japanese nationalist group of inmates that terrorized others at the Tule Lake camp. Such conditions led to suicides and other brutal acts, most notably a woman hammering her child to death. As Collins’ son emphasized, there was no way that the decision to renounce could by any stretch be considered a rational one.

As a result of Abo v. Clark, the court ruled in 1948 in favor of the renunciants by restoring citizenship to all of them. However, in a strange turn of events, a separate lawsuit filed in Southern California by Wirin (who after the war became law partners with JACL leader Saburo Kido) resulted in the 9th Circuit Court of Appeal’s ruling that an individual hearing was necessary to reverse each claim of those who renounced, thus voiding the Abo ruling, then also on appeal. It was agreed that individual affidavits, rather than separate lawsuits and hearings, could be filed instead, but the burden of proof was to be placed on each renunciant to demonstrate that his renunciation was invalid. As a result, Collins had to file separate affidavits and present a separate case for each and every renunciant. Representing a job of monumental proportions, Collins’ son sighed, “Abo v. Clark became my father’s life.”

In listening to Wayne Collins, Jr.’s profound message, it became clear what motivated his father to sacrifice his entire life and possibly his family to devote himself to making sure that not one renunciant was denied citizenship under his watch. It was as simple a principle as protecting the Constitution against self-interest and government gone awry; it was at the heart of what his father stood for.

Wayne M. Collins recognized that it took individuals without any official connection to government and its institutions to make sure that its leadership was bound to principles found in the Constitution, even if it meant criticizing people in power to achieve those ideals.

His son clearly understood the burden of his father’s calling. He pointed to a typically gruff note left him by his father (“Read page 428.”) found in a copy of Plato’s Apologia of Socrates after his father’s death. The elder attorney referred to a passage in which Socrates said he could never have served all the people of Athens had he accepted any office from the state or any honors from the bureaucracy. Bound by truth, independence, and personal integrity, Wayne M. Collins, like Socrates, fought for everyone’s Constitutional rights. When leadership and institutions threatened to deny the renunciants those freedoms, Collins devoted a lifetime to undoing this wrong. As the humble torch-bearer stood before an audience of grateful beneficiaries, Wayne Collins, Jr. understood better than anyone what this fight meant.

Wayne Collins - Tule Lake Pilgrimage 2014 from Claudia Katayanagi on Vimeo.

© 2014 Sharon Yamato