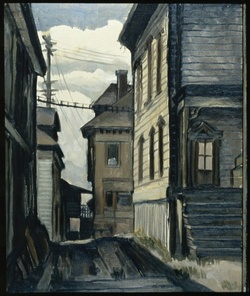

Artist Kamekichi Tokita came to America from Japan in 1919 and achieved moderate success painting familiar scenes near his Seattle home—a back yard, an alley, a street market—in comfortable, muted tones reflecting the damp Northwest weather.

But after years as an artist and sign painter in his adopted home, life for Tokita and his family changed forever with the December 7, 1941, Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

Tokita began writing a diary that day which would last throughout the war: “My heart is full to bursting. In the space of a moment, our lives became worthless in this society,” he wrote. “Not only have we become worthless, we’re unwanted. It would be better if we didn’t exist.”

History and the prejudices of war almost made it so. Tokita and family were sent to Idaho’s Minidoka Relocation Camp in 1942, not to return until the war ended. In frail health after the war, Tokita died in 1948.

Many Northwest artists from the 1930s have been remembered and celebrated for their place in American art. But Tokita and several other Issei, or first-generation Japanese, who were very popular and active at the time—such as Kenjiro Nomura (Tokita’s sign-painting business partner) and Takuichi Fujii—have been largely forgotten by history.

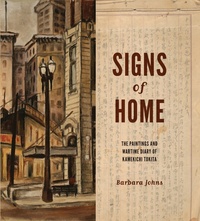

Signs of Home: The Paintings and Wartime Diary of Kamekichi Tokita, a new book from the University of Washington Press, seeks to change that, and to restore Tokita, at least, to his rightful place in art history. The book is both a biography of Tokita written by curator, author and art historian Barbara Johns, and the complete text of the artist’s extraordinary wartime diary.

Johns, who is pursuing a doctorate in art history at the UW, also has curated Painting Seattle: Kamekichi Tokita and Kenjiro Nomura, an exhibit opening Oct. 22 at the Seattle Asian Art Museum at Seattle’s Volunteer Park.

“This is a reclamation, I think, and an important one,” Johns said, discussing the book and its creation. “Because these artists were very well known, at least regionally, in the ’30s. They were part of a circle of progressive artists—there was an organization, a collective, they called themselves the Group of Twelve. And what I propose in the book is that they were forgotten. Their works of art were taken off the walls, they were gone.”

Johns said Tokita and Namura did know and correspond with famous Northwest artist Kenneth Callahan, who often championed their work. “There definitely was a strong relationship there—Callahan wrote frequently about their work. It was he who really praised it and continually called them out,” she said.

But when Callahan articulated what came to be called the Northwest School in 1946, Johns said, “He credits the white artists with looking to Asia for inspiration—but there’s no mention of this generation of very fine artists of the ’30s—interpreters, intermediaries who knew that culture.”

The spark for Signs of Home came when Tokita’s family was finally able, decades after the war, to get all three volumes of the diary translated and compiled together. UW Press Executive Director Pat Soden remembered that Tokita’s eldest son, Shox, brought the diary to him with the idea of publishing it for family and other Japanese-Americans who experienced wartime internment.

“I suspected that the diary had broader significance than just as a family keepsake and that it should be published to reach a larger audience,” Soden said. “However, to be truly ‘published’ it would need a scholar to provide context and interpretation.” He mentioned it in passing to Johns, a former curator at the Seattle and Tacoma art museums who had briefly researched Tokita when writing the life of artist Paul Horiuchi. Johns was immediately interested.

“From that serendipitous conversation came the book we are now celebrating. It’s a wonderful story, and I am very proud to have it published at the end of my tenure as director of the Press. It is certainly among my top 10,” Soden said. He called the story of its creation “a wonderful example of why this business can be such a pleasure.”

Signs of Home is a biography and a diary, but it is also a format for displaying the splendid art of Kamekichi Tokita. “There is a kind of intimacy…the kind of view you get when you walk past somebody’s yard every day, or their storefront,” Johns said. “You gather a deep familiarity with the little things.”

Johns wrote in Signs of Home, “In the hands of an artist, the paintings transform the specifics of site to an enduring expression of time and place.”

With this volume finished, Johns said she wants to look further into this marginalization of Japanese Issei artists of the 1930s “and why they were excluded from the legacy. Whether it was intentional—a habit of wartime—or a product of the “exceedingly close relationships” among the white artists.

“Nevertheless, there’s no credit given,” she said. “And credit is due.”

*This article was originally published in UW today on October 19, 2011.

© 2011 Peter Kelley / University of Washington News and Information