How appropriate that on the 75th Anniversary of Miné Okubo’s pioneering graphic memoir, Citizen 13660, hailed for its groundbreaking account of the WWII incarceration by a Nisei held in camp, the Japanese American National Museum would present an exhibition drawn from its own impressive collection of Okubo masterworks. When the Museum was developing its reputation as the repository for notable Japanese American art more than twenty years ago, its innovative senior curator and art mastermind, Karin Higa, convinced Okubo and her estate to donate the massive body of work that includes more than 200 original sketches from the now-classic book, as well as an early manuscript complete with handwritten notes. Higa, who died in 2013 at the young age of 46, is forever recognized for her passionate melding of history and art, and she doubtless saw in Okubo, who died in 2001, a prime example of that indispensable merging.

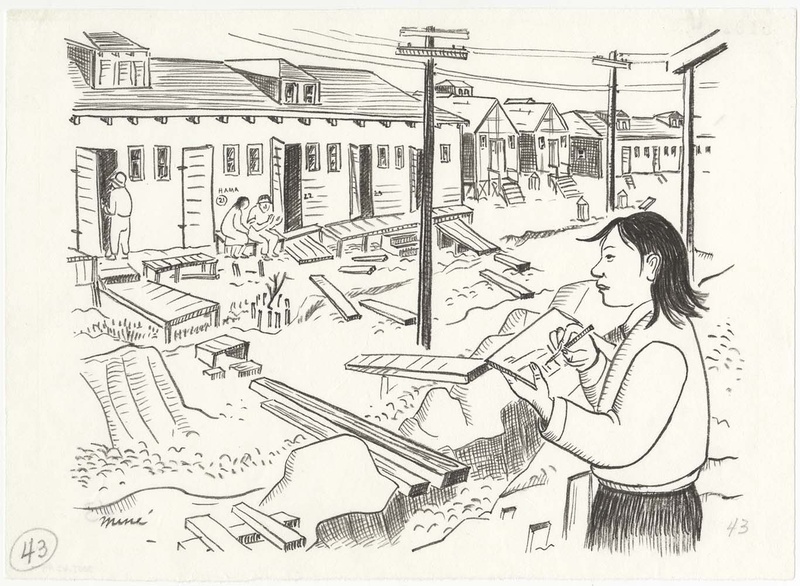

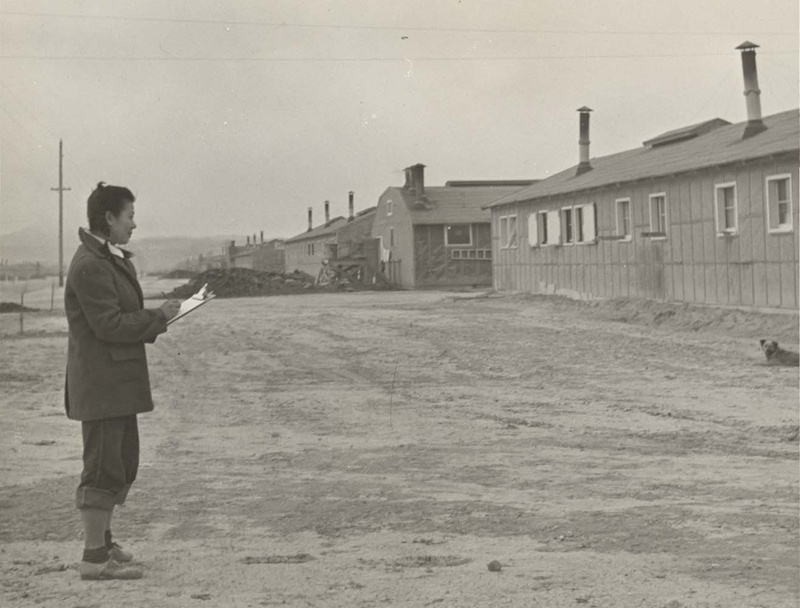

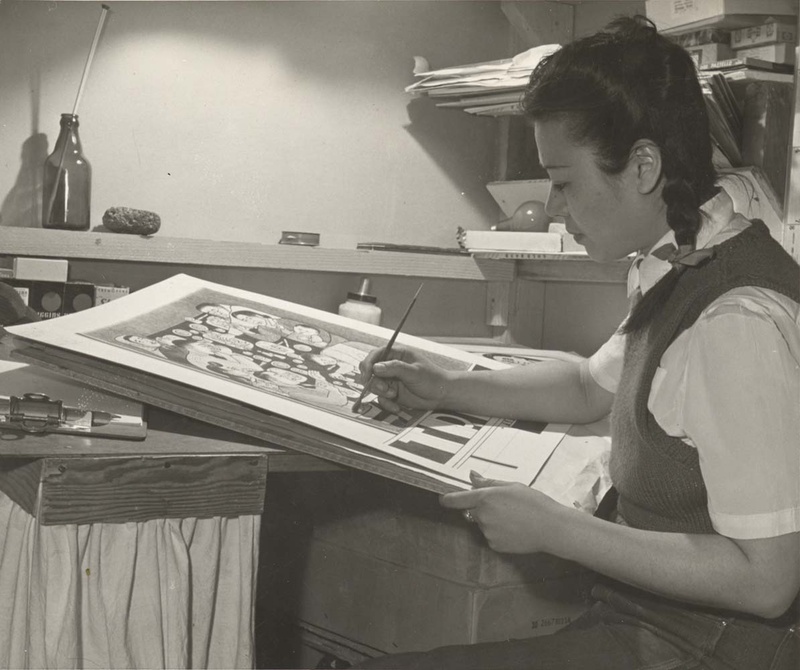

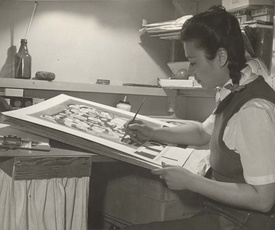

With fierce determination and a workaholic mindset, Okubo captured daily scenes through thousands of sketches that depicted her stay at the Tanforan assembly center in December 1942 to her imprisonment at the Topaz camp until 1944. For the exhibition, titled Miné Okubo’s Masterpiece, The Art of Citizen 13660, curator Kristen Hayashi, who holds a Ph.D. in history from the University of California at Riverside, would unquestionably agree that the historical value of Okubo’s art cannot be underestimated. In Citizen 13660, she notes the details in the artist’s illustrations that show an insider’s view crucial to an understanding of the mass detention. Among the sketches that caught Hayashi’s attention was a map of Topaz (featured in the camp literary review, Trek) that was drawn by Okubo with such vivid descriptive details like “mosquitoes” and “sewer smell.” Hayashi comments that there were also hundreds of less detailed sketches with short descriptions, such as “men watching grass grow,” or “flowers in jelly jar”—a total of a staggering 1,500 to 2,000 sketches created in a nine-month period. The sheer volume of work is a tribute to Okubo’s work ethic and an amazing contribution to the historical record little documented on paper.

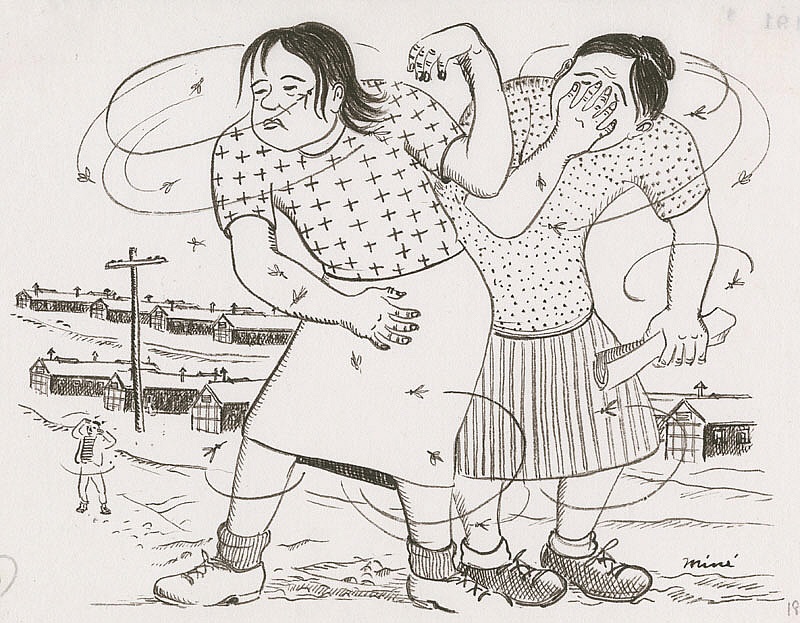

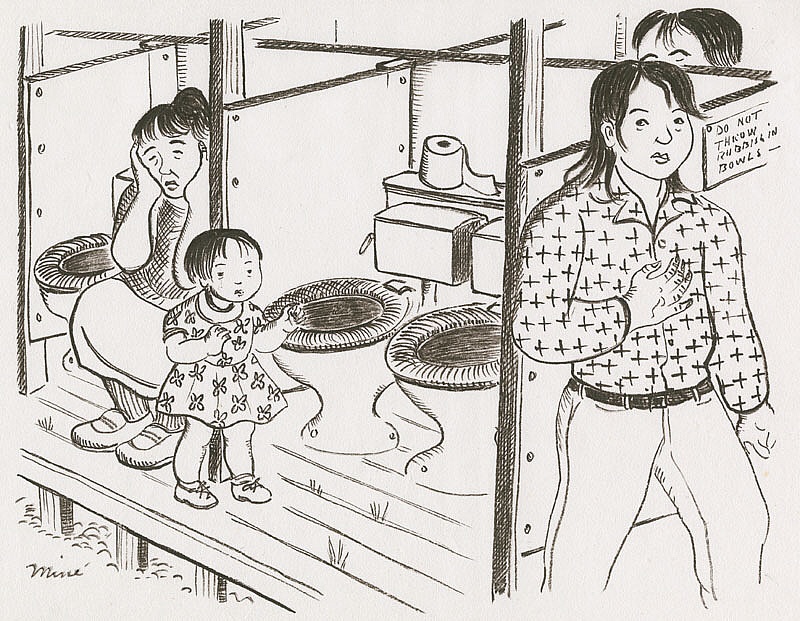

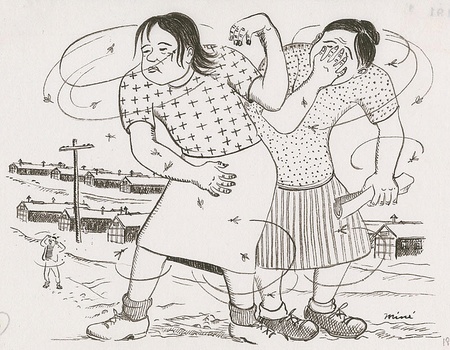

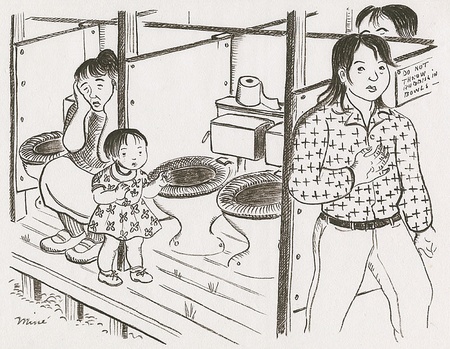

Because some of the more hostile parts of camp life were off limits for War Relocation Authority photographers and cameras initially banned for detainees, it was Okubo’s goal to be both camera and record keeper. Whether depicting children peering at the flush toilets tightly arranged in twos, nude older women climbing into pails and dishpans to bathe, or men and women holding their noses to the stench of poor sewage, Okubo caught camp life in all its unpleasantness.

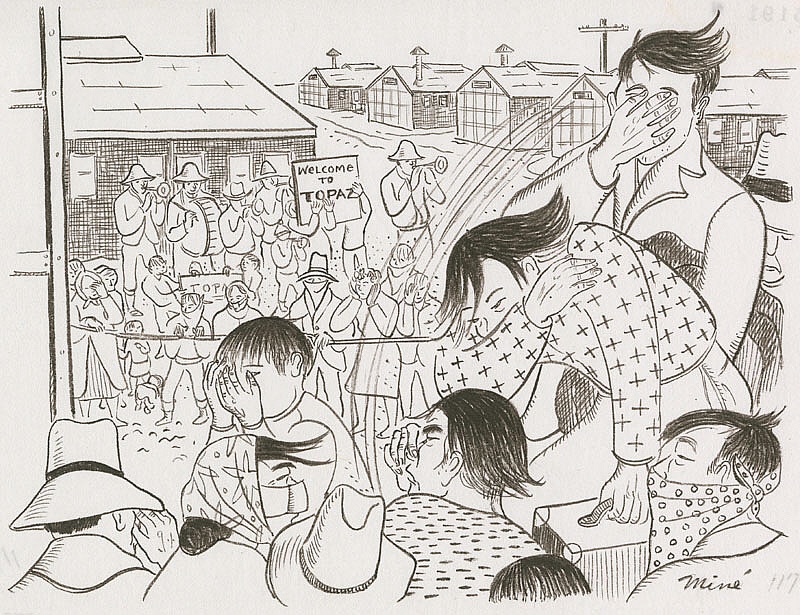

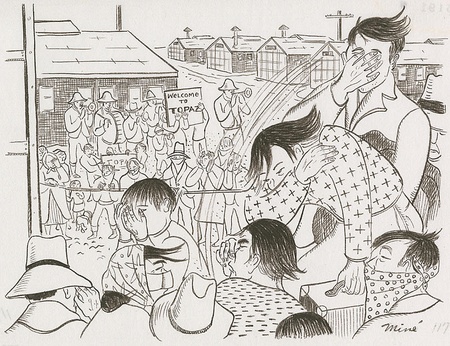

Her drawings are accompanied by rich explanations replete with both humor and irony. Hayashi cites one of her favorite drawings that shows Okubo and her brother, who were separated from their father, mother, and siblings, when they first arrived at Topaz. The newly arrived were greeted with a Boy Scout band playing and people cheering while holding a “Welcome to Topaz” sign. Despite the celebratory welcome seen in the background, Okubo shows incoming arrivals covering their faces in agony, unable to see anything due to the dust. “When we finally battled our way into the safety of the building,” she writes in her caption, “we looked as if we had fallen into a flour barrel.”

According to Hayashi, it was difficult to select only 28 of the more than 200 illustrations from the book for the exhibition that comprises two galleries. Hayashi says she was fortunate to have the help of the summer Getty intern, Rose Keiko Higa, who just happens to be the niece of the gifted woman responsible for securing the collection. Together, they pondered over every drawing and carefully read each caption to present Okubo’s work in a way that would hopefully make both Karin Higa and Miné Okubo proud.

The second gallery highlights what Hayashi considers the goal of the exhibition, i.e., to show the process that led to the creation of Citizen 13660. Fortunately, the JANM collection holds keys to that process, including the quick sketches that led to the manuscript draft and ultimately to the final published version. In some cases, according to Hayashi, edits—both Okubo’s own changes and other modifications—altered the meaning of the illustrations and text. Also noteworthy are the different styles captured in various versions that offer insights into Okubo’s thought process as she went from sketch to final drawing, most always showing an increasingly powerful sense of humanity.

Although the scope of Okubo’s work cannot be featured in this exhibition, it is important to note that her work as an artist spanned decades prior to and following the war. Born in Riverside, CA, to a mother who was herself an artist and graduate of the Tokyo Art Institute, Okubo, an art and anthropology graduate of the University of California at Berkeley, was awarded a postgraduate fellowship allowing her to spend a year and a half in Europe just before the war broke out. Upon her return, she became active with the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project as well as with the San Francisco Art Association, ultimately leading to an assistant’s job with famed painter Diego Rivera. While Okubo was still at Topaz, the San Francisco Museum of Art featured her camp drawings in an exhibition in 1943, which in turn led to her work being featured in Fortune magazine. Fortune assisted in relocating Okubo to New York in 1944, where she earned a reputation as a book illustrator until returning to full-time painting in 1960. The diversity of her work can be seen in additional pieces in the Museum’s collection that feature colorful paintings of such diverse objects as cats, fish, and horses.

Still, it is as camp illustrator and documentarian that earned Okubo her renown now 75 years after Citizen 13660 was published. Nearly 50 years after its publication, it was awarded the American Book Award, a true sign of its universal staying power. With its unique sensibility and historic insight, one can only hope that Okubo’s work will continue to live on to enlighten present and future generations about a period in history that many once wanted to forget.

* * * * *

Miné Okubo’s Masterpiece: The Art of Citizen 13660

At the Japanese American National Museum

From August 28, 2021 – February 20, 2022

For the 75th anniversary of artist Miné Okubo’s graphic memoir, Citizen 13660, JANM commemorates the milestone anniversary with a special exhibition with her original artwork from their collection.

© 2021 Sharon Yamato