Interviews

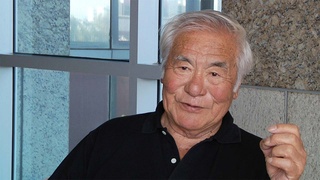

His testimony has more credibility because of his race

Being assigned to military intelligence gave me some credentials later on to say I was in military intelligence. There’s a certain mystique about that—actual or assumed—[which] nevertheless works in one’s favor.

And the other opportunity, besides meeting Aiko, was to meet other Nisei people with whom we’re still in contact. That helped because then I was able to flush out, to a great extent, the archival kind of material that we were running across. Then, I guess, being able to testify before [Congress], being able to prepare myself to testify with authority, required the knowledge and the skills—most of which were transferred to me from Aiko. With her assistance, I could go before the congressional committees and say with authority, with back-up material, with resources, what I was able to say.

Because I was not Japanese American, there was no doubt about my testimony. But if somebody else [a Nikkei] had said the same thing, if Seiichi Watanabe had [made a similar statement] under the same circumstances, with the same background as mine, it wouldn’t have carried the weight that I was able to present. [My testimony was acceptable] just because of my face [being a Caucasian].

Date: August 26, 1998

Location: Virginia, US

Interviewer: Darcie Iki, Mitchell Maki

Contributed by: Watase Media Arts Center, Japanese American National Museum