Previously, I wrote an article for Discover Nikkei on how the incarceration of Japanese Americans affected the 1942 election and how Japanese Americans managed to participate in the election. Despite the traumatic events of being sent to camp and efforts by racist politicians to keep Japanese American from voting, many Japanese Americans still participated in the election through absentee ballot. For some Nisei, the election represented the last defense of their citizenship rights against government deprivation. For others, the site of barbed wire on Election Day was a sobering reminder that their civil liberties had been reduced to almost nothing.

Eighty years ago, the 1944 election, which made history as the first wartime presidential election since 1864, gave rise to its own dilemmas for Japanese Americans. First, Nisei voters faced the question of whether or not to support President Franklin Roosevelt in his run for a historic fourth term.

Although Roosevelt had notoriously signed the executive order that incarcerated them, many Japanese Americans supported Roosevelt because he made few public statements on Japanese Americans—most of which were positives—backed the War Relocation Authority’s resettlement policy, and supported the creation of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team.

In contrast, at both the national and state level, Republicans and several Democrats attacked the War Relocation Authority as a New Deal-type bureaucracy that “coddled” Japanese Americans and was “too soft” on dealing with pro-Japan cliques. Even more so than in 1942, politicians—mostly anti-Roosevelt candidates—invoked the image of returning Japanese Americans as a fear-mongering tactic. Several Republican candidates declared that they would either support a permanent ban on Japanese Americans returning to the West Coast or even their deportation from the country.

Among the presidential candidates, the question of Japanese American resettlement received little attention during the 1944 presidential campaign. Republican standard-bearer Thomas Dewey of New York made no direct comments on Japanese Americans. However, he chose as his running Governor John Bricker of Ohio, who gave a speech in April 1944 in which he declared that West Coast residents should have the right to determine whether or not to allow Japanese Americans to live in their communities. Secretary of Interior Harold Ickes rapped Bricker for his hateful remarks, arguing that he did so to “further his presidential aspirations” and in the process had “deliberately kicked the Constitution in the teeth.”

Roosevelt, for his part, made no remarks about Japanese Americans during the campaign. Privately, he was concerned about whether Japanese Americans would become a political football during the election.

As Greg Robinson notes in By Order of the President, Roosevelt first tried to get his advisers to secure the backing of California Governor Earl Warren for West Coast resettlement, then held off any attempts to end the exclusion of Japanese Americans from the West Coast until the November election. When he finally agreed to let Secretary of War Henry Stimson announce the end of exclusion on December 17, 1944, it was because he knew the Supreme Court was about to issue their ruling in Ex Parte Endo declaring mass exclusion of concededly loyal citizens illegal.

Candidates for Congress, however, were less bashful in bringing up Japanese American resettlement among voters in order to score political points. In the California senate race, Republican Candidate Frederick Houser (then Lieutenant Governor of the state) declared that, should Japanese Americans return to the state, it would result in blood and violence.

At the kickoff of his campaign on September 1, Houser told a group of voters in Santa Rosa that he was not in favor of allowing Japanese Americans to return to California and declared that politicians in the other parts of the country needed to be “made familiar” with California’s Japanese issues. Houser went after his opponent, incumbent Democratic Senator Sheridan Downey, for not addressing the “needs” of Californians. On October 13, during a speech in Riverside, Houser asserted that, once re-elected, Roosevelt and the Democrats would “release” Japanese Americans to the West Coast. Even more damning, Houser charged that Roosevelt, Ickes, and other Democrats had wanted to allow Japanese Americans to return to California in July, but hesitated because “they remembered there would be an election on November 7.”

Republican Senator Hiram Johnson—one of the leaders of California’s anti-Japanese movement since the early 20th century—broke with the tradition of neutrality among colleagues, and endorsed Houser over his fellow senator Downey. (Johnson was already in failing health, and he died in August 1945). Yet Downey triumphed over Houser, and remained in office until 1950.

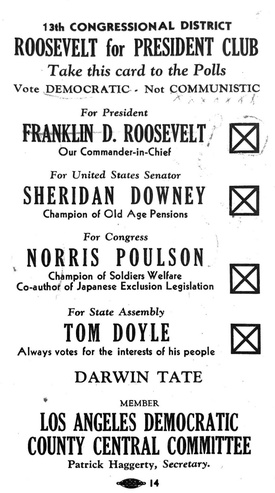

In House races, several West Coast politicians also invoked Japanese American resettlement to attack their opponents. Chief among them was Republican Norris Poulson, representative for California’s 13th District (Pasadena-Eagle Rock). During his time as a member of the California State Assembly, Poulson had co-sponsored legislation with Sam Yorty and Jack Tenney that would keep Japanese fishermen from working in California. According to the press, the goal of the bill was to “disperse the Japanese colony on Terminal Island.”

Once elected to Congress in November 1942, Poulson joined his fellow West Coast congressmen in attacking the War Relocation Authority for being too “liberal” in its treatment of Japanese Americans during their imprisonment. He wrote a monthly column for the Hollywood chapter of the American Legion, where he frequently criticized the government’s release of Japanese Americans from the camps. In November 17, 1943, Poulson accused WRA director Dillon Myer of lying to the House of Representatives during his testimony regarding his handling of Tule Lake (the article appeared a few weeks after the Tule Lake riot on November 4).

In his campaign materials for the 1944 election, Poulson proudly described himself as as “Co-author of Japanese Exclusion Legislation.” Citing his extensive anti-Japanese record, Poulson pleaded for voters to not elect his opponent, Ned Healy, whom he accused of being a communist.

Despite Poulson’s incumbency and red-baiting, Healy won the election. Poulson would regain his seat in the House from Healy two years later, and later served as mayor of Los Angeles. A postscript to Poulson’s story comes from Dillon Myer: when Myer started his career in the Bureau of Indian Affairs in 1950, he ran into Poulson in the House. According to Myer, Poulson told him “Dillon, for some time I have been wanting to tell you that you were right and I was wrong during the war.”

Like Poulson, incumbent Democratic congressman John Costello, who bore the moniker of “Hollywood’s Congressman,” engaged in anti-Japanese race-baiting. In the May 1944 primaries, Costello proudly flaunted his part in authoring Public Law 503, the law which gave Executive Order 9066 teeth by making it a felony for any Japanese American to live inside the West Coast exclusion zone. In a campaign poster labelled “The Enemy,” Costello proudly listed his role in passing the law “which keeps the Japs out of military zones in California” and his role in investigating the camps. Despite his efforts to appeal to his constituents, Costello lost the Democratic primary to Hal Styles, a radio commentator for Warner Brothers.

Ironically, midway through the election, journalists uncovered that Styles was a former member of the Ku Klux Klan in New York state. Although Styles claimed he had disavowed his connections to the KKK in 1930 and publicly criticized the group, his association with the KKK damaged his reputation. At the same time, Styles received the endorsement of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), which Republicans claimed was communist-run.

Costello, for his part, publicly disowned the Democratic Party, which he claimed was communist-controlled, refused to endorse Styles, and cast his lot with Dewey and Bricker. Styles’s opponent, Republican Gordon McDonough, won the election handily.

To be sure, not all anti-Japanese politicians in California lost their elections; Carl Hinshaw, Clair Engle, Jack Z. Anderson, and Alfred James Elliott, all held their seats in the House. Among the few politicians friendly to Japanese Americans who remained in power included the newly-elected Helen Gahagan Douglas, Senate incumbent Sheridan Downey, and Jerry Voorhis.

Douglas, a longtime civil rights activist, was once blacklisted from visiting the Tanforan Assembly Center due to her leftist activities. During her time in Congress, Douglas backed legislation supporting the naturalization of Japanese immigrants.

Downey was perhaps the only incumbent candidate to not speak negatively of Japanese Americans. And while Voorhis hesitantly supported the West Coast delegation’s anti-Japanese policies in 1942, he split and later supported Japanese Americans. He would lose his seat two years later when a new Republican, Richard Nixon, effectively used red-baiting against Voorhis. The Republican strategy of smearing the CIO, developed in 1944, would form a blueprint for Nixon’s successful challenge.

© 2024 Jonathan van Harmelen