Miki had no problem adjusting to Japan due to being only two-years-old when he arrived. In fact, he felt like he had been born in Japan as he had no memories of Canada, and Japanese became his first language.

He got along well with friends and played baseball using a bat made from bamboo. Every morning they got up around 6:00 a.m. so they could play baseball for an hour before school. Miki played third base and was a good batter and home run hitter. He remembers what a great day it was when his dad bought him a baseball glove and a wooden bat which he then shared with his friends. “Life was good. I did very well academically and played baseball as clean-up batter and third baseman. So, I had a wonderful time in Japan.”

Miki has almost no recollection of being seriously discriminated against during his childhood in Japan. The only incident he can remember was having his cap taken by some other kids and being called “Foreigner!” Perhaps due to his young age at the time he did not find this appellation as deeply insulting as the older children did.

However, the situation was very different for Shig, who, in contrast, was nine years old when he arrived in Japan. He recalls having a much more difficult time adjusting. Unlike his younger brother, he had fond memories of Canada and his friends there and how much he had enjoyed life as a small child in the internment camp. Although his parents spoke Japanese at home and he could sort of get by, he had not learned to read or write Japanese before arriving in Japan, so he had to start elementary school in Japan in grade two at the age of nine. He recalls often being called various names including “Foreigner!” and getting into fights with the other kids but adds that he was a tough kid and didn’t lose.

Somehow, despite the frequent fights, he was eventually able to make some good friends. He was also a native English speaker although it seems that even this was not always an asset. For instance, he later told Miki that when they had English speech competitions in school, he would not be allowed to participate because he was considered to have an unfair advantage.

He also remembers often feeling hungry. Compared to what he ate in Canada, the food he could eat in Japan at that time did not taste good, so he always wanted to return to Canada. Years later he told his wife Akemi that this frequent hunger and looking at the delicious bento of a classmate whose parents owned a restaurant gave him a dream to open a restaurant someday so he could make good food, a dream that would one day be fulfilled after his return to Canada.

Shig also recalls most of the young adults (and some teenagers who were just a few years older than him) quickly getting good jobs at the American military bases, which enabled them to do much better economically than the Japanese people around them. He also wanted to go to work and clearly recalls his father telling him he couldn’t as he was too young. So, he had to content himself with helping his father in the field.

Although Miki’s recollections of that period are happier, he does remember some unpleasant experiences that he and all his Japanese classmates had to endure. For example, elementary school kids were required to drink makkuri (a herbal medicine that kills worms in the stomach) at school. The teacher would come with the makkuri during lunch hour and make the kids drink it.

Miki remembers being required to drink this medicine several times. It tasted awful and he couldn’t endure it. “I drank it the first time, but the second time I didn’t. I paid my friend five yen or something to drink it for me. I really hated that stuff!”

The school also used to spray a kind of white powder on the girls’ hair to kill lice. All the boys were required to get a bozu haircut (shaved head) at school from Dr. Kamike, the school doctor. Miki, however, was spared from Dr. Kamike’s haircuts thanks to his mother being the local barber. Miki chuckles:

So, I was the only guy with long hair! I could get my hair cut anytime I wanted. Kamike sensei lived five doors from me and used to get his hair cut by my mother. So, he never cut my hair, but he cut all the other boy students’ hair.

Unlike some of his classmates who ate mugi (grain) or brown rice, Miki was able to eat white rice for his school lunches.

I guess, because we had a rice field, we always had white rice to eat…On especially lucky days I also had a fried Japanese style egg and sometimes salted salmon…and my dad used to grow all the vegetables. That’s why my favorite foods even now are rakkyo, umeboshi, takuwan, and cabbage, all of which can be bought in Vancouver now. I still eat lots of those.

The elementary school in Taga had a field and the students learned how to grow rice and vegetables. The school also kept chickens, rabbits, a goat, and pigeons. Each grade would take turns looking after the various animals. There was a mountain just behind the school, so during the noon hour the kids would go up the mountainside and play. They learned about what plants grow on the mountain and what could or could not be eaten, and they used to pick berries and other things they could eat.

In the postwar years, there was a dearth of sports equipment in the Japanese schools. Most of the equipment they did have was directly donated by parents and other individuals. Also, the kids would go and catch inago (locusts) in the rice fields to raise money for sports equipment. Miki recalls,

Each grade had a project, and each one of us had to catch so many inago and bring them to school and (the teachers) cooked them. I remember the inago getting very red…then they put them on a mat and dried them. Then some food company would come and buy them.

Also, there was a special herb called yakiso that grew by the riverside. Each grade was assigned during the summer holiday to collect a certain amount of it. Then we would bring them to school. I used to go and pick it all the time. The school would sell the herb to a pharmaceutical company…and then we could get a new baseball. Because the students had to raise money like this to buy sports equipment, they appreciated it more. They also had to clean the school and were taught to mend their own school uniforms.

About that time the new phenomenon of television was gradually starting to spread in Japan, and the kids in Taga would go to the local electrical goods shop where the shop owner would let them watch. Miki remembers this shop being a social gathering spot where all the kids would watch TV together.

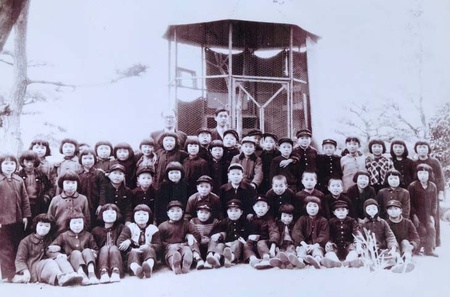

Even now Miki is still in contact with many of his childhood classmates and friends in Japan. “Most of them are still alive and I meet them at class reunions…Whenever we had a class reunion, about 40 of them would come.” As of now he has online contact with 19 of them. He also used to visit his elementary school teacher every time he went to Japan, but the teacher passed away in 2021.

The next chapter will be about the return of the Hirai family to Canada.

© 2024 Stanley Kirk