Today, he has inspired a pay-it-forward “Rice for All Collective” project to help community elders secure healthy Asian-inspired meals. The “OG-San,” his social media moniker, is from “ojiisan,” which in Japanese, means uncle or esteemed “old man.”

* * * * *

Tell us about your Japanese grandparents from Japan and your parents growing up in Seattle.

My paternal grandparents, Kiyoichi and Kiyomi Miyahara, immigrated from Hiroshima. They had three children: Hiro (my father), Tak Miyahara, and Leah (Miyahara) Sakamoto. My father and Uncle Tak were born in Olympia, Washington, as my grandparents worked on an oyster farm there. It seems that early Japanese settlers were involved in the local oyster farming business, which is also an important industry in Hiroshima.

My maternal grandparents, Kikujiro and Riki Mano, immigrated from Shizuoka, Tokyo and Chiba. They had three children — Kiyo (my mother), Tosh Mano, and George Mano, all of Seattle. Riki died from tuberculosis when my mother was a child before the family was sent to Minidoka incarceration camp. Later, my grandfather married Tase Takahashi after release from the camp.

My maternal grandfather had a greenhouse in Seattle’s Green Lake area where he grew flowers and vegetables to sell at Pike Place Market. He later built Earlington Greenhouse in the Skyway neighborhood. We lovingly referred to my maternal grandparents as “Greenhouse Jiichan and Baachan.” My Uncle Tosh continued to run the greenhouse until he retired.

You grew up in downtown Seattle. What was that like?

On social media, I call myself “older_than_I_5_OG_san” as I am older than Seattle’s I-5 freeway and we lived right next to it before it was built!

My paternal grandparents left work on the oyster farm to manage hotels and apartments in downtown Seattle. Their first was an old hotel on First Avenue above the old Anchor Tavern. I remember their stories about dealing with corroded bathtubs from the Prohibition Era (1920-1933) when bootleg gin was “produced” in their hotel. Later, they managed the New Latona Hotel on First Avenue across the street from the current Crocodile (First Avenue at Wall).

Until I was in elementary school, we lived in the Manhattan Apartments, across the street from Market House Meats (Howell Street at Minor Avenue) which set a very high standard for my taste in corned beef! This is where the current Metropolitan Park buildings are located next to the freeway. We were right next to the Smith Gandy Ford dealership, a busy commercial area. I learned how to ride a bicycle in their parking lot.

As my young neighborhood friends started moving away, we moved to the Summit Arms apartment, on Summit between Pike and Pine Streets, around 1956. Shortly after, the neighborhood was dug up and the freeway started going in… all through Seattle.

I learned later that there was strong Japanese-community business support and financing assistance for the Japanese who owned hotels. A lot of my friends lived in, owned or managed apartments, such as the Fujii, Okamoto, Tanaka, Tanabe and Harada families.

When we lived downtown, I loved shopping with my mom at Pike Place Market and visiting her stepmother’s relatives, Seiji (Curly) and Pete Hanada. They had a vegetable stand in the corner by the current “Rachel the Pig,” across from Pike Market Fish; Seiji is pictured on a plaque next to the elevator on Western Avenue. His daughter, Diana Kuzaro (Hanada) married Donnie Kuzaro of Don and Joe’s Meats, also in the market.

Most shopping days also included visits to Mutual Fish, then on 12th Avenue, or Uwajimaya in the International District (ID, its earlier name). On lucky days, we’d have lunch at the now-closed Tenkatsu restaurant (South Main at Sixth Avenue South).

Tell us how you became the first Director of the International District Health Clinic in 1973 and launched your career in health services?

When my family moved to the Beacon Hill neighborhood, I went to Franklin High School. I played in the first Franklin Jazz Band and later, some of us started the “Nine Lives” band, which became quite popular locally and across the state.

A fun side note: After I left Nine Lives, I sold my trombone to Terry Takeuchi, of today’s Terry’s Kitchen restaurant, so we have a long history together!

I started at the University of Washington (UW) studying pre-medicine. After I cruised through pre-med, I studied architecture, biology and botany. I took first-year medical school classes through the Equal Opportunity Program (EOP, which has helped under-represented ethnic minority, economically disadvantaged and first-generation college students at UW). But none of that stuck.

While I continued to play in Nine Lives, I also continued to have an interest in the medical and health field. I began volunteering at the Asian Community Health Clinic, a free weekly evening clinic on Beacon Hill. There, I worked alongside Janyce Ko Fisher, who today has a gallery named in her honor at International Community Health Services (ICHS) in Shoreline, Washington.

The mission of the original clinic was to provide bilingual services to overcome income, insurance coverage, cultural and language barriers. Some readers might remember Dr. Eugene Ko’s Jefferson Park Medical Clinic (near today’s Beacon Hill light-rail station). He donated the use of his clinic for a group of Asian physicians and nurses to provide free medical services.

During that time, I was also volunteering in the ID, a neighborhood steeped in historic racism, which was being challenged by large development projects. By then, the incarceration of Japanese Americans had already decimated a good portion of Japantown and I-5 had cut the neighborhood in half. Huge infrastructure projects such as a multi-modal transportation terminal and Kingdome Stadium threatened the neighborhood’s survival.

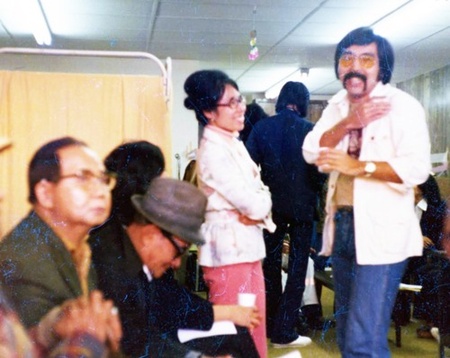

At the time, there was a large group of activists that united to help on every community project no matter who owned it, which in my view, was unique. One of the most memorable food-related projects was helping terrace the Danny Woo Community Garden. It hosted the first community pig roast with the legendary “Uncle Bob” Santos. As with most ID program start-ups during the 1970s, a beer with Uncle Bob in the Four Seas Restaurant bar (present location of Uncle Bob’s Place) turned into a plan.

The plan for the Asian Community Health Clinic was to transition its volunteer efforts to a more permanent organization, so funding was sought to expand the efforts. We started out with funding from King County Council Member Ruby Chow, Community Development Block Grants through the City of Seattle, state funding, and a Nursing Research Grant assisted by Sister Heidi Parreno, who later joined the staff.

The original clinic was built at a gambling hall that Uncle Bob helped secure next to the old Kokusai Theater (Maynard Avenue South; present location of Northwest Asian Weekly). Architect Joey Ing designed the clinic on the back of a cocktail napkin. Later, the construction was led by Kaz Ishimitsu (of Ishimitsu & Sons, building contractors).

I became the first Executive Director at the International District Community Health Center, which later became International Community Health Services (ICHS). From my experience as the first director, I found my health systems interests were in policy and management. Accordingly, I entered the UW Masters of Health Administration and Planning program. After graduate school, I began work at the Seattle/King County Department of Public Health as its jail health administrator.

Later, I became the Regional Health Services Division Manager, which managed the communicable disease programs and epidemiology, including building King County’s HIV/AIDS program. From that position, I became the Chief Administrative Officer of the Health Department and then became Washington State Secretary of Health under Governor Mike Lowry. The first month after I became Secretary, we had the Jack-In-The-Box Escherichia coli outbreak – the ultimate intersection of public health activities with the restaurant industry.

*This article was originally published in The North American Post on July 20, 2023.

© 2023 Elaine Ikoma Ko / The North American Post