The first Japanese immigrants to New York were quite different from their West Coast counterparts. Initially, the majority of Issei (first generation Japanese in America) came to New York, not to make quick money and return to Japan, but to engage in U.S.-Japan trade and learn Western ways. Many of these New York Issei came from Tokyo and other large cities, rather than from farming prefectures.

Japanese Entrepreneurs

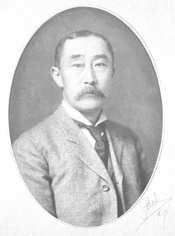

Rioichiro Arai, New York, September 1899. Gift of Haru Reischauer, Japanese American National Museum (98.84.31)

The first Japanese in New York were ambitious young businessmen. In 1875, Momotaro Sato, who had studied at Boston Polytechnic Institute, returned to Japan to spread the word about opportunities in the U.S.-Japan trade. In 1876, five young men—Rioichiro Arai, Toyo Morimura, Rinzo Masuda, Chushichi Date, and Toichi Suzuki—left for the United States with Sato. They became known as the “Oceanic Group”—named for the steamship on which they traveled—and were pioneers in promoting U.S.-Japan trade. Their early days were a struggle. In Arai’s words:

We came to America, determined to succeed at any cost. Upon setting foot in New York, we endeavored to live thriftily and save money. We stayed at a dirty boardinghouse operated by an Irish American on the 900 block of Third Street. We ate only bread and tea in the morning and a few cookies at lunch. In the evening, we went to a cheap restaurant and had the cheapest food there. Those days, I thought American beef was so tough, but now I realize it was because I had the cheapest meat. Every morning, I walked from the boardinghouse all the way to my office on Front Avenue.1

The Oceanic Group before their voyage to the United States. Left to right: Rioichiro Arai, Toichi Suzuki, Momotaro Sato, Toyo Morimura, Rinzo Masuda, and Chushichi Date. Tokyo, March 1876. Gift of Haru Reischauer, Japanese American National Museum (98.84.22)

Eventually Arai formed his own company and became the largest importer of Japanese silk to the United States. Morimura promoted the import of ceramic goods from Japan, and by 1905 owned a Japanese ceramic factory and was importing high-quality goods.

Arai felt it was important to live in the United States while overseeing his business. Rather than settle down in New York, which in Arai’s opinion was no place to bring up children, he had a house built in Connecticut at the New York borderline. The pine trees in the area reminded him of where he grew up in Japan.

New York became the center of trade between Japan and the United States. Many Japanese companies and banks opened branches in New York, and Issei-owned businesses flourished. A few Issei professionals also had great influence in the community. Jokichi Takamine was among the most prominent. Dr. Takamine, who came to New York in 1896, became a well known chemist and entrepreneur, whose entry into the white community helped to improve Japan America relations. Takamine was instrumental in establishing the Japan America Society, the Nippon Club, and a Japanese news bureau.

Arai residence, Riverside, Connecticut. Standing, left to right: Meiroku Morimura, Tazu Arai, Tetsuo Ushiba. Seated, left to right: Toyo Morimura, Banya Hoshino, Tochan Ihaya, Miyo Arai, Yoneo Arai, Kaisahu Morimura. Gift of Haru Reischauer, Japanese American National Museum (98.84.25)

Domestic Workers

By the early 1900s, the population of Japanese in New York had grown to more than 3,000. Approximately two thirds of the Japanese in New York were domestic workers, the majority of whom came from the West Coast. Other laborers came as passengers on ships and freighters. Others, shipboard cooks and servants, came ashore at the Brooklyn Navy Yard and stayed in New York, either because they were let go by their employers or because the “jumped ship.” A small Japanese community grew in Brooklyn, complete with a hotel, boardinghouses, and restaurants.

Domestic work was virtually the only employment available to Japanese laborers in New York. American unions refused to admit them, saying that they were “unfamiliar with the city’s geography, incompetent in the English language, and different in race.”2 Many Japanese laborers, however, fought for their interests, establishing a labor organization of their own and publishing newspapers. Sen Katayama, a renowned Japanese communist who died a working class hero in Moscow in the 1930s, was an early leader, of a group of Issei labor activists which formed a major center of the Japanese labor movement in the United States.

Meanwhile, a handful of domestic workers eventually became successful business people and professionals. Toyohiko Campbell Takami, is an example. He arrived in 1891 as a captain’s boy on a British ship and stayed in a Japanese boardinghouse in Brooklyn. He found a job as a mess-boy on a navy ship and, assisted by his Sunday School teacher who was impressed with his enthusiasm and ambition, was attending high school in Massachusetts by 1893. He went to Cornell University for medical training, opened a clinic in Brooklyn, and eventually became chief of the Department of Dermatology at Cumberland Hospital. Dr. Takami became one of the most prominent Issei leaders in New York.

Probably because of the large number of domestic workers who could not afford to have families, the early Japanese community was overwhelmingly a bachelor society. As late as the 1920s, the number of Japanese women in New York was less than 20 percent of the community.

Community Organizations

The New York Issei community had no geographic center. Unlike the “Japantowns” on the West coast, New York Japanese were spread throughout the city. Domestic workers often lived with their employers and were widely dispersed. The Japanese in New York depended on social institutions for their sense of community.

Although the entire New York Japanese community probably numbered about 3,000, there were two major Japanese American newspapers before World War II. The first East Coast paper, Nyuyoku Shuho, came out in 1897, catering mainly to student laborers in the Brooklyn area, but it soon folded. First published in 1900, the Nichibei Shuho (Japanese American Commercial Weekly), an English-Japanese newspaper, had a steady readership of Japanese businessmen. The newspaper was taken over by Dr. Takami in 1916 and renamed the Nichibei Jiho. Another successful newspaper, the Nyuyoku Shimpo appeared in 1911 and was published twice a week until the outbreak of war.

Community organizations reinforced the class line that divided the early Japanese American community. Businessmen and professionals founded the Japanese Association of New York, the Japanese Credit Union, and the Nippon Club. Alumni and students at New York University and Columbia had their own associations. Japanese laborers and indigent students also had their own, more loosely organized, associations including labor unions. Christian youth groups, providing both social and financial aid, were formed in Brooklyn and New York City.

Dinner given by Dr. Jokichi Takamine for Baron Eiichi Shibusawa at the Lotus Club, New York, December 1, 1915. Gift of Haru Reischauer, Japanese American National Museum (98.84.47)

Prelude to Pearl Harbor

The relationship between Japan and America had a profound effect on the Japanese American community. In 1931, Japan began military aggression in Northern China, stirring up widespread anti-Japanese sentiment in America. The Great Depression made things even worse. In order to improve an American attitude toward Japan and Japanese in the city, the Issei in New York began pro-Japanese propaganda campaigns which sometimes backfired:

Japanese immigrant leadership started to concentrate on the promotion of Japanese American friendship, distributing pamphlets explaining the Sino-Japanese problem and launching fund-raising campaigns to help Japan’s cause… However, the result (of all the propaganda) was not favorable. For example, a Japanese domestic worker attempted to tell his American employer about the Sino-Japanese problem, but ended up having an argument and losing his job. On another case, a Japanese store that catered to whites distributed pro-Japanese pamphlets to its customers, which resulted in a big decrease in sales.3

Japan and the United States were on a collision course. In 1940, Japan joined the military alliance between fascist Italy and Nazi Germany. The United States broke its commercial and navigational treaties with Japan, and began restricting trade. In July, 1941, the U.S. government froze all Japanese assets in the country.

Japanese trading companies in New York realized that their businesses were doomed and closed their offices. Many of the Japanese-born workers and their families returned to Japan. By 1942, the number of Japanese in New York plummeted from some 3,000 to about 1,500. The great majority of those who stayed were bachelor laborers. Only a handful of professionals and merchants remained. There were few Nisei (second generation Japanese Americans) left in New York.

In August, 1941, Issei leaders formed the Committee for Democratic Treatment for Japanese Residents in Eastern States, desperately trying to convince the American public that they were not responsible for Japanese aggression in Asia and that they loved America. The organization’s “Statement for the American People” read:

We reaffirm our loyalty to the United States government and our service to the American democracy on behalf of all the Japanese residents in eastern states. We all are law-abiding and peace-loving people. And our children are American citizens. If American naturalization laws allow us, we, though born in Japan, would become American citizens right away…All we care now is how to render our service and show our loyalty to our adopted country…We earnestly hope that we will maintain friendship with American people and live peacefully together.4

Although prominent white politicians and religious and social leaders assured the remaining New York Issei that America’s democracy would not tolerate any sort of discrimination, over the next few months it became clear that theirs were empty promises.

Notes:

1.Mizutani, Shiozo, Nyuyoku Nihonjin Hattenshi (New York: Nyuyoku Hihonjinkai, 1921), p. 355.

2. Ibid., p. 379.

3. Hokubei Shimpo, ed., Nyuyoku Binran, 1948-1949 (New York: Hokubei Shimpo, 1948), pp. 4-5.

4. Ibid., p. 6.

*This article was originally published in the Japanese American National Museum Quarterly, Summer 1998.

© 1998 Eiichiro Azuma