I know, I know, I’ve written about Jack Muro before!—Jack as the “Underground Photographer of Amache,” “Jack Muro’s Photo Album,” and Jack being “Patriotic After All,” but Jack keeps inspiring me to write yet another essay for the JANM Discover Nikkei website.

I was getting ready to leave his and his wife Kate’s home following a successful telephone conference call interview of Jack, conducted by Denver George Washington High School students: Maureen McNamara, Haelee Chin, and Alex Barone-Camp. These same highly motivated high school sophomores contacted and interviewed me the week before. Their National History Day project for their U.S. history class was about one of the ten, WWII War Relocation Authority concentration camps. Their project focused on the one near Granada, Colorado—Amache. They learned about Amache, Jack, and me from their research and reading some of my essays on the above mentioned JANM Discover Nikkei Journal.

I was at 93-year-old Jack’s home to assist Jack with his speaker-phone interview. On the way out afterwards, I mentioned how well his newly planted foot-tall cacti in his front yard seem to be doing. He asked, “Have you seen my backyard garden?” I said, “No,” so he said, “Follow me.” He led me back inside through his kitchen and swung open the backdoor. My jaw did the proverbial drop! His large yard was one story below and filled with a vast desert scene packed with a multitude of cacti!

I expressed surprise—expecting maybe a Japanese garden. He said, “It reminds me of the desert-like Amache!”

When I left, I drove around the block to see his garden from the street behind his lot and took a few more photographs of his striking cactus garden.

Jack’s statement about Amache percolated in my mind a few days and I knew I had to talk with him about what I thought he said, “Amache-desert.” I called and asked if I could come by. He’s always welcoming and he said, “Yes.”

He said that Amache was bleak like a desert when they first arrived in late ‘42, which was bulldozed bare for the construction of the camp buildings. The normal terrain, a desert range of a variety of plants including: sage, rabbit brush, Russian thistle (Tumbleweed) and a sprinkling of prickly pear cacti, which can be seen on the outside perimeter of Amache even today. Now, it is growing back inside.

Photos I took in 2008, show (L) the remaining footings for the Amache water tower* and the terrain outside the camp perimeter and photo (R) shows a prickly-pear cactus amongst other plants.

Many of the Amache internees, mostly Californians, who had backgrounds in farm agriculture and floral nurseries began to enhance their bleak environment by planting trees and gardens. Most Amacheans regularly referred to their Amache surroundings as the desert, as does former Amachean, artist Lily (Nakai) Havey in her upcoming (2014) book, “Gasa Gasa Girl Goes to Camp.” Her book, filled with her art, photographs, and her touching story of growing up in Amache will be introduced in a JANM public program, most likely in September 2014.

(To read more about Lily Havey >>)

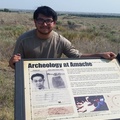

Dr. Bonnie Clark, University of Denver anthropology professor relates how her long-term and ongoing archaeology surveys of Amache, conducted every two-years since 2008, is proving the anthropological need for making a place, even a concentration camp, more homelike. “The archaeological study of landscape is a powerful tool for understanding placemaking as an anthropological phenomenon.”

Dr. Clark in her contributing chapter, “Cultivating Community: The Archaeology of Japanese American Confinement at Amache” for a book titled, Landscape, Memory, and the Politics of Place, wrote:

“Located on the High Plains of Colorado, the area is characterized by wind and little rainfall and the on-site soil is almost entirely Aeolian deposited sand. The region had been hard hit by the dust bowl and at the beginning of World War II was just beginning to recover. Despite the delicate nature of the soil, the WRA bulldozed the entire site prior to construction. As a result the internees arrived in a moonscape devoid of any vegetation and characterized by nearly constant, gritty winds.”

“Internees almost immediately set to changing the situation. Trees were transplanted from the Arkansas River, located three miles north of camp, or later purchased from an enterprising local nursery, which sold them to internees for 50 cents each.”

Jack Muro and his family lived in block 6H and their block proudly produced an elaborate community rock garden, as partially seen behind a group of 6H girls in a 1943 group photograph. Gift of Jack Muro, Japanese American National Museum (2012.2.561)

Here is another partial view of the 6H garden that Jack photographed with his friend: Taro Tanji,(L) and two unidentified internees standing nearby. Gift of Jack Muro, Japanese American National Museum (2012.2.586)

Block 6H would celebrate their Bon Odori, community dance in memory of their ancestors around their rock garden, the focal point for many social rendezvous. Gift of Jack Muro, Japanese American National Museum (2012.2.601)

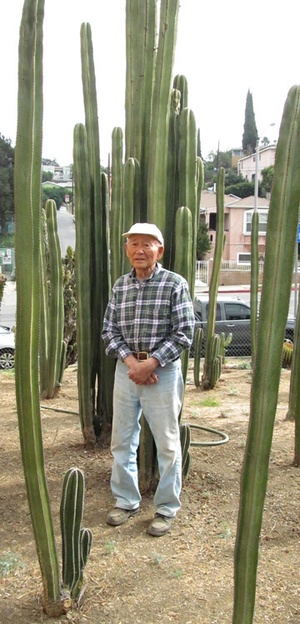

Jack said of his cacti garden, “I wasn’t really trying to re-create the Amache landscape,” and said of his garden, “It only reminds me of Amache a little.” Jack said he liked the deserts and often took Kate and their two children, Allen and Jeanne, in their RV to places like the Anza Borrego Desert, Joshua Tree National Park, and Death Valley. Jack started to buy cactus and bring them home to plant in his garden ever since. He said, “I’m a lazy gardener, I just plant the cactus and water it a little bit and off it goes! I don’t have to water them as much as needed for other types of garden plants.” You might call this Jack Muro’s “platemaking.”

Today, Jack stands proudly among his huge cacti. He said, “My neighbors think I’m crazy, but I don’t care what they think, I love my cactus garden.”

* Click here to see how the water tower is being restored and re-erected at the Amache site >>

© 2014 Gary T. Ono