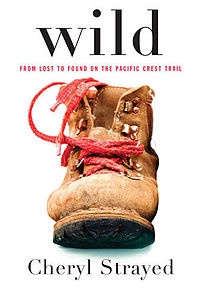

I recently read Wild: From Lost to Found on the Pacific Crest Trail, a memoir by Cheryl Strayed. Wild tells the story of Strayed’s 1,100-mile solo journey along the Pacific Crest Trail (PCT), a hiking and equestrian trail running from Mexico to Canada along the ridge of the Sierra Nevadas and Cascade Mountains. Devastated by the death of her mother and reeling from the implosion of her marriage, Strayed spends the summer of 1995 on the PCT searching for healing and redemption.

Strayed’s 3-month journey takes her from California’s Mojave Desert to the northern border of Oregon; from a woeful beginning with an absurdly overweight backpack she can barely lift (which she affectionately calls “Monster”) to being hailed as the “Queen of the PCT.” Through chance encounters with kind strangers, fellow PCT hikers, and the occasional bear, Strayed ultimately finds herself again (while losing a few toenails along the way).

Wild has met with wild acclaim. The memoir was named Best Nonfiction Book of 2012 by The Boston Globe and Entertainment Weekly and chosen as the Book of the Year by NPR, spent 38 weeks on the New York Times bestseller list, and is an Oprah’s Book Club pick. Strayed’s brutally honest voice and her story of vulnerability, loss, love, and courage clearly resonates with a lot of people. Yet as I read, I felt a rift emerge between me and the author. I finished the book feeling a strong sense of alienation from Strayed’s narrative, that whoever she was talking to, it wasn’t to me.

About 3 weeks into her hike, record snow levels on the High Sierras force Strayed off the PCT. She makes an unanticipated stop in Lone Pine, California to bypass the snowed-in portion of the trail; she had originally planned to push on to Independence, 50 trail miles to the north.

I felt a rush of recognition as I read those town names. Between Lone Pine and Independence, in the shadow of the High Sierras, lies the site of the Manzanar concentration camp, where over 11,000 Japanese Americans were incarcerated during World War II. I had been to Manzanar last summer, stayed at a hostel in Lone Pine, and walked along the same main street Strayed did as she figured out her next move. So I was incredibly disappointed that Strayed made no mention of Manzanar at all. She learns from another character that Lone Pine was the set of the movie High Sierra with Humphrey Bogart, but of the historic site that once held so many wrongfully imprisoned Americans a few miles north, there was nothing.

It hurt, knowing that a significant landmark of my community’s history—of American history—was so close, yet so completely forgotten and invisible, undiscovered and unacknowledged. It was a painful reminder of the way Asian Americans continue to be marginalized by being pushed slightly out of frame, whether due to ignorance or because we are considered irrelevant to the conversation.

Perhaps Strayed saw no reason to weigh down her bypass storyline with a tangent about Manzanar. But it does a disservice to all Americans to suggest that Asian Americans aren’t part of the broader social and historical fabric of our country, or that our stories hold no meaning outside our self-contained community. Of course it is not the responsibility of an author to tell everyone’s story, particularly in a memoir. Yet by leaving Manzanar out of the narrative, Strayed bypassed an opportunity to build a richer context and a more inclusive story.

The Manzanar bypass represented a broader issue I had with Wild, which was Strayed’s utter blindness to her own white privilege. Her lack of critical consciousness regarding her race was especially disappointing given how acutely aware Strayed was of the dangers of being a woman hiking alone in the wilderness. Near the end of her journey, she reflects, “All the time that I’d been fielding questions about whether I was afraid to be a woman alone—the assumption that a woman alone would be preyed upon—I’d been the recipient of one kindness after another… I had nothing but generosity to report. The world and its people had opened their arms to me at every turn.” Indeed, Strayed’s journey was filled with kindness of strangers. She is picked up for rides while hitchhiking between the PCT and campgrounds; she is invited into people’s homes to eat, shower, and rest; she is given free food and shelter when she runs out of money.

Strayed does not bother to analyze her reception beyond marveling at the open generosity of those she meets. While she occasionally concedes that being a woman is advantageous for her in some ways, she totally fails to acknowledge the ways in which her whiteness mitigates the risks posed by being a woman. She remains oblivious to the impact the intersection of her gender and race had on her experience on the PCT.

Halfway through her hike, Strayed refers to Monster as “my almost animate companion… I was amazed that what I needed to survive could be carried on my back. And, most surprising of all, that I could carry it.” Yet part of the reason Strayed could survive with just the contents of Monster was because she also carried the “invisible knapsack” of white privilege, described by Peggy McIntosh* as “an invisible weightless backpack of special provisions, maps, passports, codebooks, visas, clothes, tools and blank checks.” Being white granted Strayed access, and provided her a sense of certainty and security that the world is made for her and will accommodate her.

Perhaps it is a unique conceit of writers to think their individual stories showcase universally applicable truths about human nature. But it is troubling when the very foundation of a story rests on a privilege not afforded to everyone. Had Strayed been a woman of color, her journey along the PCT would have been a very different experience, and Wild would have been a very different book.

*Peggy McIntosh is an American anti-racist activist and feminist, currently teaching at Wellesley College. Her article “Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack” is considered a seminal work on white privilege.

© 2013 Christine Munteanu