Read Part 5 >>

Keeping B.C. “White Only”

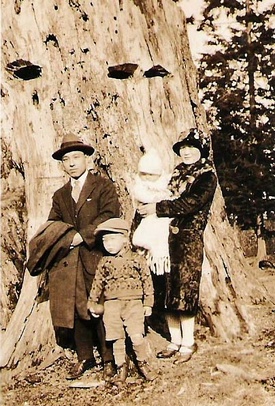

Long before the war, there was an ongoing KEEP B.C. WHITE ONLY outcries—such racial hatred especially along the B.C. coast where the Japanese Canadians were concentrated. When I kept hearing this over and over, even at my young age I knew that it just wasn’t right and had a premonition that something terrible would be coming up. I didn’t feel at ease at all. In fact, it was scary!

The Caucasians really believed that “whites” were a superior race inherited through their forefathers and tried to brainwash us into believing it also!

Many higher professions were denied to JCs as they didn’t want competition and we were treated as second class citizens and then into a “nothing” when the war started. Even after completing and obtaining certain degrees JCs were not accepted in the workplace to suit whatever they graduated from so they had to settle for menial jobs. There were “problems”—Japanese were very industrious hard workers, sometimes working for lower wages and of course their bosses liked them (more production with lower wages) and that’s simple economics. The fishermen came from fishing villages of Japan and were experienced in using their superior ingenuities and out-performed the locals. There were many working in the mining and forestry industries but I didn’t hear much about how the JCs were affected in those fields.

The locals didn’t really know the Japanese as they didn’t associate with them much due to language barriers. There’s this competition and a threat so the locals attacked with racial hatred grouping them as one terrible “Yellow Peril” taking their jobs away—that’s simple basic psychology. They think the worst of each other. It’s always been the case even today. The “Keep B.C. White Only” racial hatred was also happening towards the First Nations people, East Indians, Chinese, Blacks, etc. during that time.

Even countries cannot and do not talk to each other, think the worst of each other, and have wars which are still ongoing. I don’t know how many years before the war—but in Vancouver, the Caucasians used to terrorize J-town and Chinatown which were side by side, breaking all their showcase windows and destroyed or ransacked their goods on Halloween nights I heard. One year, the judo and kendo clubs were waiting for them and that put a stop to the terrorization, the elders said. All I can say is what a human attitude/behavior problem there was, just unbelievable!

Labelling JCs “Enemy Aliens”

When we were forced into internment camps, I felt sorry for all the honest, dedicated, and loyal people who ran the store, especially Mr. Hayashi who wasn’t even a blood relative. He was like more than an uncle to me, and his daughter, Chiyoko-san who lives in Kelowna now, was close to us as well and she still calls me Fumio-chan and treats me like her little brother even now. I still call her Chio-chan like when I was a little child.

Adding a “-san” after a name is showing respect and is quite straightforward and formal but adding a “-chan” is showing love and closeness towards a child, child towards an adult, or between children but can carry on towards their adulthood and is a little more complex. They all went through many hardships and successes together and did good things for the JC community but ended up with nothing. They just said, “shikataganai,” talked only about the good memories, and moved on. You can’t find those types of people now in this era, that’s for sure.

If I was at the store, I would sometime remind my father that he’s late for his meeting at such and such time but he always said, “Oh, don’t worry, it’s only about an hour since it was to start, they won’t start without me.” Apparently, that’s the way it was with everybody involved in J-Town and the meetings wouldn’t start until maybe two hours later. No wonder Dad came back home from work very late at night sometimes.

Talking about the old days in Toronto with Mr. Hayashi, he told me that both Dad and Tokio-san were easy going gentle people, too nice and people were forever asking them to lend them money and both never were able to say no and dished it out easily—good P.R. men he called it. He doubted most of it was ever paid back, especially when the war started. He was trying to teach me a lesson telling me that if a borrower has no intention to pay back, when you see him walking towards you on a street, he would cross the street and walk on the other side looking away from you. Mr. Hayashi was the first person to teach me that if one has an excuse, it will never get done. I guess he was telling me that “that guy who went walking across the street” was an excuse too. He indicated that at least one truck (cube van) was always on the go for transporting baseball teams, picnic use, and all sorts of functions.

It seemed to me that Mr. Hayashi was the fatherly figure of the store and I guess there had to be somebody around to operate the business in a reasonable fashion. I already noticed that my father always thought about others before himself as he would tell my mother that he hasn’t eaten yet after he came home from work late but he’s going to Hasting Park to drop off some Japanese food stuff that the impounded Japanese people would be missing. I tagged along sometimes too. Dad had many late, late suppers until the government set up a curfew against the JCs only.

We lived at 2690 Cambridge St. and there was another Mr. Hayashi, a Japanese Consulate and his family living on the opposite corner of the street. My sisters used to play with their children and were always going back and forth.

All the rest were Caucasian families. During the Depression, my father bought a double lot and had a two storied house built on it. I think it was built by Japanese construction people complete with a custom made Japanese style bathroom, “Nihonburo” and the pretty landscape which had a Japanese touch was done by a Mr. Bando—his name I remember.

When the war started and we knew we had to move away, my father had everything moved down to the basement play room and had it locked up before renting the house out. He rented it out cheaply to an Anglican minister thinking that everything would be safe until he returned. He thought that the war wouldn’t last long as Japan was just a very small country fighting the whole world. Little did he know that the war would last until 1945 and we wouldn’t be allowed to go back to Vancouver and the government sold off our house without our permission.

When Dad found out that all the men over 16 would have to go to road camps, he and Mr. Hayashi’s son, Katsuzo-san, who also worked at the store, got in Dad’s car and fled to his friend, Mr. Yamaoka, who had a farm and orchards in Kelowna. I remember that time as the RCMP came to our house the next day and came asking for Dad to be taken away to work in a road camp. We were all outside clinging to Mom’s skirt and frightened as Mary was interpreting for Mom. I think the Mounties picked him up later as we were all together again on a ferry to Squamish and then on to the PGE train to Bridge River to be interned.

© 2013 Frank Maikawa