Waking slowly. I can still remember the exquisitely warm feeling of waking up at home in my bed upstairs. The sounds floated up from the kitchen and gradually I began to distinguish the voices of my mother and father and older sister, Connie. It was a murmur accompanied by the clatter of pots, the hiss of water, the dull thud of the thick wooden cutting board being set upon the counter. New Year’s.

The preparation for New Year’s started days in advance. In fact our tradition for Christmas was to order Chinese food from a Cantonese restaurant 30 miles away in the city so that my parents and Connie wouldn’t have another big meal to prepare. Often we had company on New Year’s, the one and only time we had strangers in our house. My mother invited Japanese emigrants who had somehow wandered into her workplace, bachelor Nisei bowling buddies of my uncle, and a war bride whose husband had left her years ago. “Poor Mrs. Hawthorne. Twelve years and still hasn’t told her father in Hokkaido.”

I remember coming down the stairs, hearing their voices and the sounds of their cooking, and when I entered the kitchen the three of them were there at the table or at the sink or stove. My mother and sister wore aprons, their faces flushed and wisps of hair curled about their foreheads. My father wore a white T-shirt and khakis and one of his old blue post office shirts unbuttoned. As a child, then as a teenager, and finally as a young adult home from school, or on vacation from a job—through all those years it always seemed the same.

On New Year’s Eve we ate black beans for good luck, and on New Year’s morning there was mochi, charred and puffy and served with a sweet shoyu. It burned the roof of my mouth.

There was teriyaki and what we called “chashu.” My father spent hours grilling plates and plates of chicken and pork that he turned with a pair of foot long chopsticks. And there was tempura. My father said when he was a boy the sweet potatoes were like candy, and it wasn’t until years later that it became true for me, too. Every year he and Connie worked on their technique to get the shrimp to lie perfectly flat. My father cursed them, a constant delight for the rest of us. My older sister talked to them, about them, in a childish jargon she had adopted that belied her expertise. “Big boy goes near little boy.”

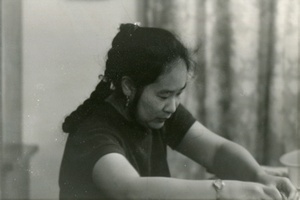

Connie helped, too, with the complicated details for my mother’s futomaki. Then my sister dropped the childish guise and stood with hands on hips, ready without need of a prompt to hand over the next ingredient. Fat rolls she wrapped in wax paper and placed so precisely, so carefully in long white cardboard boxes—shirt boxes my mother had saved for that purpose.

There was a huge red snapper that unlike the shrimp could not lie flat, but was trussed so that after cooking it had a pleasing flip to its head and tail. Sharing the center of the table along with the snapper was a platter of mysterious vegetables, some dark as though soaked in shoyu, some round like a wheel with spokes. There was sashimi and little platters of kamaboko and ginger and pickles—not the homemade pickles from our garden, but fancy store bought ones from the Star Market downtown.

My mother used the giant serving platters she inherited from my grandmother and the translucent china we were all afraid to wash for fear of chipping the delicate dishes. Cups and saucers that all year were kept wrapped in tissue paper so old it was soft as skin now were set not for the every day Lipton bags, but the earthy aromatic loose leaf tea from the tall tin my mother kept on a high shelf.

And there was rice. Of course. Lots of rice. Before the time of rice cookers it was my only cooking lesson. “You can tell by the smell when it’s done,” she said.

And now I wonder why was that my only lesson. What was I doing all the time they were cooking? When I think of all this food, all this preparation, it was my older sister who helped and learned and thereby understood the value. Even after my parents died, she continued the traditions, though each year more and more items were dropped off the list. What once was a meal that took up all of the table and counter tops had shrunk down to chicken and rice and tea. I was no help then either, and even tried to avoid this sad little meal. I didn’t understand the need to continue it. How is it my sister did?

Connie was developmentally challenged, retarded was the diagnosis at the time. She suffered much from the world outside our home, and as she aged she ventured out less and less. In a rare confession, rare because my mother believed that strength of character was measured in endurance, weakness in complaint, she told me she had once visited Connie at school. In a sea of teenagers and loud voices my sister sat in the cafeteria at an empty table and ate alone.

“I peeked in and saw all the other tables crowded with boys and girls, and there she is all by herself. Nobody at her table. The teacher says that’s how it always is. Always. Imagine.”

I thought I was smarter than Connie; I lived in a big world with all the options I had seen on TV while her world, I thought, was embarrassingly small—my parents, the family, the house, our home. But when I think of her at New Year’s, when she was a young adult chattering on in that make believe guiless innocence, confident and strong, I realize she knew then what I was slow to learn.

They are all gone now, and I spend New Year’s in the past and not the future, and though there is pleasure and comfort in remembering my family and our traditions and food, there is sorrow, too, in the realization of what is lost, what it finally came to mean, my waking slowly.

© 2013 Barbara Nishimoto