Late one evening, early in May 2002, I sat in a hotel room with a colleague, historical archaeologist Nicole Branton, after a long day of traveling and conducting interviews. Together, we read from the wartime diary that Joe Norikane had so generously lent to us. We had visited Joe and his wife Tee as a part of the California Civil Liberties Public Education Program grant we had received to conduct oral histories with Nisei who had served wartime federal prison sentences in the Tucson, Arizona, “honor camp.”

In 1999, the Coronado National Forest had renamed the site of the former prison in honor of its most famous prisoner, Gordon Hirabayashi. During World War II, Gordon Hirabayashi had served a ninety-day sentence when he lost his Supreme Court case challenging curfew and the West Coast exclusion orders. Much to his dismay, the Supreme Court only considered the issue of curfew, and decided unanimously that even a racially written curfew order was not unconstitutional in a time of war. Hirabayashi would have to wait until 1987 to have this personal conviction overturned when the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals determined that racially written laws were unconstitutional always, even in a time of war. As a small consolation after the disappointment of losing his case at the Supreme Court level, the district attorney allowed Hirabayashi to hitchhike to Tucson where he could serve his ninety-day sentence in a road camp instead of being stuck inside a county jail or penitentiary. Forty-one other Nisei also served 6 month to one-year prison terms in Tucson in 1944, the following year, for refusing to be drafted while both they and their families were being held without due process in a War Relocation Authority concentration camp.

In an effort to understand more about both Gordon Hirabayashi and the draft resisters, Branton and I traveled to California to conduct oral history interviews, and to attend the JACL’s public ceremony apologizing to the resisters and acknowledging their wartime courage to stand up for their rights as citizens. The evening before the JACL ceremony, Branton and I read the diary Joe Norikane kept from 1943 through 1944. We thought that its pages might reveal the idealistic mindset of a young man preparing to take on his government in a courageous act of civil disobedience. What we found instead was a book chronicling Norikane’s doubt and insecurity not about the war, the draft, or his civil rights, but about a girl. We read page after page about his social life, sports, and a whole lot of dancing.

When we met with Norikane the next morning to record an interview, he apologized for not having written about more important issues in his diary. We assured him that our impression was quite the opposite; because he wrote about the most important issues he had faced personally as a young man despite the extraordinary circumstances in which he was living. He recorded the life of a young man coming of age, and it was the ordinariness of his reflections that we valued the most.

Norikane, like the rest of the Nisei draft resisters, along with others who resisted their wartime treatment in other ways, did not resist in a vacuum. His resistance represented a nuanced choice to defend his citizenship rights that he believed could not be divorced so easily from his obligations. As Norikane sat down to be interviewed about his life and his resistance, he recalled that when he was in jail with some of the other resisters from “Amache” in Colorado, none of them believed that they would get a fair hearing or that their struggle for civil rights would be remembered. For decades they were forgotten, but Norikane always hoped that the stand he took in defense of his constitutional rights during the war might someday be recognized. If he left “a footstep in the sand of time,” Norikane said, “somebody might look back on what was going on during the war and get curious.” By the time Norikane died in the spring of 2003, he had left several footprints in the sand of time, and every year since then more and more people have been curious about what his resistance meant during the war and what it means to us today.

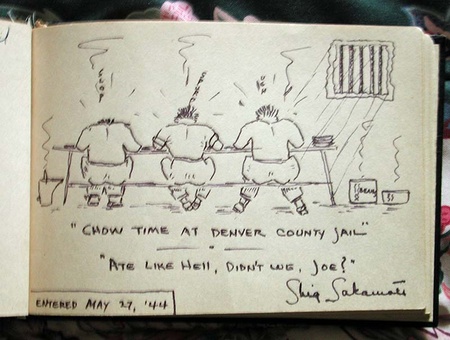

Cartoon drawing in Joe Norikane's autograph book, 1944. Photo by Jeff Burton, courtesy of Jeff Burton, 2002. This cartoon is a depiction of life in Denver County Jail.

Joe Norikane’s diary helped frame my research for the next several years. In the first year of World War II, Nisei lost their citizenship in symbolic and practical ways. Selective Service reclassified them as “enemy aliens” despite the fact that they were American-born citizens. The Western Defense Command of the Army had euphemistically called them “non-aliens” in official proclamations ordering all persons of Japanese Ancestry to “evacuate” their homes and turn themselves over to the War Relocation Authority. The War Relocation Authority held them, along with their parents, under armed guard, without due process. It was under these conditions that the War Department restored only the obligations of Nisei citizens, first by asking all adult Nisei to register using the Selective Service’s form titled “Statement of American Citizens of Japanese Ancestry,” and later by reinstating the draft.

Historians have often separated the loyalty questionnaire from the reinstatement of the draft, as if they were separate events. But through my research, I found clearly that both the War Department and Japanese Americans considered these two events to be linked together. The loyalty questionnaire as it has come to be known was the first step in restoring the draft, and Japanese Americans responded to the registration crisis by asking tough questions about the War Department’s decision to recruit Nisei men into segregated combat teams while their rights as citizens remained uncertain. It is no coincidence, for example, that the Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee first organized in response to the loyalty questionnaire and only later, when concerns had not yet been resolved concerning the status of Nisei citizenship rights, the Committee became the largest single organized group of draft resisters in U.S. history.

Through my research, I found that all of the various forms of resistance that normally were treated separately if at all by historians were intimately connected. When the registration program was announced in Topaz, Utah, for example, the first questions Japanese Americans asked were about the segregated units being created for the Nisei, about the likelihood of a draft, and about the vague promises of Nisei citizenship being restored someday, but not yet. Issei warned younger men to be cautious in accepting promises that their rights would be restored and their citizenship “rehabilitated” only after they demonstrated their willingness to serve in a segregated army. Issei reminded the Nisei of their own experiences fighting during WWI and the years that it took to force Congress to grant Issei veterans the citizenship promised to them before they served. Discussions were organized where Issei, Nisei, and Kibei alike could ask government representatives hard questions, and when their questions were not answered, they organized resistance that stalled the registration process, and tried to force the government to restore Nisei citizenship rights before Nisei were asked either voluntarily or perhaps later involuntarily to perform the most onerous obligation of citizenship: combat duty in a war. Seen in this way, it became clear to me that resistance to the draft started early and took many different forms. It was only in 1944 when the draft had been fully restored for Japanese Americans that protest for some transitioned into criminal acts of civil disobedience.

Instead of treating “No-No’s” and renunciants separate from others who protested the unconstitutional nature of wartime policies, we should consider what the various forms of protest and civil disobedience accomplished as a whole. In 1944, when the first five men refused to appear for their pre-induction physicals from the Amache concentration camp in Colorado, the WRA community analyst there was asked to explain what had become a crisis situation from the point of view of the camp administrators. Why were so many families requesting repatriation to Japan? Why were growing numbers of Nisei renouncing their citizenship? And why were young men not reporting for their pre-induction physicals? The analyst explained that having grown up with discrimination their whole lives, the wartime treatment of Japanese Americans had only reinforced the idea that they would never get a fair shake in this country. It was the perceived unfairness of their treatment that had unleashed overwhelming and creative forms of protest and even acts of civil disobedience. But protest and civil disobedience did not have anything to do with loyalty, he argued. Other notable figures agreed. J. Edgar Hoover agreed. Instructions came down from WRA headquarters to all of the camps that seemed to indicate that the War Relocation Authority agreed, too. Renouncing one’s citizenship in the spring of 1944 would no longer be grounds for being removed to the Tule Lake Segregation Center. It would instead be taken as an attempt to avoid the draft. At Amache, this meant that the five young men who had already been sent to Tule Lake were on their way back to camp despite the fact that they had renounced their citizenship and requested repatriation to Japan. They would have to face the draft just like every other Nisei in Amache. The sheer numbers who protested their wartime treatment forced the government at various levels to reinterpret their protest not as evidence of disloyalty, but as evidence of their dissatisfaction with their lack of rights. The government’s ability to use simple questionnaires to define individuals as loyal or disloyal had backfired, and by the spring of 1944 it had seemingly become nearly impossible to determine who was loyal and who was disloyal. Tule Lake had become so overcrowded as to make it impractical to send anyone else to this one “segregation” facility. Instead, camp administrators turned their attention to promoting patriotism and compliance with the draft by inviting war heroes to tour the camps, by supporting carefully orchestrated memorial services for fallen soldiers, and by encouraging Japanese Americans, particularly local supporters of the JACL, to dissuade young men from joining the growing numbers of draft resisters through personal persuasion and intimidation. The young men who went to prison for resisting the draft during the war were not alone in their opposition to their unconstitutional treatment, even though they were ostracized by members of their own communities and were deliberately erased from history for a time as if they represented an outside minority.

As more and more time passes, we can see with greater clarity the footprints Joe Norikane and others left behind. Our ability to interpret acts of civil disobedience improves with time. Joe Norikane did not intend to become a civil rights hero. He did not want to be honored by the JACL in 2002. As he put it, he did not need an apology. He knew all along that he made the decision that was right for him during the war. He did not need anyone’s approval then, and he hesitated to attend the JACL’s reconciliation ceremony toward the end of his life. But he did attend. He was pleased to help young people, the Sansei and Yonsei generations, understand that they can stand up for their rights.

Joe Norikane’s oral history is housed at the Japanese American National Museum along with interviews with Gordon Hirabayashi, Ken Yoshida, Susumu Yenokida, Harry Yoshikawa, and Noboru Taguma.

Group photo in front of mock interpretive panels planned for installation at the Gordon Hirabayashi Recreation Site, Tucson, Arizona. Back row, left to right: Hideo Takeuchi, Joe Norikane, Ken Yoshida; front row, left to right: Harry Yoshikawa, Noboru Taguma. Photograph courtesy of Ken Yoshida, 1999.

© 2012 Cherstin M. Lyon