Seventy years ago this week, 425 men from California entered a detention camp in Santa Fe, New Mexico for the first time. As prisoners of the United States Department of Justice, their hands were bound behind their backs, but by any legal measure they were innocent.

Their only crime was their heritage: Japanese. As leaders of Buddhist churches, teachers of Japanese language, or business owners with ties to Japan, the FBI had been spying on them months before the Japanese military attacked Pearl Harbor. On the night of December 7, 1941, arrests began.

While Americans may generally know the U.S. government incarcerated Japanese Americans from the West Coast starting in February 1942, far less is known about the Department of Justice-run camps, and even less is known about the peculiar practice the U.S. government undertook to pad these prison populations with people living in South America.

During World War II, more than 2,000 people from South America were forcibly deported to the United States.

Congress should act to pass Senator Daniel Inouye’s bill (S. 64) to create a commission that would set the record straight about how the United States made these extraterritorial arrests, blatantly ignored the rule of law, and essentially imported prisoners to be used as pawns in future hostage exchanges with Japan.

Inouye, a decorated World War II veteran who literally gave his right arm in service to our country before becoming our first Japanese American in Congress, calls the commission bill “a matter of honor”. “It might be painful, but I think we should go through the process of learning how bad we were,” he said in an interview for the documentary Prisoners and Patriots.

A bill to create a commission on the U.S. treatment of Japanese Latin Americans passed the House Judiciary Committee with bipartisan support last Congress, and was temporarily included in a major appropriations bill (HB 2112) this Congress, but 70 years after the opening of the DOJ camp in New Mexico, the only thing our government has officially said about the dubious arrests in South America is a 14-page annex tacked on to the 1983 report, Personal Justice Denied, issued by the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians.

We know from that report that the U.S. gave Peru $29 million dollars in arms in a lend-lease deal that was among the biggest in the Western Hemisphere, and we know that Peru sent more prisoners to the United States than any other South American country. “Bribery may have been involved,” in determining who was arrested in Peru as well, the report said.

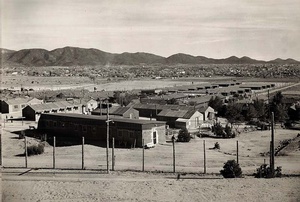

Most of the male prisoners spent some time in Santa Fe, where at times they made up 13 percent of the population. Alongside them were U.S. citizens, many stripped of their citizenship because they stood up for their civil rights at a time when few others would—refusing to serve in the U.S. military as long as their families remained behind barbed wire.

Congressional action today cannot correct past civil rights abuses, but a government-published report could help to make up for bureaucratic entanglement that has resulted in inadequate preservation of historic records and thus more questions than answers about the DOJ camps and their Japanese Latin American prisoners.

“They were not part of the war. They didn’t know what the United States was all about, and we just plucked them off the streets.” Sen. Inouye told me. “That’s not the way a democracy runs, even in war time.”

At least 800 Japanese Latin American prisoners were sent to Japan in exchange for American hostages in 1945.

For all the contemporary debate about Guantanamo Bay and administrative detention, and the recent speech by Attorney General Holder defending the government’s execution-before-trial policy for U.S. citizens who allegedly aid the enemy, a report on how our country justified making arrests without due process in 1942 would have all the more interest.

When President Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, granting $20,000 and apology to every survivor from the War Relocation Authority camps, the Japanese Latin Americans got nothing.

Ten years later, the Clinton Justice Department settled a case brought by five Japanese Latin Americans seeking their own redress for the government’s actions. Under the settlement, 600 people received apology letters and $5,000.

“It’s time to right this wrong and close the book,” Attorney General Janet Reno said that day.

Unfortunately, the government never wrote anything on the pages to explain its actions toward Japanese Latin Americans during the war.

Note: The anniversary date is March 14, 1942.

* * *

There will be a free screening of Neil Simon's film, Prisoners and Patriots: The Untold Story of Japanese Internment in Santa Fe, at the Japanese American National Museum on Saturday, April 14, 2012 at 2:00pm. Q&A with the filmmaker to follow screening.

The DVD is available from the Museum Store >>

© 2012 Neil H. Simon