Read Part 6 >>

Born Free and Equal: Differing Interpretations

In the late 1970s three graduate students in the UCLA Fine Arts Program created an exhibition and book called “Two Views of Manzanar,” which included photographs by Adams and Miyatake. Graham Howe, who along with Patrick Nagatani and Scott Rankin, opened the show at UCLA’s Frederick S. Wight Gallery in October 1977, praised Adams’s work at Manzanar in an interview as “his most compassionate body of work.”

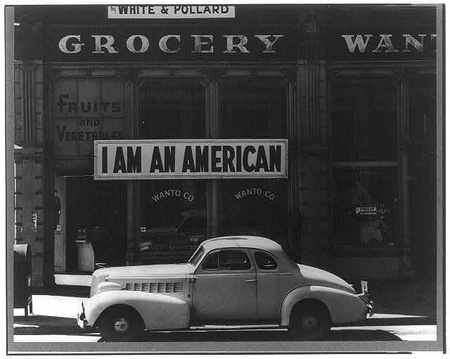

Not everyone viewed Adams in such a heroic light, though. The same year that the “Two Views of Manzanar” exhibit was mounted, the writer and critic Karin Becker Ohrn compared Adams unfavorably with Dorothea Lange in an article in Journalism History. Ohrn called Adams an “apologist intent on showing the success of the internment,” and his pictures “insights into the officially sanctioned view of the internment at the time.” By contrast Lange, the critic argued, typically adopted the “antagonist position,” attempting to create images that revealed the injustice of the mass roundup and imprisonment of the Japanese. As an example, Orhn cited Lange’s photograph of a large sign in the window of a Japanese-American grocery bearing the words “I AM AN AMERICAN,” a plaintive cry drowned out by the calls for incarceration. For the lead photograph of her article, Ohrn chose Lange’s portrait of nine members of the Mochida family, dressed in their best clothes and tagged like pieces of luggage, waiting for the bus that was to evacuate them from Hayward, California.

Lange's photographs, like this one of a sign put up by the UC-educated owner of a San Francisco store, underscored the injustice of Japanese American incarceration. (Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA)

In their 1988 book Manzanar, constitutional lawyer John Armour and Associated Press photo editor Peter Wright introduced Adams’s forgotten prison camp photographs to a new generation. They described an Adams motivated by a sense of social justice but whose message was out of sync with the prevailing war-mongering sentiment of the times. In a long essay in Manzanar, John Hersey called Adams’s Born Free and Equal an appeal to the conscience of America: “The book’s implicit message of guilt and shame did not go down well with a public still hungry for the unconditional surrender of a tenacious enemy. Copies of the book were actually burned in public ceremonies. The book hid itself away in the rare-book rooms of libraries and on microfilm. Adams eventually declined to renew the copyright on it and gave the negatives and prints of his photographs to the Library of Congress.”

Critic Judith Fryer Davidov, however, in a fall, 1997 article for The Yale Journal of Criticism, “The Color of My Skin, The Shape of My Eyes: Photographs of the Japanese-American Internment by Dorothea Lange, Ansel Adams and Toyo Miyatake,” took Adams to task for glossing over the uglier aspects of Japanese prison camps and the fundamental injustice of incarcerating people because of their Japanese ancestry. Davidov noted that Adams’s photographs of “accommodationist Nisei—those who demonstrated their submission to captivity by working to make the spaces in which they were imprisoned more comfortable and attractive, or their patriotism by enlisting in the armed forces—fit perfectly with the official presentation of the concentration camps as humane, orderly, and even beneficial to the internees.” Imprisoned Japanese-Americans, Davidov wrote, “are posed against the familiar redeeming mountainous terrain to suggest the mythic possibility of transcending adversity.”

Born Free and Equal Influences: Dorothea Lange and Carey McWilliams

Adams’s Manzanar photos were to undergo yet another reversal in critical interpretation with the mounting of the show “Ansel Adams at Manzanar” at the Honolulu Academy of Arts and The Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles in 2006 and 2007. In her deeply sympathetic catalog essay, Adams expert and curator Anne Hammond traced Adams’s influences in the making of Born Free and Equal. Hammond portrayed an artist too old to fight, yet seized by the desire to contribute to the war effort, his views shaped by artists and thinkers who shared a liberal, anti-incarceration bias. As one of those influences, Hammond cites Dorothea Lange, who urged Adams to make haste with the Manzanar project, writing:

Now is the time, not six months or a year from now, because the situation is constantly shifting and I fear the intolerance and prejudice is constantly growing. We have a disease, this Jap-baiting hatred. You have a job on your hands to do to make a dent in it—but I don’t know a more challenging nor more important one.

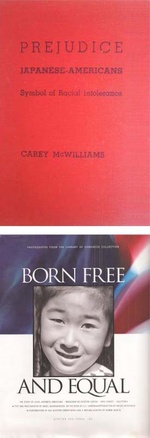

A book by lawyer and crusading journalist Carey McWilliams[above] defending the civil rights of Japanese Americans informed Adams's views in his own book, Born Free and Equal[below].

Lange also introduced Adams to the writings of Carey McWilliams, a lawyer, journalist and defender of migrant workers, internees and other progressive causes. According to Hammond, Adams relied heavily on McWilliams’s work, especially his book, Prejudice: Japanese-Americans, Symbol of Racial Intolerance, while writing Born Free and Equal.

One of the oft-cited phrases in Born Free and Equal by critics who label Adams an “accommodationist” is his characterization of the concentration camp as “Only a rocky wartime detour on the road of American citizenship…a symbol of the whole pattern of relocation—a vast expression of government working to find a suitable haven for its war-dislocated minorities.” Reading McWilliams’s 1944 pamphlet on the forced exclusion, What About Our Japanese-Americans (a copy of which, according to Hammond, was in Adams’s library), I realized that Adams had clumsily lifted the phrase from McWilliams.

In his pamphlet, McWilliams made a persuasive case for trampled rights of the imprisoned Japanese Americans and argued that the U.S. government could redeem itself by rewarding the loyalty of the interned Issei (who had been barred from becoming U.S. citizens) with the chance of citizenship after the war. If this happened, and the imprisonment ended soon, McWilliams wrote, “It may be justified as an extension of democracy and not merely defended as ‘a harsh but necessary’ impairment of the democratic process. We need not apologize for the program as ‘detour from democracy,’ for it has a strong democratic potential.”

Adams condensed and simplified McWilliams’ subtle and diplomatically worded thought. By adding the word, “only” to his description of the camps in “only a rocky wartime detour on the road of American citizenship,” he implied citizenship was guaranteed to all Issei as payment of their suffering. Sadly, the government did not heed McWilliams’s advice and the imprisonment of the Japanese was not tied to the reward of citizenship. It was not until the passage of the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1952 that Asian immigrants gained the right to become U.S. citizens.

Although McWilliams suggested the U.S. government could redeem itself by offering prisoners citizenship, Japanese immigrants were not given that right until 1952. (Source: Gift of the Saburo Toyama Family, Japanese American National Museum [97.208.1])

© 2011 Nancy Matsumoto