>> Part 2

I thought about my father, his absence, his distancing. He was an apparition that appeared briefly and disappeared over and over from my life. Like my mother, he grew up in a small rural hamlet tacked on to the fringes of a larger city. Both ended their formal educations in the sixth grade, but the similarities end there. She took on family responsibilities; he emigrated to America.

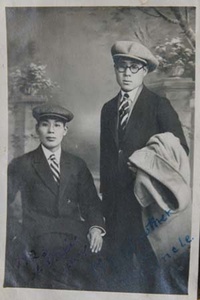

Author's father (right) and his uncle Chonozo who raised him. This was taken on the eve of her father's departure to the U.S.

My brother and I called him “Daddy.” So did my mother except when she was exasperated or angry at him...then it was “You, anta.” My aunts called him “Neesan,” Elder Brother. He was “Kay,” sometimes “Ken” to his friends. His real name was Kanesaburo but no one, not even his parents used it. They knew him only as the stranger-son they had left in Japan as a newborn. His mother was only sixteen and escaped to America with her lover after giving birth. He was raised by his uncle Chonozo and his family.

“Your daddy didn’t like the inaka, countryside. He ran away to Wakayama City a couple of times. His uncle found him the first time and they made him watch the family eat, but wouldn’t feed him. He didn’t tell me much more. I think it was too painful. Poor Daddy,” my mother told me.

I imagined this little boy, perhaps nine or ten, sometimes hitching wagon rides, but mostly walking toward Wakayama and resting, tucked against trees and fences. How far twenty miles must have seemed. How happy he must have been to reach the Pacific Ocean, and then wonder how he could cross that vast expanse to a place called Ka-ri-fo-ni-ya and find his parents. His uncle assured him that his parents would send for him one day.

On his second attempt he actually found a job for a month as an errand boy at a small family restaurant and lived in a tiny space in the back between sacks of rice. Before dawn he accompanied the owner to the fish market and learned how to choose the best of the catch...“alert” eyes, shiny skin, fresh ocean smell. And the shape, yes, the shape had to be perfect. If the fish were deformed in some minute way...missing scales, a clipped fin, or a strange color, these were obake, hobgoblins, and would bring bad luck to the restaurant. My father learned how to brew fine green tea...the water was boiled to the “tiny bubble” stage. He heard the water sing in the iron kettle before the bubbles burst. If he were only a few seconds early or late, the tea would not “accept” the water. He learned to prepare vegetables for pickling, pressing down the slices in brine with wood and stones.

He was so happy. The owner told him that as he learned the trade, he would pay my father a few coins. But one day there he was...his uncle stood over him as he straddled the hole in the backyard. My father quickly pulled up his pants and without a word, his uncle led him inside to gather his meager belongings, and they trudged home in the gathering dark. This time, however, they shared the rice balls and pickles that the owner had hastily packed for them.

When he was twelve my grandmother Fusa returned to Japan to escort my father to California. He attended public school but there were no provisions for immigrant students and he found himself herded into a second grade class. Humiliated, he quit on the spot. He must had had a flair for calligraphy or art, however, because the few letters I remember my mother receiving from him were written in English with great flourishes.

His life, however, was bereft of ornaments. He struggled with job after job. Remembering his aborted but happy experience in the restaurant, he opened a small cafe in Los Angeles, but without business expertise, it floundered. He discovered that alcohol could erase his frustrations, and once hooked, he could not climb out of the deep abyss it created.

“Poor Daddy,” I agreed with my mother. And so it was that we both accepted into our lives this man who came and went, ghost like, in our lives.

* * *

One afternoon in July some mess bells began to sound in the middle of the afternoon. I ran home to find my mother standing immobile outside our barrack door. She grabbed my arm and pushed me into our room.

“What’s wrong? What’s happening?!” I cried.

More mess bells clanged in confusion. The distant wail of a siren moaned through the din.

“What’s going on?”

“I don’t know. Mrs. Satomura said some trouble makers are rioting. They make trouble for all of us.”

“What do you mean?”

“We come to camp. No trouble. We do like the government wants. No trouble. If we gaman. If we endure... there’s no trouble, but some people are trouble makers.”

“I want to go see.”

“We need to stay inside. Be safe. Be safe.”

“Everyone’s out there.”

“I will take care of you. Nothing bad will happen to you.”

“I can’t do anything exciting just because I’m a girl.”

“In Japan girls don’t look for excitement. They take care of the family.”

“Mama, this isn’t Japan. It’s America.”

“America,” my mother murmured, and looked out the window as if “America the Beautiful” were a picture hanging outside the camp.

“This is America,” she repeated.

Then to my astonishment, my mother began to cry. Softly, quietly, at first...then a keening, heaving wail. She sank onto her bed.

I didn’t know what to do. This was my mother. This was the woman who was always strong. She knew what to do, how to handle everything. She was the one who carried on whenever my father disappeared. Now I heard the cry of a lost child, a soul wandering down some meandering path with no light at the end.

“Mama? Don’t cry,” I whispered, but she didn’t hear me. Her sorrow was overwhelming. She sobbed until her tears were used up. She groped for me and I sat down by her side. She reached for my hand. She gripped it so hard it hurt.

“You know,” she whispered.

“What?”

“Maybe I would do same thing.”

“What do you mean?” I was scared. I had never heard anyone cry like this before.

“I would be a troublemaker.”

“You?”

“I made trouble for father in Japan.”

Author’s note:

This is chapter 3 from an upcoming publication titled “18286.” The watercolors, photographs, and pictures which accompany each chapter, and are an integral part of the manuscript, are not included here. I have freely used dreams and imagination to augment lapses in memory, but the episodes are true. I have researched events and dates of historical events for accuracy.

© 2010 Lily Yuriko Nakai Havey