“Study history. Learn about yourselves and others. There’s more commonality in all our lives than we think… There is so much that unites us, which we do not learn.” Malcolm X (from Heartbeat of Struggle)

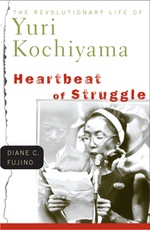

One of the most important human rights activists of the past 60 years is the 88-year-old American Nisei, Yuri Kochiyama, who is the subject of Heartbeat of Struggle, a compelling 2005 work by Diane C. Fujino, associate professor of Asian Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

I first heard about Kochiyama some time ago. She is the Nisei lady who was a friend and supporter of the great Black Muslim leader Malcolm X Shabazz who, after being expelled from the Nation of Islam in 1964, was assassinated on Feb. 21, 1965 in the Audubon Ballroom where he was scheduled to give a speech. Yuri is the lady who held Malcolm X as he lay dying in the famous Time magazine photograph.

This important critical study introduces this Nisei activist to new generations and details the remarkable activism of Yuri Kochiyama beginning with the internment of Japanese Americans during World War Two, the Civil Rights Movement in the U.S. and work to free political prisoners like David Wong and Mumia Abdul-Jamal.

This is a fascinating chronicle of the evolution of a revolutionary thinker and activist who helped guide the civil rights struggle in the United States from the time of the incarceration of America’s Japanese population during World War Two, the aftermath of the war and the subsequent rise of the civil rights movement and up to the height of the 1960s revolution during which time Yuri was in the vortex of the movement. Fujino does a splendid job of giving the reader a multi-dimensional portrait of this modest lady whose seems to have been drawn into human rights struggles almost despite herself at times.

Kochiyama’s (nee Nakahara) story begins on a positive note as her family was a successful immigrant family living in a thoroughly middle class life in San Pedro, California, south of Los Angeles. They already achieved the American dream: living in a middle class home, comfortable, in a mostly white neighborhood. Yuri was a 20-year-old Christian Sunday School teacher and her twin brother, Peter, volunteered to serve in the U.S. Army immediately at the outset of America’s joining the during World War Two. Her parents, Seiichi and Tsuyako (nee Sawaguchi) Nakahara, immigrated from Iwate-ken, Japan. When President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on Feb. 19, 1942, American’s west coast population of 120,000 Japanese Americans was rounded up and placed into concentration camps for no other reason than they were non-white descendants of an Asian country against whom the United States was at war. Despite the media flamed hysteria, no evidence of espionage, sabotage or fifth-column activity on the part of any Japanese American was ever found.

We are introduced to Yuri’s as a 20-year-old Presbyterian Sunday school teacher who already was demonstrating leadership qualities. The day of Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor happened to be a Sunday and when she got home from church the FBI was already at her house to arrest her father, Seiichi, because of his own leadership role in the Nikkei community. Yuri’s father was imprisoned in a federal penitentiary on Terminal Island where he became sick. His crime was being a community leader who sold fishing and marine supplies to Japanese ships that docked at San Pedro harbor. Afterwards, no longer even able to speak, he died in 1942 at home. He was 54.

The Nakahara family was first incarcerated in the Santa Anita Assembly Center in California where, the family was forced to live in livestock stables. They were then transported to the Jerome, Arkansas, concentration camp. The complexities involved in Kochiyama’s evolving sense of self of who and what she is as a Nisei began in the concentration camp where she began to learn about and appreciate the virulent American racism that put her own people behind barbed wire.

Amidst the war hysteria, the governor of Arkansas, Homer Adkins, refused to allow the Japanese to work, relocate or attend college in Arkansas outside of the concentration camps. In the state there were even complaints that internees “ate extravagant food, led leisurely lives, and lived off the government.” Ironically, what was to become the most highly decorated battalion in the war, the 442nd Regimental Combat Battalion made up mostly of Nisei, was training at nearby Camp Shelby, Mississippi, where racial hatred, even towards non-whites in uniform, was rampant. Black GIs who were stationed in Mississippi, couldn’t walk on main streets in the South, even in uniform, Yuri learned later.

After the war in 1946, Yuri and Bill, both 24, were married and living in New York City. They eventually settled in a three-bedroom government subsidized apartment in the Amsterdam housing project in mid-town Manhattan, a predominantly Black residence, where they would live for the next 12 years. In 1960, with the arrival of their sixth child, they moved to the Manhattanville housing project in Harlem.

This move elevated Yuri’s consciousness as it put her in the proximity of Harlem and close contact with Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) leaders, the Harlem Parents Council (HPC) that organized the largest boycott in US history and opening the first Freedom School in 1963; involvement with the Black Power Movement; the Asian American Movement in the late-60s; the Japanese American Redress Movement, among many others.

In addition to raising six children with husband Bill, a soldier with the famous “Go For Broke” 442nd Battalion, Kochiyama worked mostly as a waitress and secretary. Bill worked in the public relations field in New York City where he had grown up as an orphan. The entire family was actively involved in some of the twentieth century’s most important civil rights movements, including Redress.

The story of Yuri’s connection with Malcolm X is a well documented one and transformational in her life as an activist. She first met him in 1963 and corresponded with the great leader even after he was expelled from the Nation of Islam, forming his own Muslim Mosque, Inc. afterwards. He is even shown in a picture attending one of the Kochiyama’s gatherings at her home in 1964 when a group of hibakusha, survivors of the Hiroshima atomic bomb, were visiting New York City.

By the mid-70s, in addition to her activity with the Black Power movement, Yuri became involved with the Asian American Movement. The Asian Americans for Action (AAA, pronounced triple-A) was first conceived by two Nisei women, Kazu Iijima and Minn Matsuda, in NYC in 1969. The movement was against American’s involvement in the Vietnam War, arguing that “corporations are financing a war to create new markets and develop a cheap labor force, at the expense of democratic rights of Vietnamese people.”

Bill, who was most active in the Japanese American Redress Movement, passed away on Oct. 25, 1993 at 72. At 75, Kochiyama had a stroke in March 1997. Yuri moved to Oakland, California in 1999, where she resides today.

Her message continues to be a timely one: “The United States has gained support for its wars by using media to whip up war hysteria. During World War Two they demonized the Japanese; today they are demonizing Muslims and Arabs. And just as the war against Japan … resulted in racial profiling and internment of Japanese in America, the ‘war on terrorism’ has resulted in the racial profiling and detainment of Arabs, Muslims, South Asians and all people of color living in the United States today,” Kochiyama said in a 2002 War Times interview.

By the end, the reader will be a little breathless at the remarkable breadth of Yuri’s activism. Kochiyama’s life work finally reminds us that we as a Nikkei community should never be complacent when it comes to recognizing our collective responsibility to continue to help those who struggle for human rights, at home or globally, and that the need to work for the “togetherness of all people” is as great now as it has ever been.

Yuri Kochiyama: Heartbeat of Struggle by Diane C. Fujino, 2005, University of Minnesota Press ($19.95 US)

© 2010 Norm Ibuki