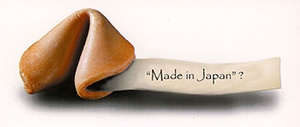

The fortune cookie, the famous and fun gratuitous dessert, is unfailingly gifted following delicious meals in all Chinese restaurants throughout the world. So this uniquely sculpted cookie with a personal message tucked inside just for you must be Chinese, right? The Chinese must surely have invented and own the fame and fortune associated with it.

Early on I did not question this widely accepted assumption, even though my late 1940 through 1950 childhood memories included watching such fortune cookies being produced in my grandfather’s Japanese confectionary shop in San Francisco’s Japantown. I remember them being made with a huge carousel-like, heat spewing baking contraption.

Until approaching adulthood, rarely did flashback images of fortune cookies being made by my Grandfather Suyeichi Okamura’s Benkyodo Company prompt me to ponder the remote possibility that the Fortune cookie might really be Japanese!

When we grandchildren became old enough, as kind of a rite of passage, we were invited to help in the Benkyodo family’s annual production of mochi (cooked, pounded sweet rice-cake). Mochi is a food staple key to Shogatsu, the New Year’s celebration by the Japanese. Reporting for work at the crack of dawn, we’d sleepily walk past the idle “merry-go-round” like machine—inactive because during the weeklong period between Christmas and the New Year, mochi production became Benkyodo’s main focus. We’d head back to the steamy, warm room anticipating the cherished close family bonding that surrounded us during those ensuing days.

It was during those times we first heard tidbits that our Ojiisan (grandfather), or Jiichan as we called him, was linked to the origin of the fortune cookie. It was even imagined that he might have invented it!

Growing up, I became more interested in Japanese American and family history and that curiosity heightened during the 1970-1980 period when the movements for redress and reparation began. It was a time when, for Asian Americans, like for the Blacks (African Americans), ethnic pride and confidence was growing in strength.

Some of us younger members of the Ono and Okamura families grew more interested in the story that tied Jiichan to the fortune cookie. One of my six sisters, Teresa introduced me to two well-established San Franciscans, Sally (Noda) Osaki and Tomoye Takahashi, both Nisei who she got to know through the Japanese American Community Cultural Center of Northern California. She said they seemed to know a lot about Japantown history and Jiichan’s business in the Japantown community. She was right and did they ever!

Encouraged by their gracious generosity in sharing their experiences and knowledge, I felt more confident to attempt to tell this story about our grandfather. I felt compelled to share what I’ve learned and hope, in some format, to add it to the pages of a still growing Japanese American history as more stories are revealed. To accomplish this task, I worked with the staff at the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles who were interested in my project for use in a future exhibition.

In San Francisco, in addition to Sally Osaki and Tomoye Takahashi, we interviewed Erik Sumiharu Hagiwara-Nagata, a great, great grandson of Japanese Tea Garden founder Makoto Hagiwara, who is often cited as the one who introduced the fortune cookie in the Tea Garden in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park.

We also interviewed my Auntie Sue Okamura and two of her four sons, Ricky and Bobby who continue to operate Benkyodo, the manju-ya (Japanese confectionary shop) which recently celebrated it’s centennial. Ricky and Bobby dedicated the Centennial to their late Jiichan Suyeichi and recently deceased father, Hirofumi “Hippo” Okamura.

In Los Angeles we interviewed Roy Kito and his son, Brian, who is now the third generation owner operator of Fugetsudo, a Little Tokyo Japanese confectionary. Little Tokyo is the Los Angeles equivalent to San Francisco’s Japantown. Roy, now deceased, said he and his father knew my Jiichan and Uncle Hippo Okamura. Today, Brian knows my cousins, Rick and Bobby Okamura and are on friendly terms with them.

Following are three presentations, which I believe will support what strongly appears to reveal the true origin of the fortune cookie in America:

The 1983 San Francisco Court of Historical Review (Mock Trial)

Sally Osaki was the Administrative Assistant to San Francisco Supervisor, Louise Renne, when Bernard Averbuch, President of the San Francisco Boosters, solicited Superior Court Judge Daniel M. Hanlon to hold a Court of Historical Review to settle, as Averbuch stated, “the classical confrontation between the cities of Los Angeles and San Francisco” each claiming, among other things, their city as the site where the fortune cookie originated.

Judge Hanlon consented to convene the 1983 “Mock Trial,” which was full of good-natured bantering that ensued from both sides. Attorney Frank Winston, who was appointed to represent the Los Angeles claim wore a Mandarin robe and cap and spoke in a “Charlie Chan” dialect. Judge Hanlon, appointed Supervisor Renne to represent San Francisco. Renne recognized early that her administrative assistant, Sally Osaki knew quite a bit about the San Francisco fortune cookie history and so made her a key witness. Sally put a lot of effort into organizing a convincing case for San Francisco.

One of Sally’s strong pieces of evidence, among many, was the 1983 letter hand-written by George Hagiwara, grandson of Makoto Hagiwara, the 19th century founder and caretaker of the Japanese Tea Garden in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park. George Hagiwara wrote:

My grandfather, Makoto Hagiwara introduced the fortune cookie at the Japanese Tea Garden between 1910 and 1914 before the Panama-Pacific International Exposition of 1915.

My family made the senbei by hand in iron skillets over a charcoal fire and folded the senbei while it was still warm. We were the first to put in fortunes written in English.

My grandfather attempted to make a mechanical fortune cookie maker but was unsuccessful. Around 1918, my grandfather contracted with the Okamura family who owned the Benkkyodo (sic) Confectionery store to make the fortune cookie for the [Japanese] Tea Garden.

Our family continued to sell tea and fortune cookies in our teahouse concession until we were removed from the Japanese Tea Garden in 1942 and interned for the duration of World War II.

Another account that Sally presented was in a letter from Kathleen (Fujita) Date. To Sally, she wrote:

You are on the right track about the fortune cookie. My parents were good friends of George Hagiwara’s grand parents and his accounting of the fortune cookie is true. Makoto Hagiwara did bring the first fortune cookies to the U.S. from a Japanese Temple and had an arrangement for exclusive rights in the U.S.

Date also related to Osaki, an early 1920’s story told to her by her mother. Osaki presented this same story at the 1983 trial and during a videotaped interview in 2005:

Kathleen Date told me that her mother and five other women were having lunch in a small restaurant in an alley in Chinatown. And, after their lunch one of the women had brought along fortune cookies and so they were opening the fortune cookies and they were laughing and giggling and having a good time and a Chinese businessman who was sitting nearby came up to them and wanted to know what they were having such a good time about. And so, they told him.

And then a few weeks later, Mrs. Date’s mother, whose name is Fujita, saw this same man leaving this confectionary story in Japantown. It was called Shungetsudo. It was at the corner of Sutter and Buchanan, she said. And he was leaving the store with this big, they used to sell these sembei in these big tin and he was leaving the store with a big tin of them.

And she said, after that, often they would go to that same confectionary store to buy sembei; they would say that they were out because the Chinese were buying them all up.

And then she said that she would later notice that Chinese restaurants were serving the fortune cookies after meals and that the fortunes were in English.

Sally Osaki did some additional pre-trial work. She went cookie shopping in Japanese and Chinese confectionary stores throughout San Francisco. Her conclusion, presented at the trial, was that cookies (sembei) in various shapes and sizes were all made with the same ingredients used to make fortune cookies and were found only in Japanese confectionary stores and not found in any Chinese stores.

Sally also exhibited an antique sembei iron kata (hand skillet), loaned to her by the Hagiwara family. It was actually used in the Japanese Tea Garden to hand-make the fortune cookies one at a time.

The Los Angeles primary claim of origin was that a noodle factory owner, David (Tsung) Jung invented the fortune cookie in order to feed and inspire the homeless in 1924. Phillip Choy, a self-proclaimed Chinese American historian stated:

...the Japanese are good at adapting and improving ideas they take from the Chinese, like art, language and customs...the Chinese invented the fortune cookies long before the Japanese did.

Unfortunately, and I don’t know the reason, but Fugetsudo of Los Angeles was not involved in this trial. If he had been, Brian Kito would have stated that he believes that his grandfather Seichi, who co-founded Fugetsudo in 1903, came up with the Fortune cookie. However, I believe that like us Benkyodo kids, Brian and his siblings heard stories that suggested that their respective grandfathers “invented” the fortune cookie. In reality, neither Benkyodo nor Fugetsudo can conclusively prove their beliefs. In the spirit of fair play, Brian even says, “If Fugetsudo didn’t invent the fortune cookie, I hope it was Benkyodo.”

Umeya Rice Cake Company founded in Los Angeles was also producing fortune cookies early on, but was also not a part of the Historical Review Trial.

Even without Fugetsudo and Umeya’s participation in the trial, Judge Hanlon had had enough. He ruled emphatically that the ethnic origins of the cookie were indeterminate and said, “matters of the East, we should leave to the East.” He delivered his verdict in favor of San Francisco to “deafening” cheers from the spectators. The line “leaving matters to the East” turned out to be prophetic as will be evident later in my story.

© 2007 Gary T. Ono