Read part 1 >>

Section 2: Repatriation

The second section featured a major drama of the exhibition, from the time when the relationship between the U.S. and Japan began to decline until the end of WW2, entitled “Immigrants and the Outbreak of War Between the U.S. and Japan —Anti-Japanese Movements, Incarceration and Repatriation.” Although the section covers a long period with important historical events, the narrative relied on the presence of the Repatriation Ships to show the dynamism of the movement of people.

At the entrance to this section, the audience was informed about the shifting status of Japanese by a panel with illustrations and documents explaining the "Yellow Peril"1 and the anti-Japanese movements in the U.S. For example, one thing that caught my eye in the panel was a cartoon of a bad image of a Japanese (Cleveland Leader 1905) as a representation of changing attitudes towards the Japanese due to rising militarism in Japan following the Russo-Japanese War (1904-5). This exhibit showed the many factors that contributed to a series of causes that eventually had negative impacts on the status of immigrants, leading to the so-called Anti-Japanese Immigration Act in 1924.

As I passed through the entrance to this section, I saw a big image of a War Repatriation Ship. I had not known about these ships, and I learned that the operation of the ships at that time was made possible by mediation from the Swiss government. Accordingly, the War Repatriation Ships were operated between England and Japan as well as the U.S. and Japan. Some Japanese on the U.S. mainland must have had hopes to board a repatriation ship in order to return to Japan after the outbreak of the war. In addition to the operation of these ships, the exhibit explained that people waited for the arrival of the ships because they used the empty space to bring food and materials, such as shoyu and green tea, before taking people on board. There was also a photo of captured people with these Japanese groceries in the exhibit.

Moreover, to bring visitors to a greater understanding of the subject of the Repatriation Ships, this section included a documentary film entitled Memories of the Repatriation Ships on a touch screen. In the film, Kiyoko Takeda, a female philosopher who came back to Japan on a repatriation ship, talked about her experience, allowing visitors to understand more fully the reality of these ships.

The exhibit further explained the movements of Japanese immigrants on the U.S. mainland after the outbreak of the war. The earlier part of this section showed the lives of people in incarceration camps, including many photos taken at the Tule Lake, Heart Mountain, and Santa Fe detention camps. This exhibit noted that many young male Japanese had joined the 442nd Regimental Combat Team.

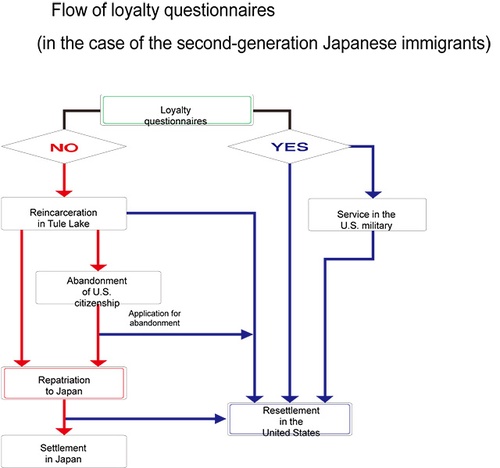

The later part of this section was entitled “Incarceration and Repatriation” and showed the two paths of Japanese Americans, either living as American citizens or returning to Japan, after answering loyalty questionnaires as internees. The most significant item for me was a diagram introducing life in an internment camp, to let the audience understand the sequence of movement after 1942 (Picture 1)2. The diagram caught my eye since it clearly showed the two currents of movement with two colors in the form of a flowchart. The concept emphasized the flow of people from these camps — one way, staying within the jurisdiction of the U.S., and the other way, going back to Japan. In other words, these were the people who answered “yes” or “no” to No. 27 and 28 loyalty questionnaires3.

Flow of loyalty questionnaires: Click to enlarge (Copyright: The National Museum of Japanese History).

However, I noticed one characteristic of the narrative. In the past, even in Japan, the lives of people in the internment camps were reported and described in the media because it was a tragedy. But this exhibit focused equally on the people who left America and the people who lived as American citizens. In fact, many Japanese saw a Japanese TV drama entitled Japanese American 99 nen no ai (2011), featuring some people who joined the 442nd Regimental Combat Team and gave their lives to elevate the status of Japanese Americans during World War II. For the Japanese audience in Japan, this drama must have shed light on the story of these male Nisei, but it said nothing about the group of people who went back to Japan and struggled to resettle there.

The exhibit showed the process by which people denied their loyalty questionnaires and returned to Japan on the repatriation ships. There was a Japanese newspaper article praising some Japanese who denied the loyalty questionnaires in the Heart Mountain detention camp. Accordingly, they formed a junior chamber called Houkoku-Seinendan and their spirit was called houkoku (devotion to country). Following this topic, a photo of these Japanese boarding the ship in Seattle for repatriation was displayed.

Under the heading of "people on the move," this section focused equally on the people who left the U.S. on the War Repatriation Ships and others who remained in the U.S. and eventually received redress in the 1990s.

Part 3 >>

Notes:

1. A color metaphor for race that was used in the late 19th century and was applied to Japanese immigrants in the 20th century in Western countries. The massive numbers of Asian immigrants were believed to threaten the country's standard of living and socioeconomic structure.

2. This diagram was made based on a study by Yoko Murakawa (2010), Chusei no imi [meaning of loyalty], Discover Nikkei, http://www.discovernikkei.org/journal/2010/9/6/chusei-no-imi/ Originally, the study was contained in the catalog for this exhibit.

3. In Feburuary 1943, the examination of loyalty to the U.S. that was carried out included question no. 27 regarding willingness to serve in the armed forces of the U.S. and no. 28 swearing to defend the U.S. from attack and forswearing obedience to the Japanese emperor.

© 2011 Kaori Akiyama