Read Part 7 >>

Adams, Paul Strand, and the Nisei Point of View

Hammond also defended Adams’s style against critics who found his photographs lacking in pathos or without political context. Karin Becker Ohrn, for example, in 1977 favorably contrasted Lange’s photos of concentration camp prisoners, who appeared “less controlled even slightly uncomfortable,” to Adams’s, which she deemed more “formulaic.” Hammond found a rationale for Adams’s close-up portraits, many of which are shot outdoors or against the open sky or a non-descript background:

Miss Michiko Sugawara, photograph by Ansel Adams. (Photo: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA)

Most forms of social documentary drew public attention by portraying their human subjects in a state of distress to incite public outrage, but Adams wished to generate recognition on the part of ordinary Americans that the Japanese Americans were in very many ways just like them, that they were not degraded or dejected in their racial difference, and were not expressing outright anger, anxiety or resentment, however justifiable those emotions were under the circumstances.

Hammond also pointed out that Adams’s Manzanar work was deeply influenced by the direct gazes in Paul Strand’s New Mexico portraits. In an article on Strand’s photographs that he wrote in 1940 for U.S. Camera, Adams extolled their superior virtue (“documents in the highest sense of the term”) over texts, which could merely describe the political and social conditions present. Only first-rate documentary photographs such as Strand’s, asserted Adams, could produce the “resonance and mood and assertion of the somber humanity of the people.”

Because Adams’s Manzanar photographs were heavily influenced by Strand’s example, it is instructive to look more closely at the older artist’s body of work; the book Paul Strand: Essays on His Life and Work (Aperture, 1990) is revealing. Though Strand’s first teacher was the pioneering photographer and social reformer Lewis Hine, he was also heavily influenced by the aestheticism of Alfred Stieglitz. As he became more interested in progressive politics in the late 1920s and early ’30s, Strand’s early abstract works gave way to equally beautiful portraits of rural Mexicans, New England farmers, Italian peasants and Irish fishermen, all of which stressed the heroic dignity of the common man. Like the art of the Soviet system that Strand admired, there was no room in his utopian vision for suffering, desolation and obvious social injustice. In her essay, “Praising Humanity: Strand’s Aesthetic Ideal,” the critic Estelle Jussim noted that there is a “superficial resemblance” between Strand’s utopian vision of farmer and peasants and the tractor-driving “happy maidens” and muscular construction workers of Soviet social realism.

Paul Strand's photographs stressed the heroic dignity of the common man, and were a role model for Adams.

Strand’s portraits are imbued with his belief in the artist’s role as one of active engagement, of showing the way to a more enlightened society; they were a far cry from the world of the dishonored and dispossessed that Dorothea Lange portrayed. Yet ironically, Strand was far more reformist in his outlook than Lange. Jussim quoted another critic, Ulrich Keller, who summed up Strand’s philosophy like this: “Everything must be presented as it should be, not as it is, or as it could be.”

Critic John Berger pointed out that Strand depicts the moral contrast between those who are likely to look at his pictures and those whom his pictures depict. Strand left out the misery that mere documentary photographs dwelled upon, Jussim explained, “because he was offering his viewers his conception of human excellence as role models, presenting the strength dignity, and moral superiority of individuals who have not been corrupted by the exigencies of survival.”

In another essay on Strand, Mike Weaver’s “Dynamic Realist,” the author explained that Strand’s brand of realism was by definition “partisan—committed to social change and never defeatist.” In a review of Dorothea Lange and Paul Taylor’s An American Exodus, for example, Strand criticized Lange’s photos for remaining in the realm of social pessimism, merely illustrating Taylor’s text and often lacking “that concentration of expressiveness which makes the difference between a good record and a much deeper penetration of reality.”

Adams’s Manzanar portraits aspire to the expressiveness, heroism and unity of humans and nature that Strand championed. Perhaps, within the context of his unstinting admiration for Strand, Adams’s prison camp photographs can be read as the kind of moral lesson for lesser viewers that John Berger describes. But this style, which Strand pioneered and Adams imitated, has since become a cliché, at least to some. The critic Andy Grundberg, who praised Strand’s earlier, groundbreaking, abstract work, wrote dismissively of a 1991 retrospective of Strand’s work in Washington, D.C., “What happened to Strand in the ’30s happened to many other artists: the romantic, revolutionary appeal of Russian Communism came to represent esthetic progressivism, and thus their art began to devote itself to the kind of ‘common man’ that one encounters over and over again in Strand’s photography.”

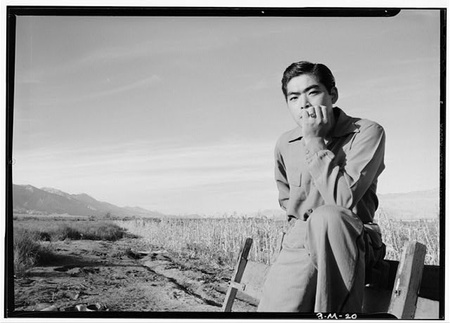

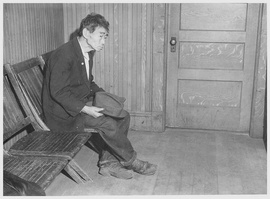

The direct gaze of the dispossessed: Adams's portrait of Manzanar prisoner Tom Kobayashi (Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA)

Adams and the Nisei Point of View

As I re-examined Adams’s photographs, I saw why Nisei like my uncle admired Adams so and viewed his Manzanar work as a humanitarian act. In glossing over the injustice inherent in camp life, omitting Japanese cultural traditions and neglecting inmates’ sorrow and loss, those photographs echoed the Nisei attitude toward camp: a veneer of cheerfulness, a willingness to embrace hard work and a distinctly American brand of civic-mindedness, hiding any pain, anger or shame.

Adams’s photographs mirrored the second-generation Japanese Americans’ desire to prove their loyalty at all costs, to out-American the most blond and blue-eyed citizen and convince the country that they could be trusted enough to be freed. By contrast, Dorothea Lange’s photographs seem to correlate with the angrier response of the Kibei and some Issei to their forced banishment. Her scenes of evacuees tagged like cattle, huddled in long lines, forlornly looking beyond camp confines tell of the prisoners’ humiliation and sorrow, the longing for home in Los Angeles, Sacramento, Seattle or Japan.

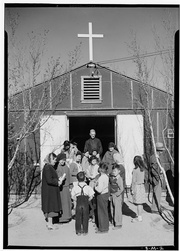

Entrance, Catholic chapel, photograph by Ansel Adams. (Photo: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA)

Social realism or pessimism? Lange's portrait of farmer Toshi Mizoguchi, who wore an American flag button as he waited to register for evacuation from Byron, CA. (War Relocation Authority Photographs of Japanese-American Evacuation and Resettlement)

© 2011 Nancy Matsumoto