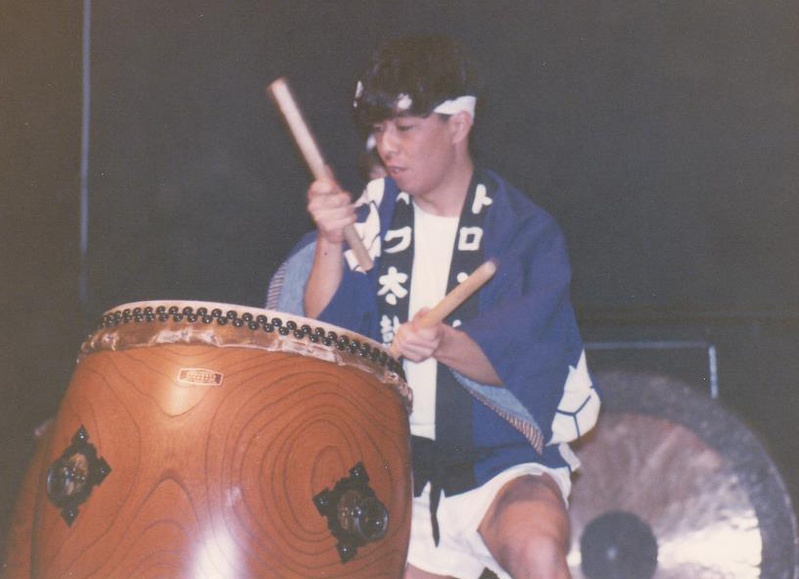

Gary Kiyoshi Nagata, 46, the leader of Nagata Shachu, one of Canada’s premiere taiko groups, was born and raised in the Richmond Hill area of Toronto. The Sansei grew up at a time when the word “Nikkei” was not widely known, “being Japanese” lacked the cultural currency it has today, and when learning about things Japanese required much more determination.

Like Kiyoshi, I grew up in suburban Toronto, but well away from anything Nikkei besides a few other JC families that somehow ended up in the same small rural town. Like Kiyoshi, too, I remember my dad eating thick slices of greasy fried bologna slathered with shoyu on rice, our own brand of chow mein with those dried brown noodles that mom put on top of the veggies and meat to steam, corned beef and cabbage with an egg on top, which, despite appearances, tasted really good.

(I don’t know how pioneer Issei women concocted these recipes in the early days but they managed to bridge the east-west culinary divide with remarkable success. I’m sure that there is a great story there that’s yet to be told.)

Like those early kitchen creations then, Kiyoshi has found a unique and creative way to adapt, evolve, and cultivate a grounded sense of who he is while living and being Canadian. Today, living in one of the planet’s most diverse and open-minded cities, his music while respecting the traditions of taiko, creates remarkable synergies by collaborating not only with traditional Japanese musicians, but also those from other cultures like Korea and India too.

Taiko was, and is, Kiyoshi’s way of connecting with his Japanese heritage as well as who he is as a proud Sansei.

Can we begin at the beginning? How did your parents end up in Richmond Hill?

After the internment, my parents first came to Toronto (they were both around sixteen at the time). Once my parents married, they settled in Richmond Hill in the late sixties where I was born in 1969.

Where were they from in BC? Where were they interned?

My late father was born in Haney, BC and interned in New Denver. My mother was born in Little Tokyo, Vancouver, and interned in Lemon Creek, British Columbia.

Was your upbringing particularly “Nikkei”, e.g., food, music, stories? Did you visit the JCCC? If I ask you to describe yourself as a “Nikkei” what does this mean to you?

I would describe my upbringing as typically Nikkei. For me, being Nikkei sansei meant identifying myself as a Canadian while at the same time being exposed to certain customs and traditions that were both foreign yet weirdly familiar—eating fried bologna or wieners with shoyu for example, as well as a host of homemade Japanese food like onigiri, udon, tempura, sukiyaki, etc. Unfortunately, my appetite for Nikkei food has waned over the years, in favour of more “authentic” Japanese foods including ramen, sushi, and yakitori!

Growing up, I would always hear enka being played in the background and remember visiting ba-chan’s house browsing through her Japanese magazines although I couldn’t read a word of it. I would recall my parents and their siblings fluidly mixing both English and Japanese in the same sentence. All these things gave me a connection to a land I had never been to and encouraged me to explore my heritage and ancestry.

How do you cultivate your Nikkeiness?

Ultimately, my Nikkeiness was cultivated by being engaged in the Japanese-Canadian community where I met many other third-generation Japanese Canadians not unlike myself. As a kid, our family visited the JCCC often and my mom and her sisters danced for O-bon at City Hall every year. I volunteered at the JCCC through most of my youth.

Was this the same for your parents’ generation?

I think for my parents’ generation, it was a slightly different experience. They were the children of immigrants and spoke Japanese growing up. My mother recently told me that she felt a stronger connection to her Japanese side even [though] she had never been to Japan.

What did you think about being JC when you were growing up? How did it affect your sense of being “Canadian”?

In public school in Richmond Hill, I was one of about three Asians in the entire school. I remember clearly telling my mother that I did not want to be Japanese as I didn’t look like the other kids.

What was your relationship with “being Japanese” at a young age?

Throughout my childhood, I recall that although I was Canadian, I was somehow different than most of the people in my town (Richmond Hill was predominantly Caucasian at that time). More than anything else, I wanted to fit in and not be a visible minority.

How much was racism a part of your growing up in Toronto?

I experienced quite a bit of racism growing up. Kids would call me “Jap” or “Chink” for instance. One experience in particular really shook me: I was going for an evening jog in Richmond Hill (I was in my 20’s) when a car pulled alongside me and there were two or three guys in the car. They kept shouting at me “f---ing Jap” in order to provoke me to react so they would have a reason to jump or attack me. It was completely unnerving but I forced myself to ignore them even though my heart was pounding. I went to Bayview Secondary in Richmond Hill and University of Toronto, St. George campus in Toronto where I received a Political Science/Economics degree.

Do you remember when you heard taiko for the first time? What was your initial reaction?

The first time I heard taiko was when I was volunteering at the JCCC during Festival Caravan in 1981. I was about 12 at the time. The JCCC (called the Tokyo Pavilion during Caravan) invited Osuwa Daiko led by grandmaster Daihachi Oguchi from Nagano, Japan. I was completely enthralled by the dynamic and animated performance and by the thunderous sound of the taiko. I was so excited that I would watch every performance they did during Caravan.

What were the next steps in your taiko career path?

Osuwa Daiko’s appearance generated so much excitement, that the following year they invited Oguchi-sensei back to start Toronto’s first taiko group, Toronto Suwa Daiko. Unfortunately, I did not hear about this until they had already formed. So, I did the next best thing, and started taking classes from Toronto Suwa Daiko’s first captain Shingo Kono (who was also the local O-bon drummer) at the JCCC in September 1982.

Were there teachers in Toronto?

Within a year, I was accepted to become a member of Toronto Suwa Daiko and eventually became the group’s leader in 1987. I was with Toronto Suwa Daiko for ten years until 1992 when I decided to move to Japan.

Did your parents expect you to take a more traditional life path? What was their reaction to the choice you made to go to Japan?

I think my parents were hopeful that I would have a good career and settle into a family life in Toronto. My parents always wanted my sister and I to have a good education and prosper, since both of them never went to high school and had blue collar jobs. Nonetheless, they were supportive yet worried of me going to Japan as they knew taiko was my passion and calling.

© 2015 Norm Ibuki