A century ago, the New Year in 1914 brought both promise and uncertainty for Japanese pioneers in California.

Mochitsuki: A New Year tradition, making mochi in Orange County, circa 1926. Cooked rice pounded into a sweet confection still popular today. (Photo snip, Center for Oral and Public History, California State University Fullerton, PJA 050)

It was a time of global social and technological change—affecting state politics—while at the same time generating excitement about what opportunities lay ahead.

In Wintersburg, Charles Furuta and his new wife, Yukiko, had completed construction on their white-trimmed bungalow and settled in to their life as newlyweds. Photos from 1913 show a clothes line with wooden pins behind the house, a lush tree line surrounding the Furuta farm, a stack of wood nearby for future projects, and the Wintersburg Mission and Terahata house among the trees in the northwest corner of the farm.

During her 1982 oral history interview, Yukiko described her home: “It was originally about half the size of the present house, because only two people lived in it. It had a living room, a kitchen, and two bedrooms…There was no electricity, no city gas, and…an outdoor bathroom.” In 2014, the Furuta bungalow remains one of the few Japanese pioneer homes left in Southern California.

Yukiko Furuta holding her first child, Raymond, in 1914. This photograph is thought to be inside the Cole Ranch house in Wintersburg Village. The Cole Ranch was located where Ocean View High School is today at Warner Avenue and Gothard Street in Huntington Beach. (Photo courtesy of Historic Wintersburg and the Furuta family)

By 1914, Charles and Yukiko had been married well over a year and were busy establishing themselves in Wintersburg Village. Yukiko’s expression in photographs from that year is less nervous, more content, now that she had seen more of what her new life in America would be like. She had already seen the bustling cities of San Francisco and Los Angeles, walked the beaches of Long Beach and Huntington Beach, shopped at the Tashima Market and attended services at the Wintersburg Mission.

Yukiko had arrived in Orange County in time to witness the 1913 flight from the Dominguez Hills airfield in Los Angeles County to a farm field in Wintersburg by Japanese pioneer aviator Koha Takeishi. Supported financially by farmers in Smeltzer and Wintersburg, Takeishi would again receive their support in 1914 to participate at the Osaka Asahi airshow in Japan. This would be the airshow at which he lost his life.

The Pacific Electric Railway’s “Red Car” had been humming back and forth between Huntington Beach and Los Angeles for a decade, bringing Angelinos to the beach and making it easier for Orange County’s Japanese community to visit Little Tokyo. As planned, the railroad had prompted more growth in nearby Huntington Beach.

Charles Furuta had already constructed an earthen tennis court on the farm for Yukiko, and he gamely learned to play the sport she had enjoyed in Japan. Also, the year 1914 brought the joyful arrival of the Furuta’s first child, Raymond.

A close-up image snipped from a larger photo of the earthen tennis court at the Furuta farm, circa 1913. Charles Furuta, far right, constructed the court for his new wife, Yukiko. The Terahata house which had been temporarily moved to the farm is in the background. (Photo snip courtesy of Historic Wintersburg and the Furuta family)

Yet, 1914 also ushered in changes that caused anxiety for the growing Japanese community in California. The state legislature had passed the Alien Land Law of 1913 which meant Japanese Issei could no longer buy property. This was the result of a decade of lobbying by labor organizations, like the San Francisco-based Asiatic Exclusion League. In general, there was opposition or ambivalence to exclusion and segregation laws in the southern part of the state. Two U.S. presidents—Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson—had tried unsuccessfully to dissuade discriminatory action by California legislators.

The Great White Fleet parked off Huntington Beach in 1908 before sailing to Yokohama Harbor, in a show of friendship between the United States and Japan. Afterwards, Northern California legislators introduced a series of bills to segregate Japanese immigrant children from the public school system. President Theodore Roosevelt wired California Governor James Gillett to protest the actions as counter to national policy. (Photo, April 18, 1908, City of Huntington Beach archives)

President Woodrow Wilson had sent a friendly message to Japan in 1913, while dispatching Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan to California to plead against passage of the Alien Land Law. He argued it obstructed the treaty obligations of the United States. Juichi Soyeda with the Associated Chambers of Commerce of Japan visited the United States and urged the Japanese and American cultures to attempt to understand each other.

Geraldine Farrar's performance as Madame Butterfly in the Giacomo Puccini opera is featured in a Victrola advertisement in 1914. She had first performed as Madame Butterfly in 1907 with the New York's Metropolitan Opera. Much of the country was enamored with Japanese art and imagery, which influenced popular culture in America. (Image, Wikicommons)

Despite these efforts, California Governor Hiram Johnson signed the Alien Land Law of 1913 on May 19 of that year. Directed at the Japanese, the law also affected Chinese, Indian, and Korean immigrants, while not affecting other non-citizen immigrants.

Attorney and journalist Carey McWilliams—a graduate of the University of Southern California law school—later observed that the country failed to recognize California was part of the emerging Pacific Rim and the failure to forcefully address the prejudices led to failed foreign policy. McWilliams also noted “the southern part of the state and the rural areas generally were not favorable to the agitation.”

In Orange County

As McWilliams described—although there were instances of discrimination—the intensity of exclusion politics was not felt to the same degree in Wintersburg. In farm country and along the Pacific shore, people were working to establish new communities, put in roads, water and drainage systems, and develop new businesses to keep up with services needed by the growing population. In other words, they were busy.

The Japanese community had been a regular part of the Armistice Day and July 4 celebrations in Huntington Beach and Orange County, and had contributed to the fundraising effort to rebuild the Huntington Beach pier. They also would be part of the re-dedication of the pier in 1914, with Japanese fencing and sword-dancing listed on the program right before the surfing demonstration by George Freeth. Members of the Japanese community served on the Orange County Farm Board and had worked with Caucasian and European immigrant farmers battling celery blight. With post office boxes in downtown Huntington Beach, Japanese farmers from around the countryside were part of the community.

The Japanese community in an Armistice Day parade in Orange County in 1926. Parade-watchers lined up along the street and on the rooftops. (Photograph snip courtesy of Center for Public and Oral History, California State University Fullerton, PJA 056)

Despite this, in 1914 northern California congressman John Raker introduced a bill to exclude Japanese from the United States. The U.S. House of Representatives rejected the bill as not being in the national interest. While there were land use covenants restricting where people of color could live in Anaheim and in Los Angeles County during this time, there were none in the Wintersburg Village and Huntington Beach communities.

Beverly Bowen Moeller, the granddaughter of one of Huntington Beach’s first mayors, Samuel R. Bowen, recalled in some hand-typed historical notes1, “…I would walk along the high-crowned oil road past the chili pepper drying houses, past an old wooden derrick with the fields of the small farms belonging to German, Japanese and Italian neighbors,” wrote Bowen Moeller. “Across the street from our house was my favorite place in my small world, the nearly self-sufficient farm of the Armenian neighbors…”

Bowen Moeller describes a predominantly immigrant community, integrated and distinct. For farm country, the politics of 1914 were known, but a world away from the reality of their daily life.

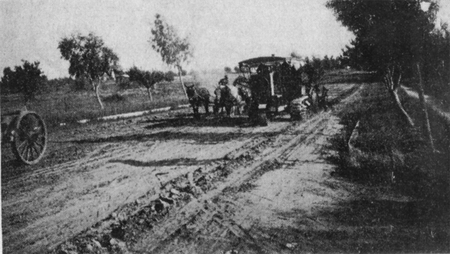

Road grading with horse-drawn equipment in the area of present-day Farquhar Park, Lake Park and 13th Street in Huntington Beach, circa 1912. In 1914, much of Huntington Beach and all of Wintersburg Village was unpaved, country roads; grading was a welcome improvement. (Photo, City of Huntington Beach archives)

Note:

1. Beverly Bowen Moeller, Fifty years ago in Huntington Beach, 1984, Orange County Archives.

*This article was originally published on the Historic Wintersburg blog on January 26, 2014.

© 2014 Mary Adams Urashima