Read Part 8 >>

During the early Internment days, as Shig joined the Canadian Army, Dad asked him to check out his house when he got to Vancouver. Shig called back and indicated that the good Rev. broke into the playroom and was using anything useful, furniture and all. Soon after the government auctioned the house off and sent a fraction of the amount it was worth (a drop in the bucket) to Dad to be used for our Internment living—“Very nice of them,” he said sarcastically and also he used the word “shikataganai” (It can’t be helped. No sense arguing about it because they have the power and we don’t have any say. They’ll just slap you down again if you open your mouth). The Issei used “shikataganai” for many instances such as when they were bringing up their children, as at certain stages it’s no use lecturing the kids over and over because they are not listening so they would give it another try later after they mature a bit more.

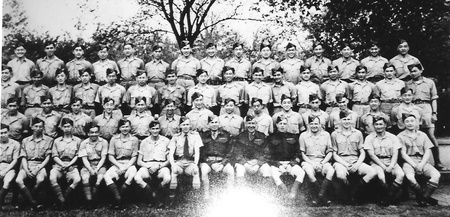

Intelligence Corps, #17 Platoon BCOY #20 CI(B) TCCA Brantford ON. Photo was displayed in old Ottawa War Museum in 2000. They threw this out when new museum was built later.

My mother used to say that over lecturing is harmful as kids’ minds are just growing and when they start to rebel that’s a danger sign, so let it rest—they will eventually come around.

As for Katsuzo-san, he was not interned (he must have slipped through the cracks somehow) and eventually married Mr. Yamaoka’s daughter, Shizuko, then bought an orchard in Oyama and his father, Mr. Hayashi, moved there too to help him. Katsuzo-san later got an opportunity to buy part of Mr. Yamaoka’s orchard and ended up in Kelowna again.

What did my siblings and mother go through those days in Bridge River? We didn’t talk very much about what was happening. But my older sisters, Mary and Sumi were talking seriously with Mom and Dad and they were involved in making decisions to move from here to there until we got to Toronto. My younger sister Amy and I were too young and were kept out of the picture. We were just followers and nosy too so I knew what was going on.

One other specific thing I can remember: My mother told me to write a letter to Mrs. Wells, my former grade 3 teacher in Vancouver to let her know that I was now in an internment camp in Bridge River so I did write and my teacher was surprised. Her letter back to me was censored by the government. I remember one sentence I wrote was—I have to stop writing now as Mom is calling me for supper and I’m hungry as a bear. She always wrote back and told me that she read out my letters to the class and used it for teaching purposes and that “hungry as a bear” was used too. I guess she was trying to cheer me up and I knew I wasn’t up to speed in education with only half day schooling.

My mother continued to teach Amy and me the Japanese language though while our friends were playing outside and seeing them through the window made it very hard to concentrate. But, I’m glad I learned the language as I was able to communicate with the Issei to learn and was also so useful when I visited Japan a few times later in life.

In Bridge River, there was a public school 100 feet away from us but we weren’t allowed to attend. There were Aboriginals living nearby also but they weren’t allowed either and had to go to their own school. The locals however, invited us and the Aboriginals once to participate with them in a Christmas Concert at the Community Centre and that was good of them. We didn’t have any Caucasian friends but just JCs only, mainly cousins and most of the Maikawas were there. Some friends were from Steveston and I used to enjoy learning and talking their Kishu-ben Japanese dialect. Before we got to know them, they called us “Bunkuba no Chunkoro”—name calling.

We learned “G-language” (it was used in all the internment camps. You just insert “G” into appropriate places like this: Higai Norgormugusagan, Igai agam vergerygi thagangfugul togu yougu forgo yourgo hegelp. Googoofigi, eghay?) there too and it became a habit, slipping up sometimes talking to teachers and parents.

Alan Fujiwara, Dr. Fujiwara’s son, although a couple of years older than me was a good friend too and we all did many things together like fishing (although we weren’t allowed to); skating; swimming; kayaking; softball; basketball; making slingshots and using marbles at first then graduating to deadly steel ball bearings and we did some awful things which I don’t want to confess; we went on many long hikes around our close-by mountains too.

Alan was an excellent drawer and even made his own comic books expressing his imaginary stories mainly. I wasn’t surprised to find out that he became a famous artist later because he had much talent from his childhood days. We did a lot of bad things too like one neighbour had a chicken coop so we helped ourselves to some eggs, cut a small pin hole through the shell and see who could suck out the innards the fastest. Some were even warm yet! We called it a man’s game.

One day when Alan and I were hiking we noticed a cow lying down. As we approached her we could see part of a body of an animal and its hind legs were sticking out from her behind and she was exhausted and moaning. Alan asked me to help him pull out the baby and we did. The calf’s rear side was all dried up but its front was wet and no life. We petted the cow but she just couldn’t get up and just moaned so we ran to the RCMP’s office for help. We pointed out the location where the cow was and he put us into his truck and we got there in a hurry. He looked at the cow and told us to move back and look away, so I looked. He pulled out his rifle from his truck and shot her dead. It was such a loud bang my ears were ringing for a long time. That’s the first time I saw anything like that! Before he sent us home he told us that he will contact the Aboriginal owner to haul his cow back home. That incident just won’t go away from my mind, even today. We just couldn’t understand why he did that.

Whenever we played “Hide and Go Seek” I used to pride myself as a good runner with lots of stamina but when we used to play after school, there was a girl that always came chasing me. Eventually she proved that she was faster than I was and once I kept on running way up into the hills even—far away but she relentlessly chased me but wouldn’t tag me even if I slowed down and I finally had to lay down exhausted but still she didn’t tag me and while looking me over, just laughed with a big smile. We just walked back after that but everybody had already left. I was humbled by a girl and she didn’t even brag! After Susan read this she wanted me to spell out the girl’s name. I told her—“Hey, I was only about 10 or 11 years old!” I did like her though. Thinking back, I must have run fast only if I was in “real danger.”

© 2013 Frank Maikawa