I hope this uniquely American story will serve as a reminder to all those who cherish their liberties of the very fragility of their rights against the exploding passions of their more numerous fellow citizens, and as a warning that they who say that it can never happen again are probably wrong.

—Michi Nishiura Weglyn, Years of Infamy

Among the many stories of Tule Lake, perhaps the saddest and least known is that of the approximately 5,500 Americans of Japanese descent who renounced their U.S. citizenship during World War II. At Tule Lake, 7 out of 10 citizens 18 years and older renounced, and 73% of families had at least one renunciant.

Imprisoned in the Tule Lake Segregation Center, they coped with survival in a chaotic, lawless concentration camp and prepared for an uncertain future fed by false and contradictory rumors. Those who renounced their American citizenship had no legal representation nor did they understand what they were giving up, nor did they know that, once shorn of their U.S. citizenship, they could be deported as “alien enemies.”

Most renounced in an effort to keep themselves and their families together in protective custody at the Segregation Center until the war ended. Renouncing was a way to avoid being removed once again to an uncertain future, with the war against Japan ongoing, no homes to go back to, no jobs, and no money. Many others renounced out of anger toward America’s hypocrisy and injustice and saw little hope for a future in a country that rejected and imprisoned them.

Tule Lake’s past as the Segregation Center wracked by mass renunciations has stigmatized Tuleans as “troublemakers” and “disloyals,” an anathema to the postwar Japanese American narrative that stressed loyalty and patriotism. Those who gave up their devalued U.S. citizenship felt shamed and silenced by a Japanese American community that expressed little sympathy for their plight. Also contributing to the story’s suppression was that the government records documenting it were unavailable until recent decades.

A commonly-held view attributes the mass renunciations of U.S. citizenship to pro-Japan organizations that pressured others to renounce. However, the literature describes many other factors that contributed to the thousands of renunciations. Moreover, declassified documents reveal intense strategy discussions taking place mid-1944 between military and government officials on how, once the exclusion order was rescinded, they could continue to detain Japanese Americans who were not charged with any wrongdoing. Drawing on these sources, this paper outlines the circumstances that set the stage for the mass renunciations at the Segregation Center.

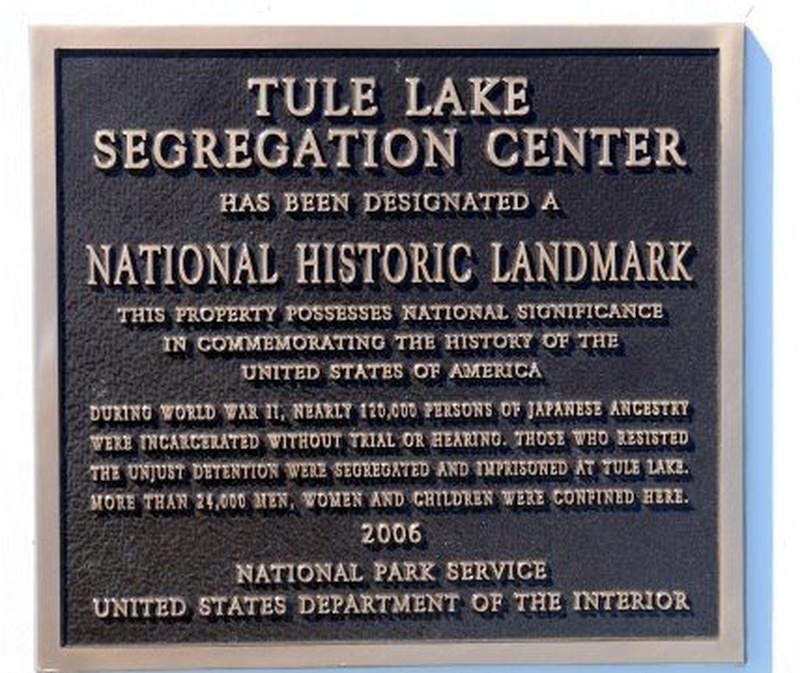

Creation of the Tule Lake Segregation Center

Tule Lake was the first of ten War Relocation Authority camps that implemented Executive Order 9066, issued February 19, 1942, requiring all persons of Japanese ancestry be removed from the West Coast. Tule Lake opened on May 26, 1942. It was the only camp to become a segregation center. It became the largest camp, with a peak population over 18,700 Nikkei. It was the only camp ruled under martial law for months by the U.S. Army. Nearly all Japanese Americans who renounced citizenship did so from Tule Lake. Because of all the turmoil and strife, it was the last camp to close, on March 28, 1946.

Tule Lake became the focal point of resistance after 12,000 Japanese Americans were shipped there from other WRA camps. The reason for this “segregation” was a negative response, a qualified response or a non-response to the infamous Loyalty Questionnaire, the source of the two questions that divided the Japanese American community into two groups, the “loyal” and the “disloyal.” Question 27 asked, “Are you willing to serve in the armed forces of the United States on combat duty, wherever ordered?” Question 28 asked, “Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States and faithfully defend the United States from any or all attack by foreign or domestic forces, and forswear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese emperor, or any other foreign government, power, or organization?”

"No-No’s"—in anger, resentment and disgust—gave negative responses to questions 27 and 28, or refused to answer them. The Japanese American Citizens League harshly condemned the "No-No’s” as troublemakers for their resistance, arguing that the war and incarceration demanded a strong showing of loyalty to America. Because Tule Lake had the highest proportion of "No-Nos" of all the camps, the WRA decided to imprison all the "disloyals” there.

On July 15, 1943, Tule Lake became the Segregation Center, a community filled with the most articulate dissident leaders and organizers from the other WRA camps. According to FBI interviews, old Tuleans said they had no idea how shabbily they were being treated until people from other camps drew comparisons with what they left.1 The Western Defense Command was also aware of the potential for conflict, noting the “considerable jockeying for political position by the newcomers, who often had been leaders of the pro-Japanese groups in the other Projects.”2

The Segregation Center became a complex, overcrowded community wracked with labor disputes, work stoppages, strikes and demands for improved living and working conditions.3 On October 7, 1943, a group of 43 workers who protested the firing of three coal workers were fired for insubordination, but skillful newcomers were able to negotiate their rehiring. The following week, a farm truck overturned and 29 workers were injured. One died. The same day, another farm group protested treatment by an Army sentry. The incidents led to a farm worker strike that began October 16th. Project Director Raymond Best retaliated against the strikers by terminating all farm workers’ jobs October 19. To undermine the protesters’ main leverage, Best brought in Nikkei inmates from other WRA camps. The strikebreakers earned $1 an hour to harvest the crops, many times more than the usual $16 per month that inmate farmworkers received.4

These events led inmates to seek representation and establish their own governing body, called the Daihyo Sha Kai, composed of two elected representatives from each block. This body selected a Negotiating Committee of seven Nikkei inmates designated to meet with Project Director Best to address concerns of the imprisoned population. They met October 26th and raised the issue of their “status as prisoners of war entitled to rights under the Geneva Convention.” The Negotiating Committee wanted community government. It wanted to settle the farm incident and to work with WRA administrators to improve living and working conditions.5

After the Daihyo Sha Kai learned that on November 1, 1943 WRA Director Dillon Myer would be visiting the Segregation Center, they requested a meeting with him to discuss improving the living and working conditions at Tule Lake. Their request was refused. Undeterred, the Daihyo Sha Kai announced to the colony that Myer would meet with the Committee and would speak to the people. Men, women, babies and young children assembled in the firebreak area near the administration building, and by 1:30 PM a crowd ranging between 5,000 to 10,000 had gathered, waiting expectantly.6

While the prisoners regarded the assembly as a peaceful gathering and were hopeful for Negotiating Committee progress in improving conditions at Tule Lake, some of the Caucasian staff evidently feared a violent demonstration or potential riot. Despite the fact many other WRA staff reported the gathering as peaceful and non-threatening, the next day, a barbed wire fence was erected, separating the Caucasian section of the camp from that of the inmate population. Project Director Best also issued an order prohibiting public gatherings of Nikkei inmates in the administration hospital, warehouse and Caucasian personnel areas.7

The seven-person Negotiating Committee, led by spokesman George Kuratomi, a “No-No” segregated from the Jerome WRA Camp to Tule Lake, eventually met with WRA Director Myer. They brought up unsatisfactory living and working conditions in the Segregation Center, including the farm workers’ termination, the use of strikebreakers, and food shortages because the administration had diverted food to the strikebreakers. They raised concerns about pay and hours worked; deficiencies in living conditions including the poor housing construction and defective plumbing; the amount of food being supplied and misappropriation of certain food items by Caucasians. They raised complaints about the Caucasian doctors and nurses, citing instances of neglect and malpractice. They expressed what would become a major concern within the Segregation Center: resegregation, or the separation of those who sought repatriation and expatriation to Japan from the “old Tuleans” who wished to remain in the U.S.8

During the meeting with Myer, Dr. Reese Pedicord, the racist Caucasian physician in charge of the Center’s medical care, was beaten up. Pedicord, who commonly referred to the Japanese American physicians, nurses and patients as “Japs” and displayed callous disregard toward their welfare, had refused a family’s pleas to send their badly burned baby to Klamath Falls for additional treatment. The baby died from the burns, and the grief-stricken father attacked Dr. Pedicord, punching and kicking him.9 However, among the Caucasian population in and around Tule Lake, this event caused an outbreak of anti-Japanese hysteria.

Three days later, on November 4, 1943, the Segregation Center was thrown into turmoil that led to the repression of the Army occupation, and the disintegration of trust between the imprisoned population and the government personnel who controlled them. That evening, a disturbance erupted when inmates saw a truck leaving the warehouse area believed to be loaded with food for the Nikkei strikebreakers housed at a nearby CCC camp. Food supplies in the segregation center were short because on the night of October 29, 1943, thirty tons of staple foods had been removed from the Project warehouse and transported to the farm barracks outside the camp to provide food for “loyal” Japanese Americans used as strikebreakers.10

Although three trucks were actually dispatched to pick up another group of Japanese American strikebreakers scheduled to arrive at Klamath Falls, the escalating turmoil, several altercations and confusion led overwrought Director Best to call in the Army. At 9:50 PM, November 4, the Army troops entered the Tule Lake Center and took over its administration.11

The military police, assisted by the WRA’s Internal Security police, arrested some 15 male inmates in the warehouse area, and singled out three suspected dissidents for a night of brutality.12 The three were detained, savagely beaten, tortured and thrown into the stockade. One of them suffered permanent mental impairment, one committed suicide, and the third, disillusioned with American justice, renounced and expatriated to Japan.13

As for the elected representatives of the Nikkei inmate population, on November 11, 1943, Lt. Col. Verne Austin, Commander of the Military Police occupying Tule Lake, told members of the Daihyo Sha Kai that he did not believe they represented the Center, rounded them up and imprisoned them in the hastily erected Army stockade.14

Notes:

1. Summary of Information, War Relocation Authority and Japanese Relocation Centers. FBI Headquarters files, August 2, 1945, pp 1-196. Declassified September 18, 1991. Page 129. RG 60, Entry 38B, WWII FBI Files 62-69030-710, Box 81, 650/230/32/38/5.

2. Supplemental Report of the Western Defense Command, Vols. I of III, Page 72. RG 499, Entry 290, Box 9, 319.1.

This report, written from the files of the Civil Affairs Division of the WDC, the office of record, covers the period November 1, 1942 to September 4, 1945, continues where the DeWitt Final Report, a misnomer, left off. It was a confidential document—developed for potential use to determine abuse of military power. The forums the Army anticipated for the report were a Congressional Claims Commission; litigation concerning the right of the military to exercise wartime controls which would require a history to the Supreme Court; and a defense of wartime powers of the military in event of potential Congressional limitations. Although the Supplemental Report was confidential, and, as stated by the WDC, was “written without consideration to how prejudicial the information might be,” the document’s unstated purpose was to explain events from the perspective of the WDC.

3. Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. Personal Justice Denied. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C., December 1982. Page 209.

4. Supplemental Report, pages 73-76. The prevailing wages for a free man at the time were $12 to $20 per day, compared to the prison wages paid to inmates of $12 a month to the unskilled and $16 to the skilled, as cited in Acheson, Secretary of State v. Murakami, et. al., 176 F. 2nd 953.

5. Supplemental Report, pages 76-77.

6. Supplemental Report, page 78.

7. Supplemental Report, page 82.

8. RG 210, Entry 48, Box 268, File 102.2. Transcript of meeting in Mr. Best’s office at 1:30 PM, November 1, 1943. Also, see Supplemental Report, page 80.

9. Supplemental Report, page 79.

10. FBI Report August 2,1945, page 122.

11. Supplemental Report, page 85.

12. Record of events, decimal file no. 323.7 Tule Lake, CAD, by Lt. Col. Verne Austin, CMP, Commanding.

13. FBI report August 2, 1945, pages 162a-d. Torture at Tule Lake, concerning the cases of Tokio Yamane, Tom Yoshio Kobayashi, and Koji Todoroki.

Willard E. Schmidt, National Director of Internal Security denied that any third degree methods had been used in questioning these Japanese, and stated that the injuries received by them had been incurred in fights incident to their arrest, and that the Japanese would not have been hurt had they not been resisting arrest. Delbert R. Cole, Chief of Internal Security at the Center, also denied that third degree methods have been practiced on these prisoners. He denied that the prisoners were mistreated or manhandled in any way, and pointed out that the Japanese were Army prisoners, inasmuch as the Army was in the process of assuming control, and that he and his staff had merely assisted the Army.

Several individuals’ recollections varied significantly from the Internal Security stories. Among them were Dr. Harry Marks of the Center’s hospital. “Dr. Marks stated he stood near the door of the room where the above Japanese was being questioned, and that he saw Mahrt [Larry Mahrt was an internal security officer and former pro baseball player] hit the Japanese with a piece of baseball bat which blow knocked the Japanese down but not out. Mahrt also proceeded to beat the Japanese with his fists, and during the whole time they were accusing this Japanese of calling various Caucasians ‘sons-of-bitches.’ After each blow at the Japanese, Mahrt would again ask, ‘Who is a son-of-a-bitch now?’ Dr. Marks stated that this procedure continued for a considerable length of time, and that Lieutenant Frank Doran of the Army stood by and watched the proceeding. ...Doran then proceeded to talk to the Japanese, who Marks said he later identified as Kobayashi, and when Kobayashi did not write the names of the various ringleaders as requested by Doran, Doran suddenly hit Kobayashi with a hard left. Marks stated he noticed that Doran did not hit the Japanese any more, and that he later observed Doran had his left hand in a cast and presumed he had broken it when he hit Kobayashi.”

Clifford Leroy Payne, was interviewed after he resigned in February 1944, and furnished a signed statement excerpted here. “The Japanese were overcome and taken to the Administration Building where they were ordered to lie down on the floor. Mr. Payne stated that they refused to do so whereupon he knocked one Jap down with his fist. Mahrt hit another Jap over the head with a baseball bat and thereafter proceeded to take about three more passes at the same Jap with the baseball bat.

“Delbert Cole then asked Kobayashi for the names of the Japanese ringleaders. Kobayashi replied that he, ‘didn’t know nothing.’ Mahrt grabbed Kobayashi by the shirt and brandished the remains of the baseball bat which he was still carrying, saying, “Talk fast.” Kobayashi again replied that he ‘didn’t know nothing.’ The M.P. Captain spoke up and said, ‘Dammit—hit him.’ Mahrt acted accordingly and hit Kobayashi over the head with the remains of the baseball bat. Kobayashi went down under the blow and laid on the floor partly unconscious. He then reached down and shook him until he regained complete consciousness whereupon he hauled him to his feet. He still refused to give any information. Mahrt then began to slap him in the face on either side and to hit him in the face and around the head with his fists. He did not hit him hard enough to knock him unconscious. By this time Kobayashi was leaning on the desk. Lieutenant Doran was on the other side of the desk and leaning forward Doran said, ‘God dammit, you’re going to talk or I’ll knock that eye right out of your head.’ Kobayashi refused to talk so Lieutenant Doran hit him a terrific right square in the eye. The blow was so hard that Lieutenant Doran broke his fist. Kobayashi went down under the blow and although he was not unconscious he refused to get up. I reached over and pulled him to his feet. Mahrt then started to slap Kobayashi on either side of the face again. He would stop the punishment at intervals and give Kobayashi an opportunity to talk and when Kobayashi refused would continue the beating. Throughout all these proceedings I had been itching to take a sock at the Jap so I shoved Mahrt aside and hit Kobayashi a hard right blow to the jaw with my fist. Kobayashi went down and out.”

Payne stated that thereafter Kobayashi was revived and was given a further beating by Officer Mahrt and was kicked in the ribs. ...The M.P. Captain then drew his gun and pointed it at Kobayashi, threatening “you’d better talk because you don’t have long to live.”

“Mr. Payne stated that to his own knowledge he did not know of any force or threats being used toward any of the other Japanese being interviewed, however, he did hear screams emanating from other rooms and assumed that they were coming from other Japanese being interviewed.”

14. Supplemental Report, page 89.

* This article was originally published in the Journal of the Shaw Historical Library, Vol. 19, 2005, Klamath Falls, OR.

* * *

* Barbara Takei will be a presenter for “The Tule Lake Segregation Center: Its History and Significance” session at JANM’s National Conference, Speaking Up! Democracy, Justice, Dignity on July 4-7, 2013 in Seattle, Washington. For more information about the conference, including how to register, visit janm.org/conference2013.

© 2005 Barbara Takei